神经退行性病

-

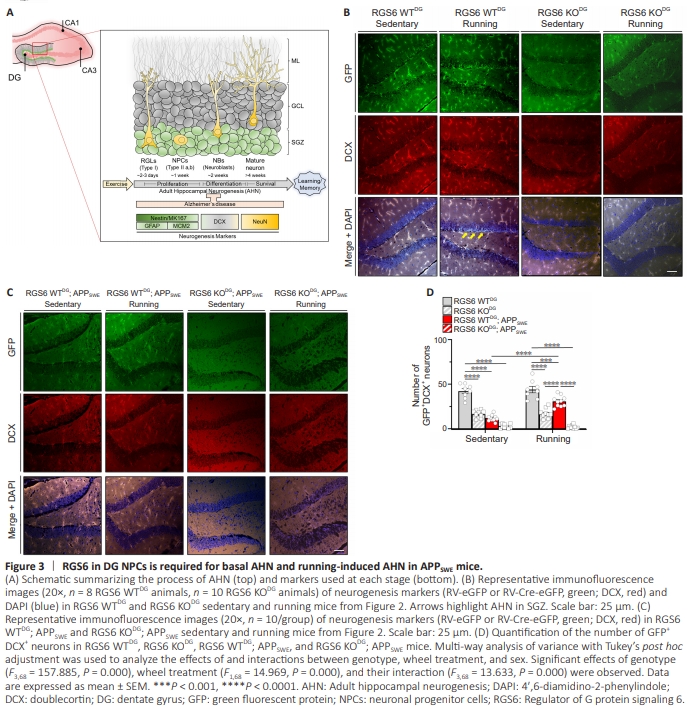

Figure 3 | RGS6 in DG NPCs is required for basal AHN and running-induced AHN in APPSWE mice.

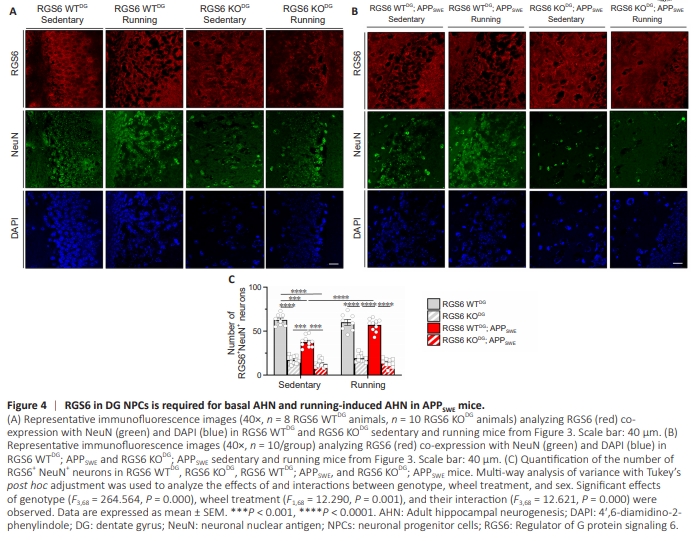

Figure 4 | RGS6 in DG NPCs is required for basal AHN and running-induced AHN in APPSWE mice.

Given our behavioral evidence that RGS6 is required for running-induced reversal of cognitive dysfunction in APPSWE mice, we evaluated the role of RGS6 in DG NPCs in AHN, whichis reduced in AD in humans and amyloid mouse models of AD. We performed immunohistochemical analyses of the number of eGFP- (derived from RV-infected NPCs), doublecortin (DCX)- and neuronal nuclear antigen (NeuN)-positive neurons (Figure 3A) in hippocampal sections of the mice used for behavioral studies above. As shown in Figure 2A, this analysis was performed 13 weeks following the injection of RV-Cre-eGFP or RV-eGFP into the DG of 20-week-old mice. Zhao et al. (2006) characterized the sequelae of AHN in mice by studying GFP expression within the DG at various times following RV-eGFP injection into the DG as performed in our studies. At early times post injection (3–7 days), GFP+ cells were localized in the SGZ, with the labeling of these progenitors persisting until the latest time point (14 months). GFP+ dendrites growing into the molecular layer were present at ~14 days which underwent growth and extensive arborization like that of mature neurons by 8 weeks. At this time point, GFP labeling of cells/neurons was seen in the SGZ, molecular layer, and hilus with more GFP+ labeling in running vs control mice. Figure 3B shows representative images of AHN in RGS6 WTDG and RGS6 KODG mice under sedentary and voluntary running conditions. Quantification of AHN occurring in the SGZ region of these mice as well as their APPSWE counterparts (Figure 3C) is shown in Figure 3D. First, we found that eGFP and DCX immunoreactivity were strongly co-localized in neurons within the DG of RGS6 WTDG mice (Figure 3B), identifying these as adult-born neurons derived from DG NPCs (Figure 3A). As shown, there is robust AHN present in the SGZ (shown by arrows) as well as in the molecular layer and hilus. Dendrites appear as lines or curves in these single confocal plane images when not completely within the confocal plane. Second, RGS6 KODG mice showed a significant decrease in AHN compared with RGS6 WT mice (Figure 3B, P < 0.0001). Third, voluntary running did not increase AHN in either RGS6 WTDG or RGS6 KODG mice groups (Figure 3B). Figure 3C shows representative images of AHN in RGS6 WTDG; APPSWE and RGS6 KODG; APPSWE mice. Though we again observed evidence of AHN shown by co-localization of eGFP and DCX immunoreactivity in these mice, sedentary RGS6 WTDG; APPSWE mice showed significantly reduced AHN compared with their non-APPSWE counterparts (Figure 3B–D, P < 0.001). Second, voluntary running significantly increased the number of these adult-born neurons in RGS6 WTDG; APPSWE mice as compared with sedentary RGS6 WTDG; APPSWE mice (Figure 3B–D, P < 0.0001). Third, RGS6 deletion from DG NPCs significantly impaired AHN in both sedentary and running RGS6 WTDG; APPSWE mice (Figure 3B–D). We next compared the number of NeuN positive (NeuN+ ) neurons in the DG granule cell layer of RGS6 WTDG and RGS6 KODG mice and their APPSWE counterparts under sedentary and voluntary running conditions. Again, these mice were approximately 7.5 months old at the time of this analysis. Representative images of RGS6 positive (RGS6+ ) and NeuN+ neurons in the DG granule cell layer of these mice are shown in Figure 4A and B with quantification of the number of RGS6+ NeuN+ neurons in the granule cell layer in Figure 4C. First, we found that RGS6 was highly expressed in the membrane region of NeuN+ neurons in the granule cell layer of the DG in RGS6 WTDG mice. Second, RGS6 KODG mice showed a significant decrease in the number of these neurons compared with RGS6 WTDG mice (Figure 4C, P < 0.0001). Third, voluntary running did not increase the number of these neurons in either RGS6 WTDG or RGS6 KODG mice groups (Figure 4C). Fourth, sedentary RGS6 WTDG; APPSWE mice had reduced numbers of RGS6+ NeuN+ neurons compared with sedentary RGS6 WTDG mice, and this reduction was rescued by voluntary running (Figure 4A–C, P < 0.001). Finally, RGS6 deletion from the DG of APPSWE mice, like their non-APPSWE counterparts, led to a dramatic loss in the number of RGS6+ NeuN+ neurons that was not rescued by voluntary running in these mice (Figure 4A–C). Together, these results show that running-induced cognitive improvements in APPSWE mice are accompanied by increases in AHN and adult born neurons that are dependent upon RGS6 expression in DG NPCs. There was a similar correlation between AHN and learning and memory in RGS6 WTDG mice where we observed no effects of running on cognition or AHN but where RGS6 deletion from DG NPCs caused loss of both cognition (Figure 2B–D) and AHN (Figure 3B–3D and 4A–4C). These findings show that RGS6 is necessary for basal and voluntary running-induced AHN in APPSWE mice.

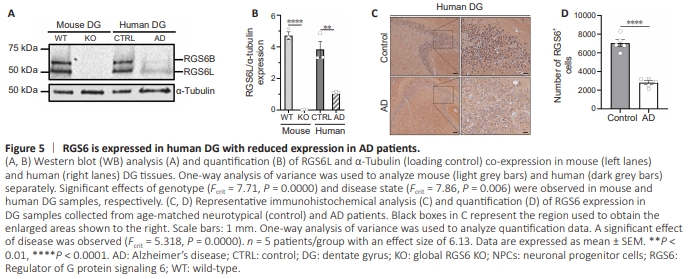

Figure 5 | RGS6 is expressed in human DG with reduced expression in AD patients.

In our initial report of cloning multiple splice forms of RGS6, we generated a peptide antibody specific for long N-terminal forms of RGS6 (RGS6L). We used this antibody to show that RGS6 is robustly expressed in neurons within the CA1, CA3, and DG regions of the mouse hippocampus (Stewart et al., 2014). The process of AHN generates new granule cells in the DG that mature and extend their dendrites into the molecular layer and axons to the CA3 region. Given the recent finding that RGS6L mediates voluntary wheel running-induced AHN in mice (Gao et al., 2020) and the link between exercise and cognitive improvements in AD patients (Erickson et al., 2011; Yu et al., 2021), we examined the expression of RGS6L in the human DG. Figure 5A shows that human DG expresses the same major RGS6 isoforms seen in mice that are absent in the hippocampus of RGS6 global knockout mice. As we recently described (Ahlers-Dannen et al., 2022), the lower 56 kDa band represents RGS6L isoforms and the larger 69 kDa band represents a novel brain-specific form of RGS6 (RGS6B) that contains the N-terminal sequence our antibody was generated against. There is a marked loss in RGS6L expression in the DG of AD patients (Figure 5A and B). Immunohistochemical analysis further demonstrates that RGS6 is expressed in neurons within the DG of humans with significant loss of these RGS6+ neurons in AD patients (Figure 5C and D). Unfortunately, autofluorescence precluded our ability to examine RGS6 expression in human SGZ using markers for NPCs or NBs (Figure 3A). Therefore, while the function of RGS6 in human DG is not clear, its loss in AD is consistent with the well-known loss of hippocampal neurons and the impairment in AHN that occurs in AD (Figure 3A).