神经退行性病

-

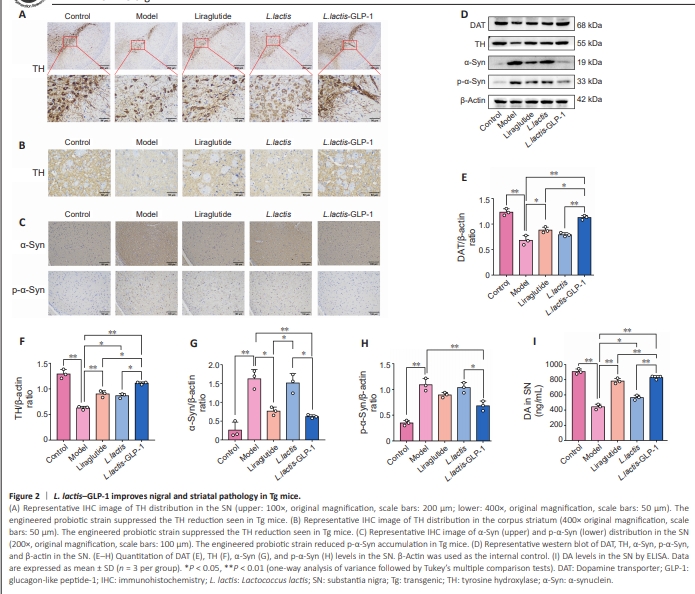

Figure 2 | L. lactis–GLP-1 improves nigral and striatal pathology in Tg mice.

Next, the distribution of DAergic neurons and the formation of Lewy bodies in the SNpc of the Tg mice was investigated by staining for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and α-Syn, respectively, to further evaluated the therapeutic effects of L. lactis–GLP-1. IHC analysis of the SN and striatum (Figure 2A and B) showed that TH expression was significantly decreased in the Tg mice, while treatment with L. lactis–GLP-1 effectively restored TH expression. Immunohistochemistry (Figure 2C) also showed that α-Syn and p-α-Syn accumulated in Tg mice, and that the engineered bacteria effectively reduced the expression levels of these proteins. Next performed western blotting of the PD pathological markers DAT, TH, α-Syn, and p-α-Syn (Figure 2D–H) and ELISA for DA (Figure 2I) in brain tissue to confirm the presence of pathological changes. The results were consistent with the pathological findings: the Tg mice showed lower DAT (P < 0.01), TH (P < 0.01), and DA (P < 0.01) levels and greater accumulation of α-Syn (P < 0.01) and p-α-Syn (P < 0.01) than WT mice (Figure 2I). WT L. lactis had a slight positive effect on Tg mice by elevating TH (P < 0.05) and DA levels (P < 0.05) (Figure 2F and I). Interestingly, though liraglutide elevated cerebral DAT (P < 0.01), TH (P < 0.01), and DA (P < 0.01) levels, the engineered probiotic strain L. lactis–GLP-1 exerted a much more prominent therapeutic effect than liraglutide on DAT (P < 0.05), TH (P < 0.05), and DA (P < 0.01) levels (Figure 2E, F and I). Furthermore, liraglutide only resulted in decreased α-Syn (P < 0.05), not p-α-Syn, levels, while L. lactis–GLP-1 treatment decreased the levels of both α-Syn and its phosphorylated form (both P < 0.01), and wild type L. lactis showed no effect on α-Syn and p-α-Syn levels (Figure 2G and H).

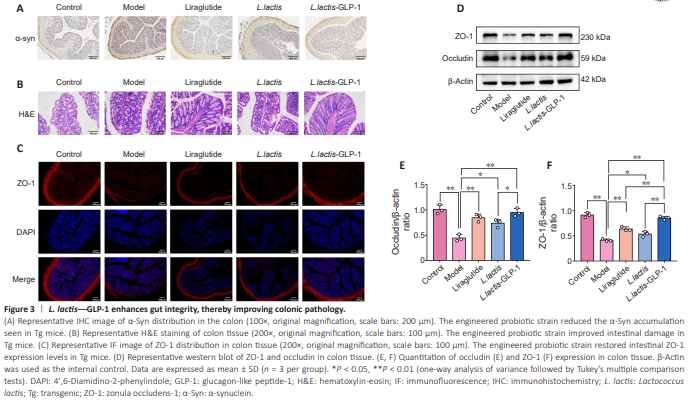

Figure 3 | L. lactis––GLP-1 enhances gut integrity, thereby improving colonic pathology.

Studies have shown that synucleinopathy in the intestine is closely related to the production and accumulation of abnormal α-Syn in the brain, and that abnormal α-Syn deposition occurs in the intestinal mucosal environment (Kim et al., 2019). Therefore, colonic pathology was assessed by H&E staining and α-Syn immunohistochemistry. Intestinal lesions, characterized by inflammatory infiltration and damaged mucosal layer integrity, in Tg mice were accompanied by α-Syn accumulation. These effects were rescued byliraglutide and L. lactis–GLP-1, and not by L. lactis. In addition, liraglutide and L. lactis–GLP-1 inhibited abnormal α-Syn expression in the gut of Tg mice and improved intestinal integrity, but L. lactis alone had no effect on α-Syn in the gut of Tg mice, proving that formation of the intestinal lesions is mediated by α-Syn accumulation. To evaluate the colonic barrier integrity, distribution of intestinal barrier molecule ZO-1 (Figure 3A–C) was determined. The findings suggested that weakening of the intestinal barrier in Tg mice could be improved by wild type L. lactis and L. lactis–GLP-1. L. lactis improved ZO-1 activity to a similar degree as liraglutide, but both were inferior to L. lactis– GLP-1. To further verify the pathological findings, western blotting (Figure 3D–F) was performed to compare the expression levels of major intestinal permeability proteins (ZO-1 and occludin) in the experimental animals. The results were consistent with the pathological findings: the Tg mice exhibited dramatically lower ZO-1 (P < 0.01) and occludin (P < 0.01) expression levels compared with WT mice (Figure 3E and F). Furthermore, both ZO-1 and occludin expression levels were increased by treating the Tg mice with liraglutide (both P < 0.01) or L. lactis (both P < 0.05). Additionally, GLP-1 and L. lactis seemed to have synergic effects on promoting ZO-1 and occludin expression (L. lactis–GLP-1 vs. liraglutide and L. lactis–GLP-1 vs. L. lactis, both P < 0.01).

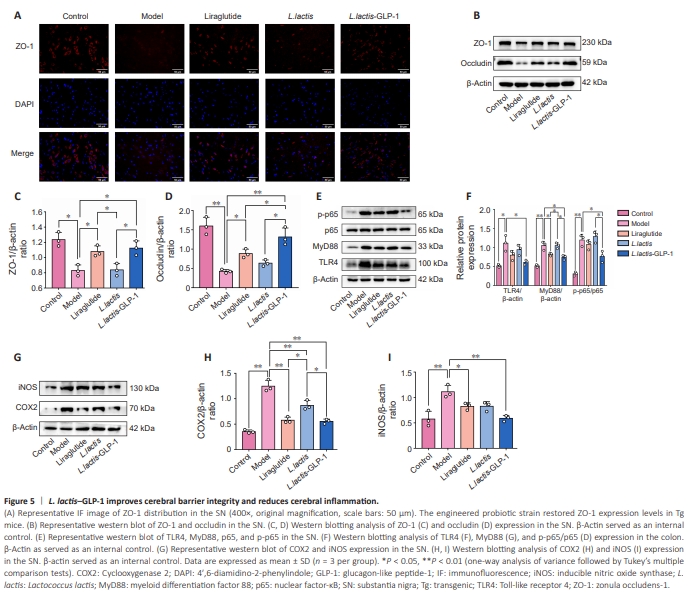

Figure 5 | L. lactis–GLP-1 improves cerebral barrier integrity and reduces cerebral inflammation.

Since our earlier results showed that synucleinopathy is accompanied by inflammation and barrier defectiveness in intestinal tract, cerebral barrier integrity and inflammation were further assessed. Immunofluorescence staining (Figure 5A) showed that ZO-1–expressing cells are depleted in Tg mice compared with WT mice. Both exogenous GLP-1 liraglutide and L. lactis– GLP-1 rescued ZO-1–expressing cells, while WT L. lactis had no overt effect. Similarly, western blotting (Figure 5B–D) demonstrated downregulation of ZO-1 (P < 0.05) and occludin (P < 0.01) expression in Tg mice compared with WT mice. Liraglutide and L. lactis–GLP-1 had similar effects on ZO-1 expression (both P < 0.05). The liraglutide-induced upregulation of occludin (P < 0.05) expression in Tg mice, however, was relatively lower than that induced by L. lactis–GLP-1 (L. lactis–GLP-1 vs. liraglutide, P < 0.05). Next, the expression levels of components of the inflammatory signaling pathway TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB (Figure 5E and F) and the inflammationassociated biomarkers COX2 and iNOS (Figure 5G–I) in brain tissue were analyzed by western blotting. The Tg mice showed elevated TLR4 (P < 0.05), MyD88 (P < 0.01), p65 (P < 0.01), COX2 (P < 0.01), and iNOS (P < 0.01) levels compared with WT mice. Surprisingly, liraglutide only had a slight effect on MyD88 (P < 0.05) expression in Tg mice but had a more pronounced effect on COX2 (P < 0.01) and iNOS (P < 0.05) expression levels. WT L. lactis did not have any effect on the expression of TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway components but downregulated COX2 expression (P < 0.01). More importantly, L. lactis–GLP-1 exerted strong anti-inflammatory effect in the cerebrum by suppressing TLR4 (P < 0.05), MyD88 (P < 0.01), p65 (P < 0.05), COX2 (P < 0.01), and iNOS (P < 0.01) expression levels.

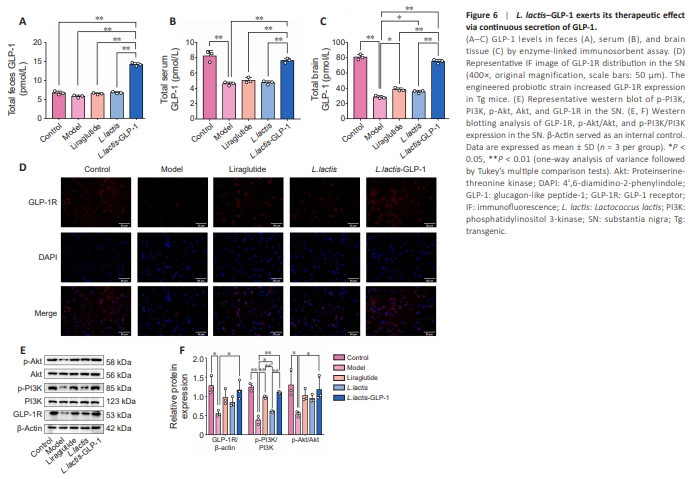

Figure 6 | L. lactis–GLP-1 exerts its therapeutic effect via continuous secretion of GLP-1.

Since a previous study showed that improvement of parkinsonism traits in Tg mice is largely GLP-1–mediated (Yue et al., 2022), next we assessed the distribution of GLP-1 in our experimental animals. ELISA (Figure 6A–C) showed no difference in fecal GLP-1 levels between WT mice and Tg mice, but the GLP-1 levels in the serum (P < 0.01) and brain (P < 0.01) of WT mice were significantly higher than those in Tg mice. Notably, L. lactis had no effect on fecal, serum, or brain GLP-1 levels, and intraperitoneal injection of the GLP-1 analog liraglutide also had no effect on fecal or serum GLP-1 levels, although brain GLP-1 levels were slightly increased (P < 0.05). However, the engineered probiotic strain L. lactis–GLP-1 significantly increased fecal (P < 0.01), serum (P < 0.01) and brain (P < 0.01) GLP-1 levels to levels comparable to those seen in normal mice.Next, distribution of the GLP-1 receptor (GLP-1R) was explored by immunofluorescence (Figure 6D). GLP-1R expression was reduced in the SN of Tg mice, while the engineered probiotic strain and the exogenous GLP-1R agonist partially rescued GLP-1R activity. To confirm the pathological findings, we performed western blotting of GLP-1R and the phosphorylated forms of its downstream signaling molecules PI3K and Akt in brain tissue (Figure 6E and F). WT L. lactis had no effect on GLP-1R, pPI3K, or p-Akt levels, and liraglutide only potentiated PI3K phosphorylation (P < 0.05), while L. lactis–GLP-1 increased GLP-1R (P < 0.01), p-PI3K (P < 0.01), and p-Akt (P < 0.05) levels, suggesting that GLP-1R activation and phosphorylation of its downstream factors are intracerebral GLP-1 concentration–dependent.

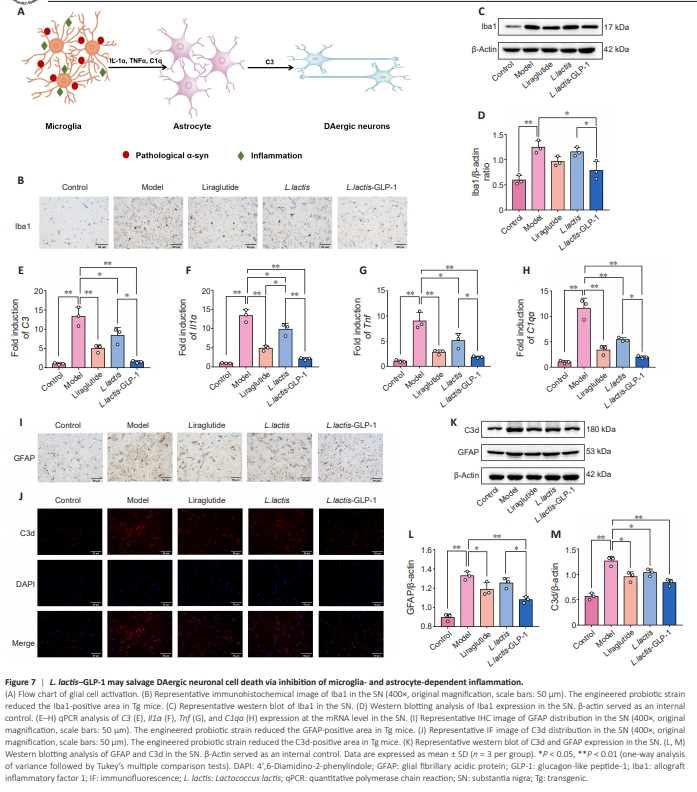

Figure 7 | L. lactis–GLP-1 may salvage DAergic neuronal cell death via inhibition of microglia- and astrocyte-dependent inflammation.

Our earlier results (Figure 7A) and previous studies have shown that synucleinopathy and inflammation activate microglia to stimulate astrocytes, which potentiate PD progression (Yun et al., 2018). Therefore, we investigated the role of microglia-mediated astrocyte activation and the subsequent impact on DAergic cells. Immunohistochemistry analysis of the microglial marker Iba1 suggested that the number of microglia is massively increased in the SNpc of Tg mice compared with WT mice, while liraglutide and L. lactis–GLP-1 reduced the number of microglia in Tg mice (Figure 7B). Semiquantitative analysis of Iba1 expression via western blotting confirmed that Iba1 expression was substantially increased in the SNpc, and only L. lactis–GLP-1 reduced this overexpression in Tg mice (Figure 7C and D). In addition, qPCR analysis (Figure 7E and F) suggested that, in Tg mice, the microglial and astrocytic inflammation–related genes Il1α, Tnf, C1qa, and C3 were overexpressed at the mRNA level compared with WT mice (all P < 0.01). Though L. lactis and liraglutide downregulated Il1α, Tnf, C1qa, and C3 mRNA to varying degrees, L. lactis–GLP-1 exhibited greater inhibition of microglial and astrocytic inflammation. Molecular localization (Figure 7I and J) and quantification (Figure 7K–M) of the inflammatory markers GFAP and C3d validated the aforementioned finding, as the number of GFAP- and C3dpositive cells and GFAP and C3d concentrations were much higher in Tg mice than in WT mice, and these effects were partially reversed by treatment with L. lactis, liraglutide, or L. lactis–GLP-1. Notably, though liraglutide decreased C3d (P < 0.05) expression, L. lactis had a greater effect on both GFAP (P < 0.05) and C3d (P < 0.05) expression levels. Hence the anti-inflammatory effects of the engineered probiotic strain L. lactis–GLP-1 appear to be primarily due to the carrier bacterium L. lactis, rather than the GLP-1 that it expresses.