脑损伤

-

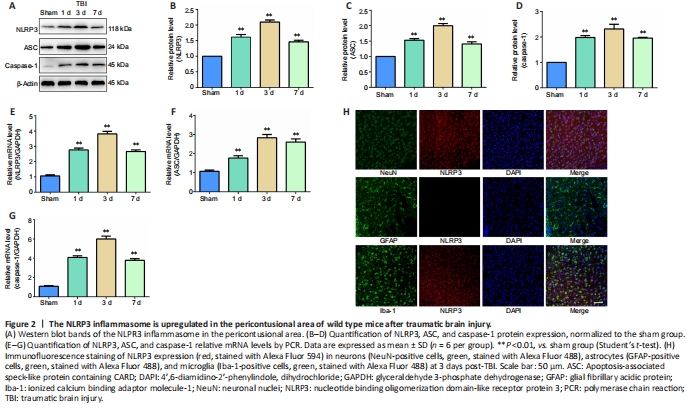

Figure 2|The NLRP3 inflammasome is upregulated in the pericontusional area of wild type mice after traumatic brain injury.

Western blot and PCR were performed to examine the NLRP3, ASC, and caspase-1 protein and mRNA levels, respectively, in pericontusional regions of WT mice at different time points post-TBI. The protein and mRNA expression levels of NLRP3, ASC, and caspase-1 all increased post-TBI; this increase peaked on day 3 and lasted at least 7 days (Figure 2A–G). Therefore, we selected WT mouse brain slices 3 days post-TBI to detect NLRP3 expression in neurons, astrocytes, and microglia using the immunofluorescence method. The results indicated that NLRP3 was expressed in neurons and microglia post-TBI (Figure 2H).

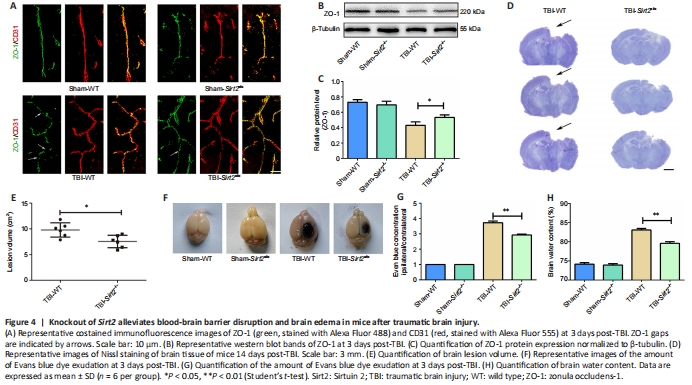

Figure 4|Knockout of Sirt2 alleviates blood-brain barrier disruption and brain edema in mice after traumatic brain injury.

TBI leads to BBB disruption. ZO-1 is a fundamental constituent of the BBB and plays a crucial role in maintaining BBB integrity (Cash and Theus, 2020). Immunostaining of brain tissues at 3 days post-TBI for ZO-1 and the vascular marker CD31 showed continuous costaining of ZO-1 and CD31 in the sham group, consistent with previous results (Xu et al., 2017b). ZO-1 gaps were present post-TBI, with fewer gaps in the TBI-Sirt2?/? group than in the TBI-WT group (Figure 4A). Meanwhile, western blot analysis revealed a much higher expression level of ZO-1 in the TBI-Sirt2?/? group than in the TBI-WT group at 3 days post-TBI (P < 0.05; Figure 4B and C).

Nissl staining was used to calculate the volume of damaged brain tissue post-TBI in mice. The TBI-Sirt2?/? group had significantly reduced volume of damaged tissue post-TBI compared with the TBI-WT group (P < 0.05; Figure 4D and E).

EB extravasation and brain water content were used to estimate BBB integrity post-TBI. Sirt2?/? mice had significantly decreased EB leakage in the ipsilateral cortex 3 days post-TBI compared with the WT mice post-TBI, indicating that BBB disruption induced by TBI was attenuated by knockout of Sirt2 (P < 0.01; Figure 4F and G). The dry-wet weight results showed that the water content of the injured hemisphere increased post-TBI, and Sirt2?/? mice had significantly reduced brain water content compared with the WT mice post-TBI (P < 0.01; Figure 4H).

Figure 5|Knockout of Sirt2 reduces the expression of the NLRP3 inflammasome and nerve cell pyroptosis after traumatic brain injury in vivo.

Western blot and PCR were used to detect the protein and mRNA expression levels, respectively, of each component in the NLRP3 inflammasome on day 3 post-TBI. The protein expression levels of NLRP3, ASC, and caspase-1 were increased in WT mice post-TBI compared with the sham-treated mice. The protein expression levels of NLRP3, ASC, and caspase-1 were significantly decreased in the Sirt2?/? mice at 3 days post-TBI compared with the WT mice (all P < 0.05; Figure 5A–F). The protein expression levels were consistent with the mRNA levels (Figure 5G–I).

Neuroinflammation is mediated by inflammatory cells and the cytokines secreted by the inflammatory cells (O’Brien et al., 2020). We used PCR to detect the mRNA expression levels of IL-1β and IL-18 in the brain tissue around the lesion 3 days post-TBI, and we used ELISA to detect the protein expression levels of IL-1β in blood 3 days post-TBI. The PCR results showed that Sirt2?/? mice had significantly reduced IL-1β and IL-18 mRNA levels post-TBI compared with WT mice (P < 0.01; Figure 5J). ELISA results also showed that Sirt2?/? mice had significantly reduced secretion of IL-1β in the blood compared with WT mice (P < 0.01; Figure 5K).

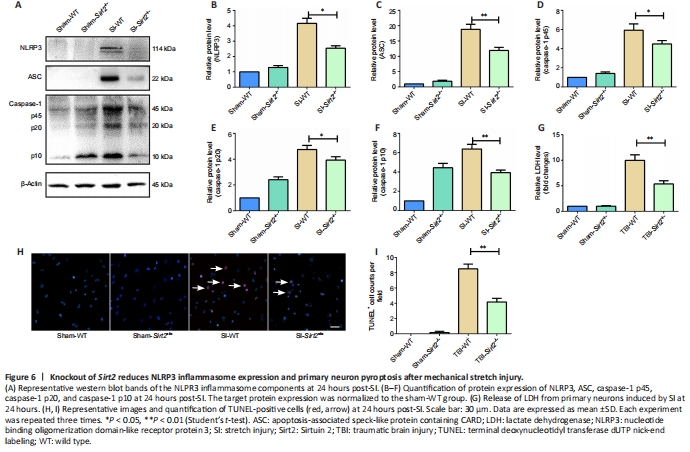

Caspase-1 is an effector of the NLRP3 inflammasome, and caspase-1 activity determines the inflammatory response mediated by the NLRP3 inflammasome (Miao et al., 2011). We found that caspase-1 activity was significantly elevated in the brain tissues post-TBI, and its activity was increased less in Sirt2?/? mice than in WT mice on day 3 post-TBI (P < 0.01; Figure 5L). We used TUNEL staining to detect DNA damage in nerve cells of brain tissue at 3 days post-TBI. The results showed very few TUNEL-positive cells in the sham group, but many TUNEL-positive cells were present 3 days post-TBI. Furthermore, Sirt2?/? mice had significantly reduced numbers of TUNEL-positive cells compared with WT mice post-TBI (P < 0.01; Figure 5M and N).Figure 6|Knockout of Sirt2 reduces NLRP3 inflammasome expression and primary neuron pyroptosis after mechanical stretch injury.

We used primary cultured neurons to investigate the underlying mechanism of Sirt2 knockout post-SI in vitro. Western blot analysis showed that the protein expression levels of NLRP3 (P < 0.05), ASC (P < 0.01), and caspase-1 (P < 0.01) were significantly decreased in the SI-Sirt2?/? group compared with those in the SI-WT group (Figure 6A–F), which were similar to our in vivo results.

LDH release tests are used to assess cell membrane integrity. Cytoplasmic LDH is released into the culture medium when the cell membrane integrity is compromised (Jing et al., 2020). Compared with the control group without intervention, LDH dramatically increased after SI, while knockout of Sirt2 reduced the release of LDH from primary neurons induced by SI (P < 0.01; Figure 6G). The numbers of TUNEL-positive primary neuron cells were significantly reduced in the SI-Sirt2?/? group compared with those in the SI-WT group (P < 0.01; Figure 6H and I).