脑损伤

-

Figure 1|Acute or chronic social interaction activates LS GABA neurons.

To determine whether LS neuronal activity was related to social activity, we administered a home cage social interaction task (Figure 1A). This task reflected a social experience in a familiar environment (Kim et al., 2019). At 30 minutes after an acute social interaction (2 hours), we measured the number of neurons in the LS labeled with neuronal activity biomarker c-Fos-immunoreactive proteins. We found that the number of c-Fos-positive neurons in the LS of mice interacting with a new target mouse was significantly higher than that of mice that did not interact with a new target mouse (t(8) = 4.0720, P = 0.0036; Figure 1B). This finding indicates that LS neuronal activity is involved in acute social interaction. Given that lateral septal neurons are predominantly GABAergic neurons (more than 90%) (Zhao et al., 2013), we conducted double immunofluorescence histochemistry to determine whether the c-Fos-positive neurons were co-localized with GABAergic neurons. In mice interacting with or without a target mouse, co-localization with LS GABAergic neurons was observed for most c-Fos-positive neurons (91.5 ± 1.3% and 90.8 ± 1.2%), with no obvious difference between the groups (t(10) = 0.4118, P = 0.6892; Figure 1C). This finding indicates that LS GABAergic neuronal activity might be critically involved in social interaction. We performed an electrophysiological assay to confirm the spontaneous firing of GABAergic neurons after an acute social interaction. The recording results revealed that, compared with the control mice, those with a target exhibited an increased frequency of action potentials (P = 0.0349; Mann-Whitney U test). However, the action potential amplitude (P = 0.2584; Mann-Whitney U test) and membrane potential (unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction, P = 0.6208) remained constant (Figure 1D).

We further confirmed the association between GABAergic neuronal activity and social interaction by conducting a chronic home cage social interaction task. In this task, mice interacted with a social target mouse in their home cage for 30 minutes per day on five consecutive days (Figure 1E). At 30 minutes after the end of the last social interaction task, we conducted immunofluorescence detection of ΔFosB, an indicator of neuronal activity that can be induced by various stimuli, and is frequently used in chronic stress/experience paradigms (Nestler, 2015; Wang et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2021). Specifically, we measured the number of ΔFosB-immunoreactive neurons in the mice LS. We found that social interaction-treated mice had an increased number of ΔFosB-positive neurons in the LS (t(6) = 2.8770, P = 0.0282; Additional Figure 1A). We then estimated the percentage of ΔFosB-positive GABAergic neurons among the total number of ΔFosB-positive neurons. Consistent with the results of the acute social interaction task, in mice that interacted with a social target mouse, the majority of ΔFosB-positive neurons in the LS showed co-localization with GABAergic neurons (91.48 ± 2.36%). This value was nearly the same in mice without a social target mouse (90.85 ± 1.23%) (t(4) = 0.2368, P = 0.8244; Additional Figure 1B). The electrophysiological results also validated the social treatment-related hyperexcitability of GABAergic neurons, which was characterized by an increased number of action potentials (two-tailed unpaired t-test with Welch′s correction, P < 0.0010), decreased membrane potential (t(31) = 9.9110, P < 0.0010), and no change in the action potential amplitude (t(31) = 0.3143, P = 0.7554) of LS GABAergic neurons in mice interacting with a social target mouse compared with that in mice that did not interact with target mice (Figure 1F).

Figure 2| Inhibition of LS GABA neurons suppressed social behaviors.

To investigate how LS GABAergic neuronal activity affects social interaction behaviors, we used Vgat-Cre mice that expressed Cre recombinase in inhibitory GABAergic neuronal cell bodies in many brain regions including the LS, without changes in the expression of endogenous vesicular inhibitory amino acid transporters (Vong et al., 2011). We then bilaterally administered an AAV that expressed Cre-dependent hM4D(Gi) (designated AAV-hM4), as well as a control (mCherry virus, designated as AAV-mCherry) into the LS of Vgat-Cre mice. Three weeks after this treatment, we intraperitoneally injected the mice with CNO to inhibit the activity of LS GABAergic neurons. We then performed the three-chamber test to examine social preference and social novelty behaviors 45 minutes following CNO administration (Figure 2A). During the social preference phase, we found that AAV-hM4-injected mice spent significantly less time exploring the stranger-1 chamber (P = 0.0134), while the amount of time spent exploring the middle chamber (P = 0.6764) and the object chamber remained the same (P = 0.1508) (treatment: F(1, 13) = 0.0001, P > 0.9999; social squares: F(2, 26) = 23.7400, P < 0.0010; interactions: F(2, 26) = 4.7080, P = 0.0180). Furthermore, the AAV-hM4-injected mice showed a significantly lower social interaction index than the control mice (AAV-mCherry) (t(13) = 2.7940, P = 0.0152). Furthermore, the AAV-hM4-administered mice spent less time sniffing the stranger-1 mouse (P < 0.0010), but not the object (P = 0.9885) (treatment: F(1, 13) = 32.8800, P < 0.0010; social squares: F(1, 13) = 120.6000, P < 0.0010; interactions: F(1, 13) = 45.9900, P < 0.0010), and had a significantly lower discrimination index than the control mice (two-tailed unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction, P = 0.0106; Figure 2B). These results demonstrate that social preference abilities were impaired after LS GABAergic neurons were inhibited.

During the social novelty phase, the AAV-hM4-injected mice spent less time exploring the stranger-2 chamber (P = 0.0079). However, we did not observe a significant difference in the duration of time spent in the middle (P = 0.1924) or familiar mouse (stranger-1) chamber (P = 0.4639) (treatment: F(1, 13) = 0.0001, P > 0.9999; social squares: F(2, 26) = 30.4000, P < 0.0010; interactions: F(2, 26) = 5.2080, P = 0.0125). The AAV-hM4 group had a significantly lower social interaction index than the control group (P = 0.0358; two-tailed unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction). Additionally, the AAV-hM4-administered mice spent less time sniffing the new mouse (stranger-2) (P < 0.0010) versus the familiar mouse (stranger-1) (P = 0.4590) (treatment: F(1, 13) = 9.4930, P = 0.0088; social squares: F(1, 13) = 76.010, P < 0.0010; interactions: F(1, 13) = 53.7300, P < 0.0010). The AAV-hM4 group had a significantly lower discrimination index than the control mice (P = 0.0289; Mann-Whitney U test) (Figure 2C). Social behavior impairment did not appear to be caused by an alteration in anxiety or locomotion, because AAV-hM4 treatment did not affect the amount of time spent in the centre of the open field test (t(13) = 1.6900, P = 0.1149; Additional Figure 2A) or the distance travelled in the locomotor test (treatment: F(1, 13) = 0.6951, P = 0.4195; timepoints: F(14, 182) = 20.1200, P < 0.0010; interactions: F(14, 182) = 0.5086, P = 0.9262; total distance: t(13) = 0.8337, P = 0.4195; Additional Figure 2B). Therefore, LS GABAergic neuron inhibition attenuated sociability as well as social novelty behavior in mice. Hence, we validated the efficiency of hM4D in mediating neural inhibitory activity. We used a 30-minute restraint paradigm to increase basal neural activity, and estimated c-Fos-positive cell numbers 45 min after the CNO injection. AAV-hM4 mice showed a dramatic decrease in the number of c-Fos-positive cells in the LS compared with the control mice (t(4) = 4.4270, P = 0.0115; Figure 2D). Furthermore, according to our electrophysiological results, the AAV-hM4 group showed a decrease in action potential frequency (unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction, P = 0.0012) and no change in action potential amplitude (t(19) = 0.7755, P = 0.4476) compared with the control group (Figure 2E).

Figure 3| The activation of LS GABA neurons increases social behaviors.

Next, we explored how LS GABAergic neuronal activation influences social interaction behaviors by bilaterally injecting an AAV expressing Cre-dependent hM3D (Gq) (designated as AAV-hM3) or mCherry virus (designated as AAV-mCherry) as a control into the LS of Vgat-Cre mice. CNO was intraperitoneally injected 3 weeks afterwards, thereby activating GABAergic neurons in the LS. At 45 minutes after the injection, we assessed social behaviors via the three-chamber test (Figure 3A). In the social preference phase, AAV-hM3-injected mice exhibited no remarkable differences in the amount of time taken to explore the stranger-1 chamber (P = 0.9998), middle chamber (P = 0.9979), or object chamber (P = 0.7705) (treatment: F(1, 14) = 0.7656, P = 0.3963; social squares: F(2, 28) = 37.4200, P < 0.0010; interactions: F(2, 28) = 0.2340, P = 0.7929). The social interaction index of the AAV-hM3 group did not differ from that of the control group (AAV-mCherry) (t(14) = 0.9639, P = 0.3515). We observed AAV-hM3-injected mice showing an increase in the amount of time taken to sniff the stranger-1 mouse (P = 0.0091), but not the object (P = 0.9854) (treatment: F(1, 14) = 4.5750, P = 0.0506; social squares: F(1, 14) = 40.8600, P < 0.0010; interactions: F(1, 14) = 4.9310, P = 0.0434), AAV-hM3-injected mice exhibited a significantly higher discrimination index than the control group (P = 0.0164; Mann-Whitney U test; Figure 3B). Thus, activated LS GABAergic neurons appear to promote social preference behaviors.

In the social novelty phase, the time spent by the AAV-hM3-treated mice to explore the new mouse (stranger-2) (P = 0.2715), middle (P = 0.8408), and familiar mouse (stranger-1) chambers (P = 0.0572) was identical to that in the control mice (treatment: F(1, 14) = 0.0001, P > 0.9999; social squares: F(2, 28) = 9.4150, P < 0.0010; interactions: F(2, 28) = 3.0970, P = 0.0609), although the AAV-hM3-treated mice showed a prominently higher social interaction index than the control mice (t(14) = 2.7930, P = 0.0144). Additionally, the AAV-hM3-treated mice spent more time sniffing a new stranger-2 mouse (P < 0.0010), but not a familiar stranger-1 mouse (P = 0.4245) (treatment: F(1, 14) = 11.9500, P = 0.0039; social squares: F(1, 14) = 74.7000, P < 0.0010; interactions: F(1, 14) = 35.9800, P < 0.0010) compared with the control mice, and had a significantly higher discrimination index than the control mice (t(14) = 6.1210, P < 0.0010; Figure 3C). Finally, we tested anxiety and locomotor activity. As with the open field test, the AAV-hM3-treated mice exhibited no alterations in the amount of time spent in the arena center (t(14) = 0.0734, P = 0.9426; Additional Figure 2C), or the distance travelled in the locomotor test (treatment: F(1, 14) = 2.9700, P = 0.1068; timepoints: F(14, 196) = 16.9100, P < 0.0010; interactions: F(14, 196) = 0.7406, P = 0.7317; total distance: t(14) = 1.7230, P = 0.1068; Additional Figure 2D). Thus, LS GABAergic neuron activation appears to enhance preference as well as social novelty behaviors in mice. Furthermore, we measured the efficiency of hM3, which mediates neural stimulating activity, and found that the number of c-Fos-positive cells in the AAV-hM3 mice LS was significantly higher than that in the control group (unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction, P = 0.0410; Figure 3D). Moreover, in comparison with the control group, the action potential frequency (t(20) = 6.3800, P < 0.0010) was augmented and the action potential amplitude remained unaltered (unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction, P = 0.5952) in the AAV-hM3 group (Figure 3E).

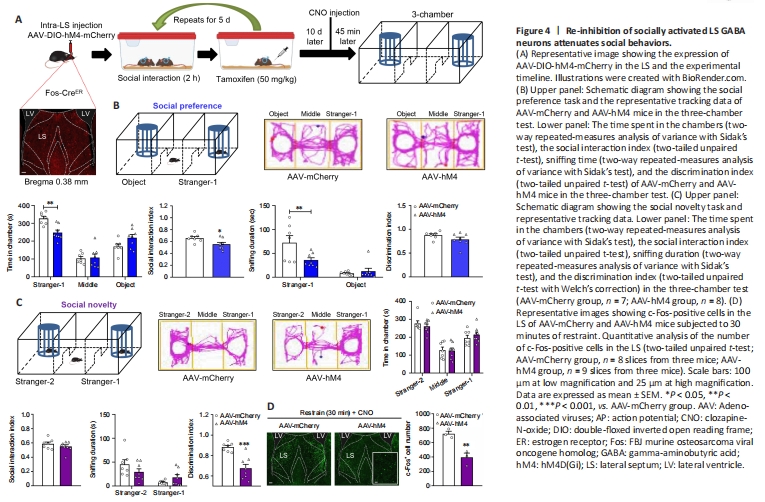

Figure 4|Re-inhibition of socially activated LS GABA neurons attenuates social behaviors.

Next, we examined the effect of specifically modulating social experience-activated LS GABA neurons on social behaviors. Fos-CreERT2 transgenic mice were used for this purpose. The CreERT2 fusion protein comprises Cre recombinase, which is fused to the human estrogen receptor with a triple mutant form. This protein is restricted to the cytoplasm, because it does not attach to 17β-estradiol (its natural ligand) at physiological concentrations and enters the nuclear compartment after binding to tamoxifen, a synthetic estrogen receptor ligand (Guenthner et al., 2013). In our experimental design, we bilaterally administered an AAV that expressed Cre-dependent hM4D(Gi) (designated as AAV-hM4) as well as control mCherry virus (designated as AAV-mCherry) into Fos-CreERT2 mice LS. At 3 weeks after treatment, these mice were subjected to the chronic social experience paradigm. Tamoxifen was then intraperitoneally injected to induce Cre activity by promoting its transport to the nucleus, and we conducted the three-chamber test 45 minutes following CNO administration (Figure 4A). We found that the Cre-dependent hM4D(Gi) virus was expressed exclusively in the LS, which indicates that the social experience-activated LS GABA neurons were successfully labeled (Figure 4A).

In the social preference phase, compared with the control mice (AAV-mCherry), the AAV-hM4-injected mice spent much less time exploring the stranger-1 chamber (P = 0.0030), and roughly the same amount of time exploring the middle chamber (P = 0.9941) and object chamber (P = 0.0976) (treatment: F(1, 13) = 2.0220, P = 0.1786; social squares: F(2, 26) = 47.7200, P < 0.0010; interactions: F(2, 26) = 6.1310, P = 0.0066), and the AAV-hM4-injected mice showed a markedly decreased social interaction index (t(13) = 2.4680, P = 0.0282). Furthermore, compared with the control mice, AAV-hM4-injected mice spent less time sniffing the stranger-1 (P = 0.0078), but not the object (P = 0.9114) (treatment: F(1, 13) = 3.2920, P = 0.0927; social squares: F(1, 13) = 35.2600, P < 0.0010; interactions: F(1, 13) = 7.6590, P = 0.0160). Moreover, the AAV-hM4-injected mice did not show obvious differences in the discrimination index when compared with the control mice (t(13) = 1.5590, P = 0.1429; Figure 4B). Thus, social preference appears to have been impaired following the re-inhibition of social experience-activated LS GABAergic neurons.

Next, during the social novelty phase, we observed similar changes in the time spent by the AAV-hM4-injected mice in exploring the stranger-2 chamber (P = 0.8521), middle chamber (P = 0.9984), and familiar mouse chamber (P = 0.7697) (treatment: F(1, 13) = 0.0001; P > 0.9999; social squares: F(2, 26) = 29.5700, P < 0.0010; interactions: F(2, 26) = 0.4388, P = 0.6495). The social interaction index of the AAV-hM4-injected mice also remained unchanged in comparison with that of the control group (t(13) = 1.0040, P = 0.3335; Figure 4C). Furthermore, we found no differences in the time spent by the AAV-hM4-injected mice in sniffing the new stranger-2 mouse (P = 0.1862) or the familiar stranger-1 mouse (P = 0.4917) (treatment: F(1, 13) = 0.1295, P = 0.7248; social squares: F(1, 13) = 29.9700, P < 0.0010; interactions: F(1, 13) = 8.3920, P = 0.0125) when compared with the control mice. However, the AAV-hM4-injected mice had a significantly lower discrimination index compared with the control mice (unpaired t-test with Welch’s correction, P < 0.0010; Figure 4C).

In the open field test, we found no group differences in the time spent in arena’s center (t(13) = 1.2120, P = 0.2472; Additional Figure 3A) or the distance traveled in the locomotor test (treatment: F(1, 13) = 1.7690, P = 0.2064; timepoints: F(14, 182) = 22.8900, P < 0.0010; interactions: F(14, 182) = 1.2540, P = 0.2405; total distance: two-tailed unpaired t-test with Welch′s correction, P = 0.2408; Additional Figure 3B). We also measured the efficiency of hM4 in mediating neural inhibitory activity. We used a 30-minute restraint paradigm to increase basal neural activity, and measured the number of c-Fos-positive cells 45 minutes after the CNO injection. AAV-hM4 mice showed a dramatic reduction in c-Fos-positive cells in the LS compared with control mice (t(4) = 4.7540, P = 0.0089; Figure 4D).

Figure 5|Social behaviors are enhanced by re-activating socially activated LS GABA neurons.

We further assessed the effect of specifically re-activating the social experience-activated LS GABA neurons on social behaviors. According to the re-inhibition procedure, we injected an AAV expressing Cre-dependent hM3D(Gq) (designated as AAV-hM3) as well as mCherry virus as a control (designated as AAV-mCherry) into the Fos-CreERT2 mice LS. After 3 weeks, we conducted a test using a chronic social experience paradigm. Cre activity was induced by intraperitoneally injecting tamoxifen. We conducted the three-chamber test 45 minutes following CNO administration (Figure 5A). The Cre-dependent hM3D(Gq) virus was expressed in the LS, indicating that LS GABA neuron activation was modulated by social experience (Figure 5A). AAV-hM3-treated mice displayed no alterations in the amount of time spent in the stranger-1 chamber (P = 0.2346), middle chamber (P = 0.9726), or object chamber (P = 0.1078) (treatment: F(1, 13) = 0.0001, P > 0.9999; social squares: F(2, 26) = 132.9000, P < 0.0010; interactions: F(2, 26) = 2.6390, P = 0.0905; Figure 5B) or the social interaction index compared with the control mice (AAV-mCherry) (t(13) = 1.3900, P = 0.1877) in the social preference phase. Furthermore, compared with the control mice, AAV-hM3-injected mice spent more time sniffing the stranger-1 (P < 0.0010), but not the object (P = 0.9257) (treatment: F(1, 13) = 14.0100, P = 0.0025; social squares: F(1, 13) = 220.7000, P < 0.0010; interactions: F(1, 13) = 24.0700, P < 0.0010). The AAV-hM3-treated mice had a significantly elevated discrimination index compared with the control mice (t(13) = 4.2730, P < 0.0010; Figure 5B).

Compared with the control mice, the test mice showed similar alterations in the amount of time taken to explore the stranger-2 chamber (P = 0.9225), middle chamber (P = 0.7853), and familiar mouse chamber (P = 0.9893) (treatment: F(1, 13) = 0.0001, P > 0.9999; social squares: F(2, 26) = 35.2200, P < 0.0010; interactions: F(2, 26) = 0.3739, P = 0.6917). Furthermore, the social interaction index did not significantly differ between the AAV-hM3-injected group and the control group (Mann-Whitney test, P = 0.9551) in the social novelty phase (Figure 5C). However, the AAV-hM3-injected mice spent more time sniffing the new stranger-2 mouse (P < 0.0010) but not the familiar stranger-1 mouse (P = 0.8014) (treatment: F(1, 13) = 8.5130, P = 0.0120; social squares: F(1, 13) = 70.0700, P < 0.0010; interactions: F(1, 13) = 8.4050, P = 0.0124), and showed an increased discrimination index (P = 0.0059; Mann-Whitney U test) compared with the control mice (Figure 5C). Thus, the reactivated LS GABAergic neurons appear to have promoted social novelty.

The open field test data revealed no difference in the amount of time spent in the arena’s center (P = 0.2810; Mann-Whitney U test; Additional Figure 3C) and the distance traveled in the locomotor test (treatment: F(1, 13) = 0.1184, P = 0.7363; timepoints: F(14, 182) = 38.3100, P < 0.0010; interactions: F(14, 182) = 1.3760, P = 0.1685; total distance: P = 0.6126; Mann-Whitney U test; Additional Figure 3D) between the two groups, suggesting the absence of anxious behaviors. The hM3-mediated neural activity was efficient, because the c-Fos-positive cell number was substantially higher in the AAV-hM3 mice LS than in the control mice at 45 minutes following CNO administration (t(4) = 4.0250, P = 0.0158; Figure 5D).

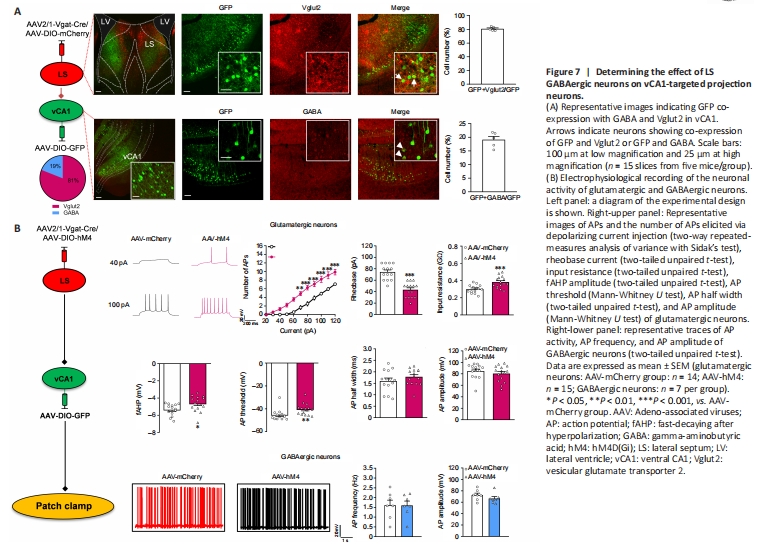

Figure 7|Determining the effect of LS GABAergic neurons on vCA1-targeted projection neurons.

We confirmed that LS GABA neuron activation enhances social behaviors and confirmed the effect of LS-vCA1 projection on social behavior. We then analyzed the neural types of LS synaptic targeted neurons in vCA1 using the monosynaptic and anterograde AAV2/1-Vgat-Cre virus and immunofluorescence co-localization analysis (Figure 7A). We injected a mixture of AAV2/1-Vgat-Cre and AAV-DIO-mCherry into the LS, and AAV-DIO-GFP into vCA1, and 3 weeks later found that the mCherry labeled neurons in the LS were co-labeled with GABA (97.52 ± 1.21%). This supports the specificity of AAV2/1-Vgat-Cre in GABAergic neurons (Additional Figure 7A and B). LS synaptic targeted neurons in the vCA1 were co-localized with both glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons (80.93 ± 1.25% and 19.07 ± 1.24%, respectively). We further determined whether the LS GABAergic neurons regulated the activity of these two types of targeting neurons. The patch clamp test results showed increased neural activity of glutamatergic targeted neurons following the inhibition of LS GABAergic neurons, with more action potentials elicited by the same amount of current injection (treatment: F(1, 27) = 25.8900, P < 0.0010; current: F(12, 324) = 206.3000, P < 0.0010; interactions: F(12, 324) = 11.3700, P < 0.0010), lower rheobase current (t(27) = 6.3290, P < 0.0010), higher input resistance (t(27) = 3.7670, P < 0.0010), and lower hyperpolarization amplitude (t(27) =2.3550, P = 0.0260) and action potential threshold (P = 0.0019; Mann-Whitney U test) than the control group (Figure 7B). Other membrane properties, including the action potential half width (t(27) = 1.1720, P = 0.2514) and amplitude of action potentials (P = 0.3942; Mann-Whitney U test) were not significantly different between these groups (Figure 7B). Furthermore, both groups showed no changes in action potential frequency (t(12) = 0.0239, P = 0.9813) or action potential amplitude (t(12) = 1.1840, P = 0.2593) for GABAergic neurons (Figure 7B).