神经退行性病

-

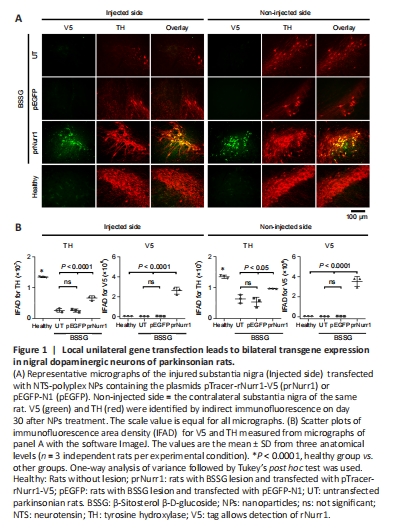

Figure 1|Local unilateral gene transfection leads to bilateral transgene expression in nigral dopaminergic neurons of parkinsonian rats.

Compared with the healthy control, the TH-IFAD in the UT group was 20% (P < 0.0001) in the ipsilateral SN and 47% (P < 0.0001) in the contralateral side. In contrast, TH-IFAD values in the prNurr1 group were 50% (P < 0.0001) in the ipsilateral SN and 72% (P < 0.0001) in the contralateral side (Figure 1). No significant difference was found between the UT and GFP transfection groups. These results suggest that rNurr1-V5 transfection increased dopaminergic neurons because IFAD values were significantly higher (P < 0.0001) than both control groups (Figure 1).

Figure 2|Local unilateral pTracer-rNurr1-V5 transfection bilaterally reduces senescence in dopaminergic neurons of parkinsonian rats.

We previously showed that senescence is a death mechanism of nigral dopaminergic neurons activated by the local unilateral BSSG administration, reaching a maximum on day 60 after the lesion in both hemispheres (Soto-Rojas et al., 2020c). Similar results were obtained in this study (Figure 2A and B). The increase in Sen-β-Gal area density was 383% (P < 0.0001) on the injured side and 426% (P < 0.0001) on the contralateral side of the UT group compared with the healthy group (Figure 2C). The pEGFP group was not different from the UT group. In contrast, the Sen-β-Gal area density values in the prNurr1 group were 131% on the injured side and 87% on the contralateral side compared with the healthy group (Figure 2C). The prNurr1 and Healthy groups show no significant difference. These results suggest that prNurr1 reduced the Sen-β-Gal staining in both substantiae nigrae, thus suggesting a reduction in dopaminergic neuron senescence (Figure 2A and B).

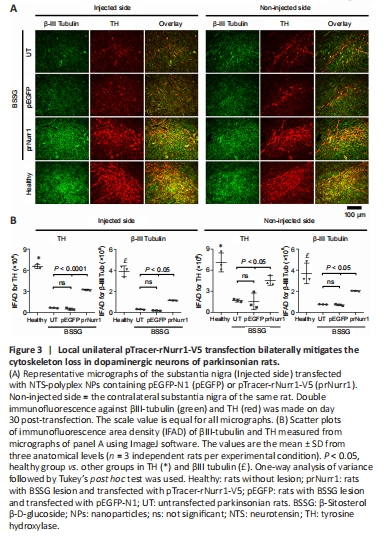

Figure 3|Local unilateral pTracer-rNurr1-V5 transfection bilaterally mitigates the cytoskeleton loss in dopaminergic neurons of parkinsonian rats.

Another evidence of dopaminergic neuron death by the unilateral administration of BSSG is the reduction of the neuronal cytoskeleton in both substantiae nigrae (Soto-Rojas et al., 2020c). Compared with the healthy group, the remaining TH+ neurons in the UT group showed TH-IFAD values of 10% (P < 0.0001) in the ipsilateral SN and 24% (P < 0.0001) in the contralateral side. In contrast, TH-IFAD values in the prNurr1 group were 49% (P < 0.0001) in the ipsilateral SN and 64% (P < 0.05) in the contralateral side (Figure 3B). The GFP group showed no significant difference from the UT group in both substantiae nigrae. The βIII-tubulin IFAD values in the UT group were 7% (P < 0.0001) in the ipsilateral SN and 20% (P < 0.0005) in the contralateral side, both compared with the Healthy group. In contrast, βIII-Tubulin IFAD values in the prNurr1 group were 30% (P < 0.0001) in the ipsilateral SN and 55% (P < 0.05) in the contralateral side (Figure 3B). βIII-tubulin IFAD values were statistically significant compared with the UT and GFP values (P < 0.05). These results suggest recovery of the cytoskeleton in dopaminergic neurons by pTracer-rNurr1-V5 gene transfection (Figure 3A and B).

Figure 4|Local unilateral pTracer-rNurr1-V5 transfection recovers dopaminergic neurons and branching in parkinsonian rats.

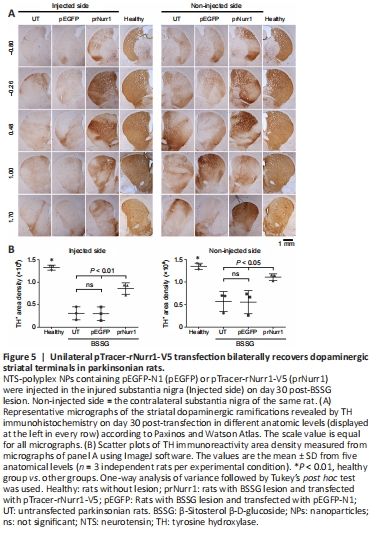

Figure 5| Unilateral pTracer-rNurr1-V5 transfection bilaterally recovers dopaminergic striatal terminals in parkinsonian rats.

In the unilateral BSSG model, senescence and reduced cytoskeleton are closely associated with neurodegeneration of both dopaminergic nigrostriatal systems with a predominance of the ipsilateral side to the lesion (Soto-Rojas et al., 2020c). Accordingly, the remaining TH+ neurons were 18% (P < 0.0001) and ramifications 20% (P < 0.0001) in the injured SNpc. They were lesser than TH+ cells (44%, P < 0.0001) and nigral ramifications (34%, P < 0.0001) in the contralateral SNpc (Figure 4A–C) compared with the health group. In addition, the decrease of nigral TH+ neurons was accompanied by low values of TH+ area density in the striatum of 23% (injured side, P < 0.0001) and 42% (contralateral side, P < 0.005) in the UT group compared with the healthy group (Figure 5A and B). Compared with the healthy group, TH+ area density in the prNurr1 group was 48% (P < 0.0001) in nigral neurons, 60% (P < 0.001) in branching, and 65% (P < 0.01) in striatal terminals on the injured side. On the contralateral side, TH+ area density was 62% (P < 0.0001) in nigral neurons, 70% (P < 0.05) in branching, and 82% (P < 0.05) in striatal terminals compared with the healthy group (Figures 4 and 5). The pEGFP group was not statistically different from UT values. In contrast, prNurr1 group values were significantly higher (P < 0.05) than those of pEGFP and UT (Figures 4 and 5). The recovery occurred throughout both nuclei and could be caused by rNurr1-V5.

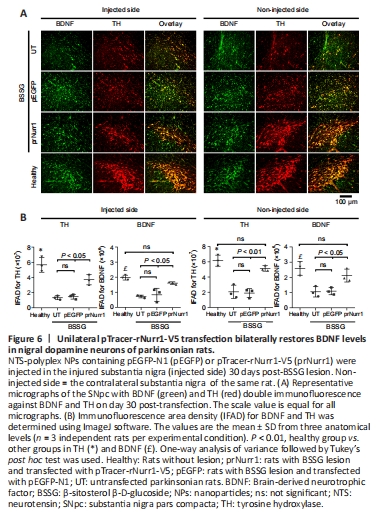

Figure 6|Unilateral pTracer-rNurr1-V5 transfection bilaterally restores BDNF levels in nigral dopamine neurons of parkinsonian rats.

The unilateral BSSG administration also bilaterally decreased BDNF-immunoreactivity in TH+ cells (Figure 6A and B), thus confirming that dopaminergic neurons are the primary source of BDNF production in the SNpc (Fernandez-Parrilla et al., 2022). BDNF-IFAD values in the UT group were 37% (P < 0.001) in the lesioned SNpc and 41% (P < 0.005) in the contralateral side compared with the healthy group (Figure 6B). BDNF-IFAD values after pTracer-rNurr1-V5 transfection were 82% in both nuclei compared with the healthy group (Figure 6B). BDNF IFAD values were statistically significant compared with UT and pEGFP groups (P < 0.05). BDNF recovery suggests that it also contributes to mitigating nigrostriatal dopamine neurodegeneration.

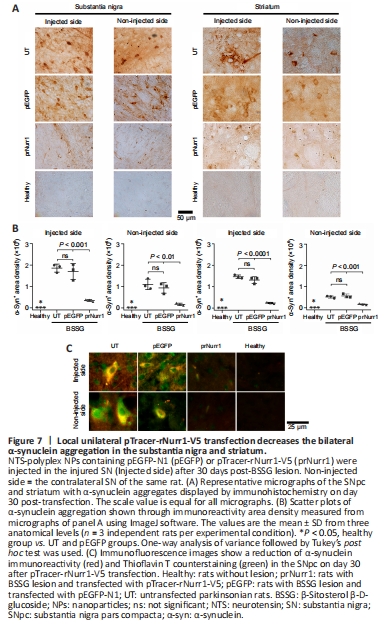

Figure 7| Local unilateral pTracer-rNurr1-V5 transfection decreases the bilateral α-synuclein aggregation in the substantia nigra and striatum.

Unilateral BSSG administration leads to increased levels of pathological α-synuclein aggregates that first appear in the injected SN and later are found in the contralateral side and both striata (Soto-Rojas et al., 2020c). Similar results were found here (Figure 7A and B). Interestingly, pTracer-rNurr1-V5 transfection but not pEGFP-N1 significantly reduced pathological α-synuclein aggregates by 81% (P < 0.001) in the injured SN and 84% (P < 0.01) in the contralateral SN of parkinsonian rats on day 30 after transfection. Furthermore, a significant decrease also occurred in both striata of the injured side (83%, P < 0.0001) and the contralateral side (69%, P < 0.001; Figure 7A and B). Moreover, pTracer-rNurr1-V5 transfection significantly decreased α-synuclein immunoreactivity and thioflavin T counterstaining in nigral neuron-like cells (Figure 7C and Additional Figure 6). These results suggest that rNurr1-V5 expression decreases pathological α-synuclein aggregation and spreading to the contralateral SN and striatum.

Figure 8| Unilateral pTracer-rNurr1-V5 transfection halts bilaterally microglial activation in the substantia nigra.

Bilateral neuroinflammation with the participation of activated microglia and neurotoxic A1 astrocytes is another indicator of unilateral BSSG-induced damage (Soto-Rojas et al., 2020c). Similar results were observed on day 60 post-BSSG administration (Figure 8 and Additional Figure 7). The Iba1 area density was 639% (P < 0.0001) in the injured SN and 373% (P < 0.005) on the contralateral side compared with the Healthy group (Figure 8 and Additional Figure 7). pTracer-rNurr1-V5 transfection yields no statistically different values to the Healthy group (ns) in both substantiae nigrae, thus reflecting attenuation of microglial activation (Figure 8).

Figure 9| Unilateral pTracer-rNurr1-V5 transfection bilaterally halts neurotoxic A1 astrocyte induction in the substantia nigra of parkinsonian rats.

Figure 10|Unilateral pTracer-rNurr1-V5 transfection bilaterally induces neurotrophic A2 astrocyte in the substantia nigra.

The reactive astrogliosis was also bilateral after BSSG administration (Additional Figure 8). Furthermore, a significant increase in IFAD for GFAP+ (1127%, P < 0.0001 in the lesioned side and 719%, P < 0.0001 in the contralateral side) and C3+ (4729%, P < 0.0001 in the lesioned side and 2389%, P < 0.001 in the contralateral side) was observed in the UT and pEGFP groups compared with the Healthy group, suggesting activation of neurotoxic A1 astrocytes (Figure 9 and Additional Figure 9). Compared with the Healthy group, IFAD values in the prNurr1 group were 506% (GFAP; P < 0.0001) and 703% (C3; P < 0.0001) in the injured SN, and 187% (GFAP; P < 0.0001) and 634% (C3; P < 0.0001) in contralateral SN. Therefore, IFAD neurotoxic A1 astrocyte values caused by pTracer-rNurr1-V5 transfection were significantly lower than those of the UT and pEGFP groups, which were no different between them (Figure 9), thus indicating that rNurr1-V5 decreased activation of neurotoxic A1 astrocytes. Only pTracer-rNurr1-V5 transfection significantly increased the double-positive S100A10-GFAP cells (neurotrophic A2 astrocytes) in the injured SN (2582% vs. healthy; 1521% vs. UT; P < 0.0001) and contralateral SN (289% vs. healthy; 450% vs. UT; P < 0.0005; Figure 10 and Additional Figure 10). These results suggest that rNurr1-V5 expression attenuated the BSSG-triggered neuroinflammatory process.