周围神经损伤

-

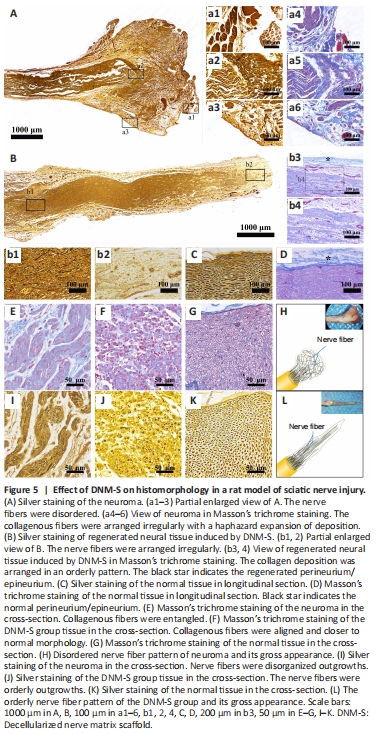

Figure 5|Effect of DNM-S on histomorphology in a rat model of sciatic nerve injury.

Silver and Masson’s trichrome staining showed that nerve fibers in the control group were disordered and arranged irregularly (Figure 5A and a1–3), along with a haphazard expansion of collagen deposition (Figure 5A and a4–6) at 8 weeks. Immediately after neurotomy, the alignment of nerve fibers and collagen deposition were interrupted (Additional Figure 1A). With muscle fiber invasion, the histopathological morphology of the nerve end transformed into traumatic neuroma (Additional Figure 1B). DNM-S provided structural guidance and biological barriers, such as the endoneurium and perineurium, for regenerating neural tissue (Figure 5B and b1–4, Additional Figure 1C and D). The collagen deposition and regenerative nerve fibers were arranged in an orderly pattern in the DNM-S group, similar to the normal nerve (Figure 5C and D). It is worth noting that the perineurium/epineurium of the DNM-S gradually incorporates to create a physical barrier to the nerve end (Figure 5b3), similar to the perineurium/epineurium of the normal nerve (Figure 5D; black star). In the cross section, the spatial pattern of collagen deposition and regenerative nerve fibers was entangled and disorganized outgrowths in the control group (neuroma) compared with the DNM-S group and normal nerve tissue (Figure 5E–L). In short, the ECM construction of nerve stumps was remodeled by the implanted DNM-S (Additional Figure 1E and F), which subsequently transformed the regenerative pattern of nerve fibers (Figure 5H and L).

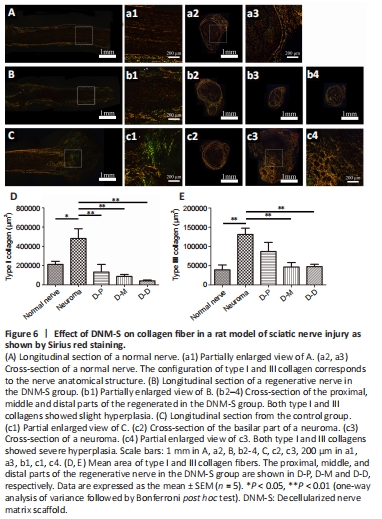

Figure 6|Effect of DNM-S on collagen fiber in a rat model of sciatic nerve injury as shown by Sirius red staining.

Sirius red staining was utilized to evaluate collagen formation and distribution by polarized light microscopy (Figure 6). The results showed that two types of collagens coexisted in normal nerves (Figure 6A and a1–a3), regenerating neural tissue in DNM-S (Figure 6B and b1) and neuromas (Figure 6C and c1–c4). In the longitudinal section, the DNM-S group showed slight type dysplasia compared with the normal nerve group (Figure 5a1 and b1). Similar to normal nerve (Figure 5A and a2–a3), type I collagen-positive area of perineurium/epineurium was greater than that of endoneurium area in the DNM-S group (Figure 6b2–b4). Nevertheless, both type I and III collagen showed obvious hyperplasia in the basilar part of the neuroma (Figure 6c1 and c2) and neuroma (Figure 6c3 and c4). Type I collagen positive area in neuroma was significantly greater than that in the proximal, middle and distal parts of DNM-S (P < 0.01; Figure 6D). The mean area of type III collagen in the proximal, middle and distal parts of the DNM-S group were significantly less than that in the control group at 8 weeks after surgery (P < 0.01; Figure 6E).

Figure 7|Effect of DNM-S on the vascular malformation and α-SMA expression in a rat model of sciatic nerve injury.

Vascular and muscular invasion was assessed by Masson’s trichrome staining, muscle staining and immunohistochemistry for α-SMA (Figure 7). There was no obvious vascular invasion in the basis part of neuroma in the control group (Figure 7A and a1–3), however, the large-sized, distorted, and proliferated blood vessels appeared in neuromas (Figure 7B, b1–3, C, and c1–3). Muscle staining demonstrated the presence of muscular invasion in the neuroma while it was not observed in the middle part of the implanted DNM-Ss (Figure 7B and Additional Figure 2), suggesting that DNM-Ss possess a physical barrier structure to avoid the surrounding vascular and muscular invasion. α-SMA was expressed in myofibroblasts and blood vessels in the control group (Figure 7D and d1–d3), while it was mainly expressed in vascular wall in the DNM-S group (Figure 7E and e1–e3). In the DNM-S group, moderate vascularization resulted in vascular smooth muscle proliferation and α-SMA was mainly expressed in vascular wall (Figure 7F–H, and f–h). α-SMA-positive area in the proximal, middle and distal parts of the DNM-S was lower than that in the neuroma in the control group at 8 weeks after surgery (Figure 7I).

Figure 8|Effect of DNM-S on the myelinated axons in cross-sections in a rat sciatic nerve injury model at 8 weeks post-surgery under Toluidine blue staining.

At 8 weeks after surgery, the histomorphometry of axons and the area of axon regeneration at the different portions of the harvested tissue were quantified. Compared to the axons on the uninjured side (Figure 8A), the perineurium structure and a small number of nerve bundles were regenerated in the implanted DNM-S (Figure 8B). As the regeneration distance increased, fewer and fewer axons were observed in the implanted DNM-S, and no axons were observed in the distal region (Figure 8C and D). The outgrowth of regenerated axons reached outside of the perineurium in both the DNM-S and control groups (Figure 8C and E), suggesting that some axons would escape from the anastomosis. The outgrown axons in the neuroma were disordered and twisted (Figure 8F, f1, and f2). The middle and distal parts of DNM-S contained significantly fewer axonal regions than the neuroma in the control group (P < 0.05; Figure 8G). The axes of the abnormal axons in the neuroma were longer than those of the proximal parts of the DNM-S (P < 0.01; Figure 8H). DNM-S seemed to have an obvious effect on the inhibition of axon outgrowth outside the perineurium, although the difference between the two groups was not statistically significant (Figure 8I).

Figure 9|Effect of DNM-S on the regenerated axons in a rat model of sciatic nerve injury at 8 weeks after surgery as shown by TEM.

On TEM images, we found that in addition to the morphologically deformed myelinated fibers compared with the normal nerve (Figure 9A and a), there was also a mass of morphologically deformed unmyelinated fibers growing in the traumatic neuroma (Figure 9B and b). Consistent with the axon morphology, the ECM fiber configuration differed markedly between the DNM-S (Figure 9C and c) and the neuroma (Figure 9D and d). In the implanted DNM-S, the unmyelinated fibers were in the protective barrier of the perineurium (Figure 9E and e; blue arrows and green pseudocolor), which was absent in the neuroma. In the distal part of DNM-S, no myelinated or unmyelinated fibers were observed among the regenerated tissue (Figure 9F and f).