周围神经损伤

-

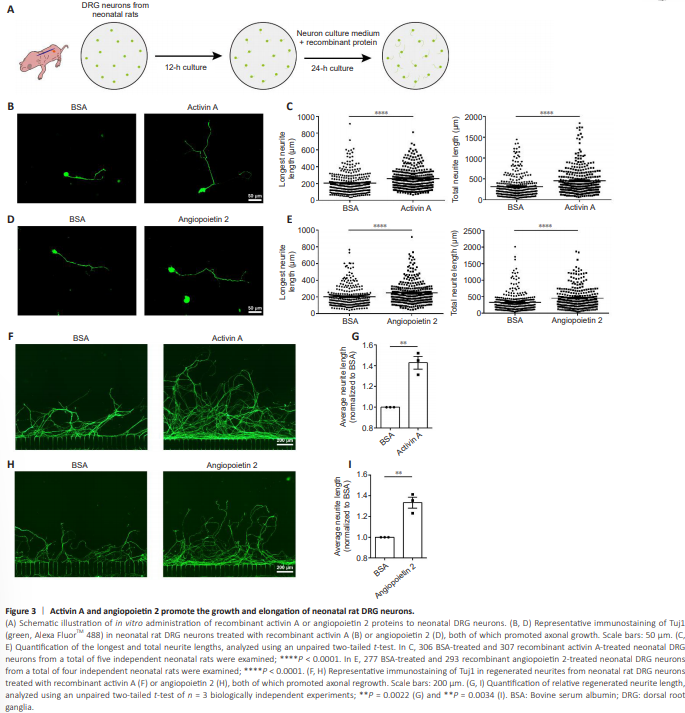

Figure 3 | Activin A and angiopoietin 2 promote the growth and elongation of neonatal rat DRG neurons.

Next, we treated cultured DRG neurons of neonatal rats with rActA or rAng2 proteins (Figure 3A). The rActA significantly increased both the longest and total neurite lengths of cultured neonatal DRG neurons. Specifically, the longest neurites increased from 204.7 ± 7.399 μm in the BSA control group to 258.7 ± 7.464 μm in the rActA group, while the total neurite length increased from 319.4 ± 15.51 μm in the BSA control group to 459.1 ± 19.05 μm in the rActA group (Figure 3B and C). Exposure to rAng2 extended the longest neurites and total neurites from 203.2 ± 7.730 μm and 333.0 ± 17.43 μm, respectively, in the BSA control group to 250.0 ± 8.217 μm and 456.4 ± 18.92 μm in the rAng2 group (Figure 3D and E).To explore the biological functions of these factors in axonal regeneration, we tested an in vitro model of axonal injury, in which axonal regeneration can be reliably quantified (Figure 3A). Neonatal DRG neurons displayed some regeneration capacity, with axons regrowing to ~800 μm at 36 hours post axonal transection. The presence of rActA or rAng2 supported injured axons in extending much farther, enhancing the average neurite length by ~40% beyond that of the BSA control group (Figure 3F–I).

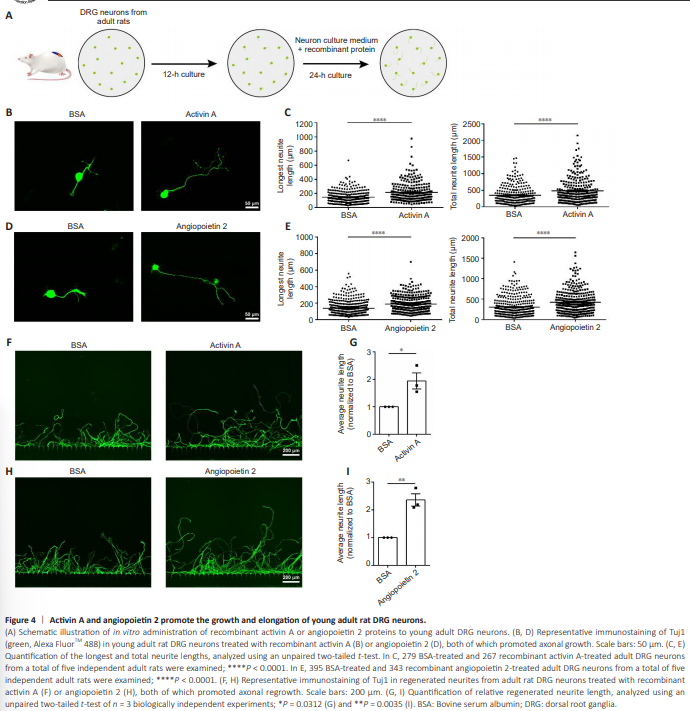

Figure 4 | Activin A and angiopoietin 2 promote the growth and elongation of young adult rat DRG neurons.

The promotional effects of rActA or rAng2 treatment on neurite growth were also observed in cultured DRG neurons of young adult rats (Figure 4A). Exposure to either rActA or rAng2 increased the longest and total neurite lengths of young adult rat DRG neurons (Figure 4B–E). In the in vitro axonal injury system, injured young adult DRG neurons from the BSA control group exhibited diminished regeneration capacity, regrowing to approximately half of the neurite length of injured neonatal DRG neurons. By contrast, the administration of rActA or rAng2 strongly enhanced axonal regrowth ability, significantly increasing the average neurite length (Figure 4F–I). These findings indicated that ActA and Ang2 are capable of potentiating the axonal growth of adult neurons and may function as neuronal growth stimulators in adult mammals.

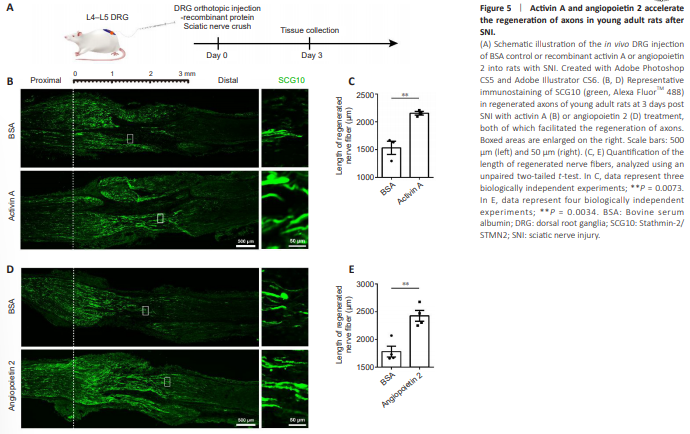

Figure 5 | Activin A and angiopoietin 2 accelerate the regeneration of axons in young adult rats after SNI.

Next, to evaluate the in vivo roles of ActA and Ang2, the recombinant proteins were directly applied to the DRGs of rats and the lengths of SCG10-positive regenerated sensory axons were compared at 3 days post sciatic nerve crush injury (Figure 5A). In young adult (8-week-old) rats, the L4–L5 injection of rActA induced a significant increase in the extension of injured nerve fibers, enhancing the length of SCG10-positive regenerated axons by 1.40 fold relative to the BSA control (Figure 5B and C). Likewise, rAng2 boosted the regeneration speed of injured axons, achieving a 36% increase in the length of the longest regenerated nerve fibers (Figure 5D and E).

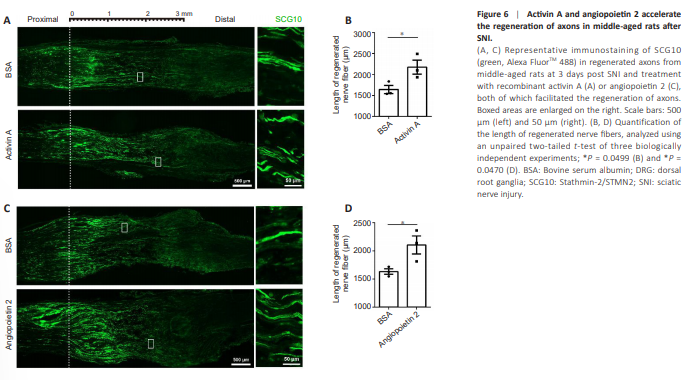

Figure 6 | Activin A and angiopoietin 2 accelerate the regeneration of axons in middle-aged rats after SNI.

Comparable promotional effects of rActA and rAng2 on the regeneration of injured nerves were observed in middle-aged (10-month-old) rats. The rActAtreated middle-aged rats showed a higher average length of regenerated nerve fibers 2175 ± 165.4 μm compared with BSA-treated middle-aged rats (1644 ± 96.06 μm; Figure 6A and B). Injection of rAng2 to the DRGs of middle-aged rats also increased the length of regenerated nerve fibers from 1631 ± 49.15 μm in the BSA control group to (2105 ± 159.6 μm; Figure 6C and D). Taken together with the findings in isolated DRG explants and cultured DRG neurons, our results have highlighted the pro-regenerative roles of ActA and Ang2 in axonal regeneration, suggesting their therapeutic potential in the treatment of peripheral nerve injury.