神经退行性病

-

Figure 2 | The effect of D30 on Aβ deposition and neuroinflammation in mice that received intraventricular injection of fAβ.

To better understand the effects of D30 on cognitive function, we assessed changes in pathological indicators associated with AD progression, including Aβ deposition, oxidative stress, and neuroinflammation. Immunohistochemical analysis showed that fAβ injection into the lateral ventricles led to Aβ deposition in the hippocampus and cortex. The D30 treatment groups exhibited less Aβ deposition than the fAβ group (Figure 2A). Additionally, ELISA analysis showed that intraventricular fAβ injection increased cortical Aβ deposition, and this was reversed by D30 treatment, consistent with the immunohistochemical results (Figure 2B). In addition, ELISA analysis indicated that fAβ injection increased reactive oxygen species levels and decreased superoxide dismutase levels in the cortex, whereas treatment with D30 restored both to normal levels (Figure 2C and D). Activated microglia and astrocytes secrete inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and IL-1β, and exhibit increased expression iNOS, all of which promote neuroinflammation and neuronal death (Wang et al., 2023b). Activated microglia exhibit upregulated expression of Iba1, a microglial marker, and activated astrocytes exhibit increased GFAP expression (Escartin et al., 2021). Given the role of neuroinflammation in AD progression, we next assessed the levels of inflammatory indicators in the different groups. ELISA analysis demonstrated that fAβ injection led to upregulation of IL-1, IL-6, Iba1, and GFAP in the cortex, whereas treatment with D30 counteracted this effect (Figure 2E–H). Furthermore, immunoblotting confirmed that fAβ injection increased Iba1, GFAP, and iNOS expression and decreased expression of the neuronal marker NeuN in the hippocampus. These effects were significantly reversed by treatment with D30 at all tested doses, indicating that D30 protects against inflammatory damage in fAβ-injected mice (Figure 2I–M). Thus, the 20 mg/kg dose was selected for further in vivo experiments employing D30.

Figure 3 | D30 reduces Aβ deposition and suppresses microglial activation in the hippocampus of mice subjected to lateral ventricular fAβ injection.

Neuroinflammation induced by Aβ deposition and glial cell activation is closely associated with AD. Therefore, inhibiting Aβ deposition and maintaining glial cell homeostasis are important strategies for treating AD (Gao et al., 2022a). To investigate the effect of D30 on fAβ-induced neuroinflammation and glial cell activation, mice were injected with fAβ and then treated once daily with D30 for 1 week. The mice were then sacrificed to assess the 1-week timepoint or subjected to an additional fAβ injection followed by once-daily D30 administration for another week before being sacrificed to assess the 2-week timepoint (Figure 3A). As shown in Figure 3B and C, a single fAβ injection resulted in Aβ deposition, and a second fAβ injection led to an outbreak of Aβ in the hippocampus. D30 treatment effectively reduced the Aβ deposition induced by both one and two injections of fAβ. Injecting fAβ into the lateral ventricle led to microglial activation, as evidenced by characteristic morphological changes such as enlargement of the cell body and branch retraction in the hippocampal dentate gyrus regions. In contrast, D30 treatment suppressed fAβ-induced microglial activation.Notably, two injections of fAβ not only induced deposition of a large amount of Aβ, but also promoted more significant changes to microglial morphology. We confirmed that microglial activation correlated positively with the amount of Aβ deposition. Quantitative analysis showed that D30 effectively reduced fAβ deposition at both the 1-week (P < 0.05; Figure 3D) and 2-week (P < 0.05; Figure 3G) timepoints. Immunoblotting confirmed that D30 effectively reduced Aβ deposition in the hippocampus after two fAβ injections (P < 0.0001; Figure 3J and K). In addition, D30 suppressed the fAβ-induced morphological changes in microglia, namely the reduction in the number and length of the branches, at the 1-week (P < 0.05; Figure 3E and F) and 2-week (P < 0.01; Figure 3H and I) timepoints, as quantified by skeleton and Sholl analyses.

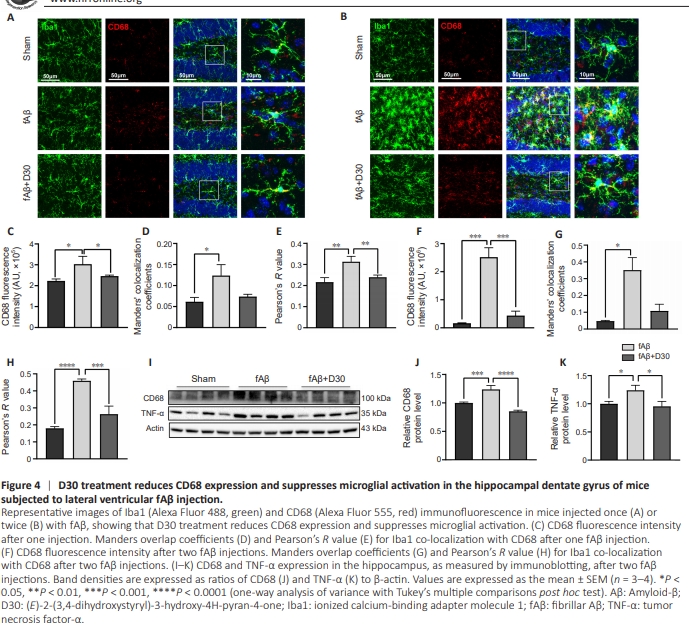

Figure 4 | D30 treatment reduces CD68 expression and suppresses microglial activation in the hippocampal dentate gyrus of mice subjected to lateral ventricular fAβ injection.

CNS that, when activated, release inflammatory cytokines that can cause inflammatory injury. Activated proinflammatory microglia are referred to as M1 microglia. In contrast to activated M1 microglia, activated M2 microglia protect neighboring cells and promote tissue repair by releasing anti-inflammatory cytokines (Wang et al., 2023a). Inhibiting microglial overactivation and inflammation can effectively reduce neuroinflammation and mitigate AD progression. Thus, maintaining the balance of M1- and M2-polarized microglia is a potential therapeutic option for AD. Immunofluorescence showed that, when mice were injected with fAβ, microglia underwent changes in morphology and adopted the neurotoxic M1 phenotype, accompanied by a significant increase in CD68 expression in the hippocampus (Figure 4A). D30 treatment counteracted both the remodeling of microglial morphology and the increase of CD68 expression. D30 not only reduced CD68 expression (P < 0.05; Figure 4C) but also reduced the CD68 co-localization with Iba1 induced by a single fAβ injection (Figure 4D and E). The second injection of fAβ resulted in a surge in the number of microglia and a dramatic change in their morphology, accompanied by a significant increase in CD68 expression. D30 counteracted the fAβ-induced microglial activation and concomitant increase in CD68 expression and preventedalteration of microglial morphology in the hippocampal dentate gyrus (Figure 4B). Quantitative fluorescence analysis confirmed that two injections with fAβ induced CD68 expression and microglial activation more strongly than a single fAβ injection. Treatment with D30 suppressed the microglial activation induced by two fAβ injections (Figure 4F–H). Furthermore, immunoblotting showed that two injections with fAβ resulted in significant increase in the expression of the inflammatory markers CD68 (P < 0.0001, Figure 4I) and TNF-α (P < 0.05; Figure 4K), an effect that was blocked by D30 treatment (Figure 4I–K).

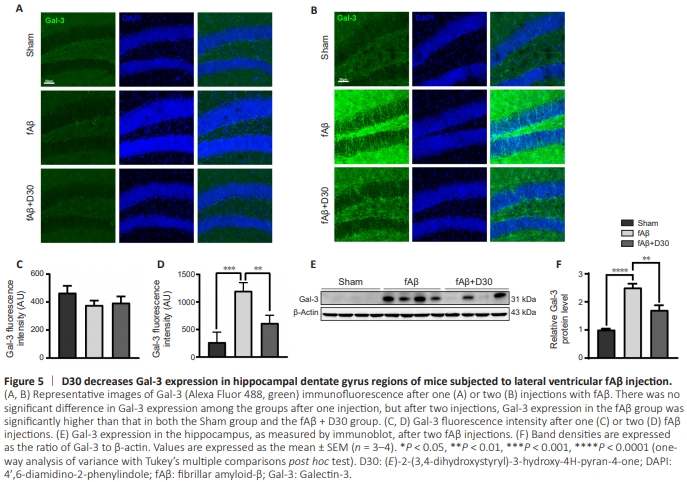

Figure 5 | D30 decreases Gal-3 expression in hippocampal dentate gyrus regions of mice subjected to lateral ventricular fAβ injection.

To address these questions, we measured Gal-3 expression in mice injected with fAβ injection and treated with D30 or left untreated. Immunofluorescence staining showed that a single fAβ injection did not increase Gal-3 expression in the mouse dentate gyrus (Figure 5A and C). Interestingly, a second fAβ injection did increases Gal-3 expression, which suggests that the induction of Gal-3 expression by fAβ was dose-dependent. Unsurprisingly, D30 treatment effectively counteracted the fAβ-induced increase in Gal-3 expression (Figure 5B). Fluorescence quantification showed that Gal-3 expression was increased in mice injected with fAβ compared with the Sham group, and this effect was reversed by treatment with D30 (Figure 5D). In addition, immunoblotting confirmed that two injections with fAβ resulted in a sharp increase in Gal-3 expression that was reversed by D30 treatment (P < 0.01; Figure 5E and F).

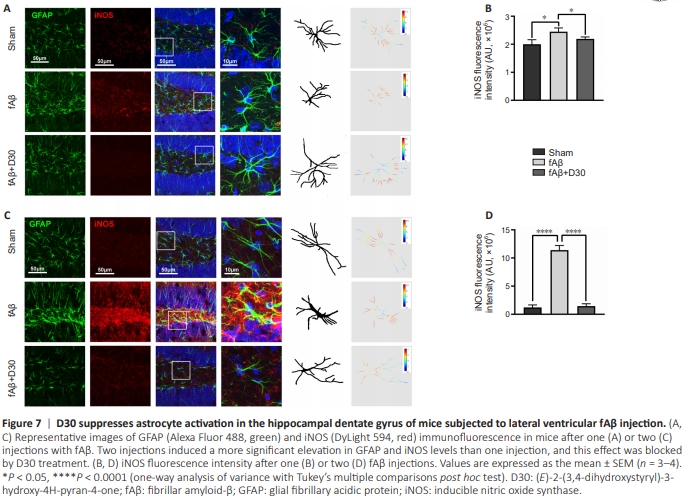

Figure 7|D30 suppresses astrocyte activation in the hippocampal dentate gyrus of mice subjected to lateral ventricular fAβ injection.

Similar to microglial activation, aberrant astrocyte activation is strongly associated with AD progression. In response to Aβ stimulation, glial cell activation is accompanied by an increase in iNOS levels (Liu et al., 2022; Yan et al., 2023). Thus, glial cell activation creates a vicious cycle that accelerates the Aβmediated inflammatory response. We found that injecting mice with fAβ increased iNOS expression in the hippocampal dentate gyrus (Figure 7A). In addition, fAβ injection altered astrocyte morphology, as reflected by thickening of the astrocytic GFAP skeleton, whereas D30 alleviated these effects. Fluorescence quantification showed that D30 suppressed the fAβ-induced increase in iNOS expression (P < 0.05; Figure 7B). We observed a robust increase in iNOS expression accompanied by more pronounced astrocyte activation in response to the second fAβ injection, and D30 nearly completely inhibited the increased in iNOS expression induced by fAβ injection. Moreover, treatment with D30 restored astrocyte morphology to that seen in the Sham group, with much less GFAP skeleton thickening, even in mice that had received two fAβ injections (P < 0.0001; Figure 7C and D)

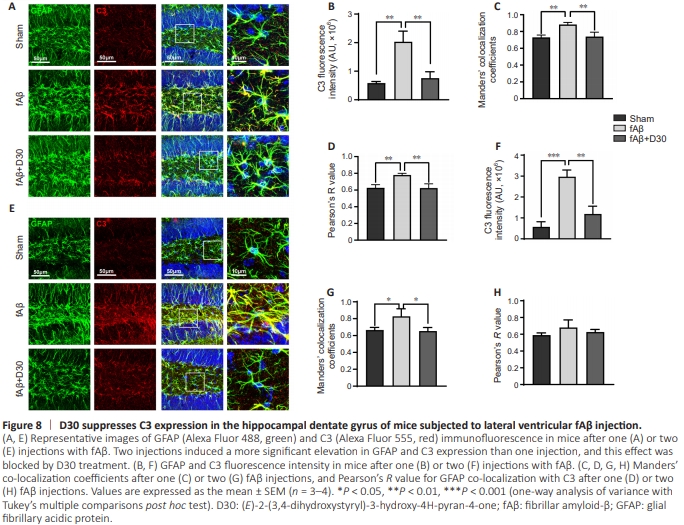

Figure 8 | D30 suppresses C3 expression in the hippocampal dentate gyrus of mice subjected to lateral ventricular fAβ injection.

In addition to the changes seen in the GFAP skeleton, fAβ injection induced C3 expression in astrocytes, an effect that was suppressed by D30 treatment (Figure 8A). Fluorescence quantification showed that D30 treatment reversed the fAβinduced increase in C3 expression, as well as the increase in GFAP co-localization with C3 (P < 0.01; Figure 8B–D), which suggest that D30 strongly prevented proinflammatory astrocyte activation. Even when two fAβ injections were administered, D30 effectively suppressed astrocyte activation and the increase in C3 expression (Figure 8E and F). The Manders overlap coefficients for co-localization of GFAP with C3 were significantly reduced by treatment with D30 (P < 0.05; Figure 8G), whereas there was no significant difference in Pearson’s R values (Figure 8H). Collectively, these results suggest that Aβ induces iNOS production, astrocytic morphological changes, and elevated C3 expression, whereas D30 treatment almost completely suppressed all of these characteristics of astrocyte activation.

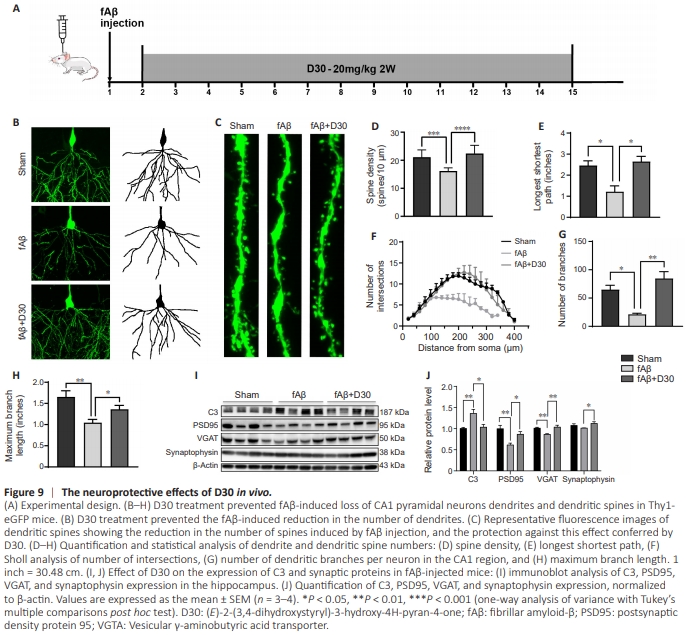

Figure 9 | The neuroprotective effects of D30 in vivo.

D30 treatment reversed fAβ-induced activation of microglia and astrocytes. In particular, in mice injected with fAβ, treatment with D30 restored the expression of CD68 and C3, markers of M1 microglia and A1 astrocytes, respectively, to levels near those seen in the Sham group. M1 microglia and A1 astrocytes are neurotoxic and destructive to synapses (He et al., 2022; Hwang et al., 2022). Thus, we expected D30 to protect against the neurotoxic effects of fAβ. To investigate this, we assessed the effect of D30 on fAβ-induced neuronal damage. Thy1.1 GFP mice were used to investigate changes in neuronal processes and dendritic spines. Lateral ventricle injections of fAβ led to neuronal damage as reflected by the reduction of dendritic spines; D30 maintained the number of neuronal branches and spines (Figure 9A–C). By quantitative analysis, D30 reversed the reduction of branches and spines induced by fAβ, implying a neuroprotective role of D30 (P < 0.05; Figure 9D–H). We next investigated the effect of D30 on the expression levels of complement and synaptic proteins, including PSD95, VGAT (vesicular γ-aminobutyric acid [GABA] transporter), and synaptophysin, in ICR mice injected with fAβ. Immunoblotting confirmed that fAβ injection increased C3 expression, whereas treatment with D30 reversed this effect. Moreover, fAβ injection decreased PSD95 and VGAT expression, whereas D30 treatment restored PSD95 and VGAT expression levels, suggesting a neuroprotective effect (P < 0.05; Figure 9I and J). GABA is a major neurotransmitter in the CNS, and VGAT is a marker for GABA transporter (Ju and Tam, 2022; de Ceglia et al., 2023), whereas PSD95 is linked to glutamatergic neurotransmission; thus, the fact that D30 treatment reversed the fAβ-induced reduction in VGAT and PSD95 expression suggests that this compound protected both glutamatergic and GABAergic synapses.