脑损伤

-

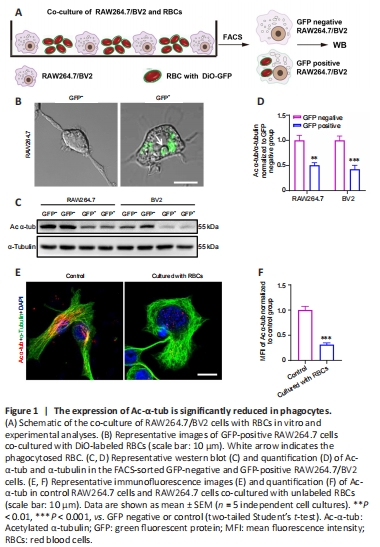

Figure 1|The expression of Ac-α-tub is significantly reduced in phagocytes.

To investigate the function of Ac-α-tub in microglia and macrophages during erythrophagocytosis, we first co-cultured the BV2 microglia cell line and RAW264.7 macrophage cell line with RBCs labeled with DiO-GFP for 12 hours (Figure 1A). GFP-positive RAW264.7/BV2 cells were collected using FACS, and imaging confirmed the engulfment of GFP-labeled RBCs by RAW264.7 cells (Figure 1B). We next examined the expression of Ac-α-tub in GFP-positive and GFP-negative cells, and the results revealed a significant reduction in the expression of Ac-α-tub in GFP-positive RAW264.7 (P < 0.01) and BV2 (P < 0.001) cells compared with GFP-negative cells (Figure 1C and D). Immunofluorescence staining also showed that the expression of Ac-α-tub was significantly reduced (P < 0.001) in RAW264.7 cells that were co-cultured with unlabeled RBCs compared with RAW264.7 cells cultured alone (Figure 1E and F). These results suggested that Ac-α-tub is downregulated in microglia/ macrophage-mediated erythrophagocytosis.

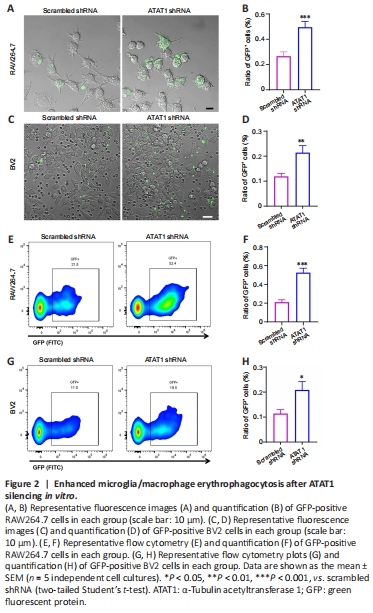

Figure 2|Enhanced microglia/macrophage erythrophagocytosis after ATAT1 silencing in vitro.

Previous studies showed that the genetic ablation of ATAT1 (also named MEC17), a specific acyltransferase for α-tubulin acetylation, induced almost complete loss of Ac-α-tub (Shida et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2022). To explore the role of Ac-α-tub in the phagocytic ability of microglia/macrophages, we first knocked down ATAT1 in RAW264.7 and BV2 cells using shRNA. After shRNA interference, the expressions of ATAT1 (P < 0.01; Additional Figure 1) and Ac-α-tub (P < 0.01; Additional Figure 2) were significantly decreased in both cell lines compared with the scrambled shRNA group. We found that the portion of GFP-positive RAW264.7 cells was significantly increased in the ATAT1 shRNA group (P < 0.001; Figure 2A and B). ATAT1 silencing also significantly increased the number of GFP-positive BV2 cells (P < 0.01; Figure 2C and D). We also quantified the number of GFP-positive phagocytes using flow cytometry and found comparable results; the number of GFP-positive RAW264.7 cells (P < 0.001; Figure 2E and F) and GFP-positive BV2 cells (P < 0.05; Figure 2G and H) were significantly increased in the ATAT1 shRNA group. These results indicated that ATAT1 knockdown enhances erythrophagocytosis by microglia and macrophages.

Figure 3|ATAT1 deficiency enhances the phagocytic ability of microglia/macrophages after ICH in mice in vivo.

To investigate the function of ATAT1 in the erythrophagocytic ability of microglia/macrophages after ICH, we used ATAT1–/– mice. We found that the expression of Ac-α-tub in microglia/macrophages from ATAT1–/– mice was significantly decreased compared with that in the WT mice (P < 0.001; Additional Figure 2). We next labeled autologous RBCs with DiO-GFP and injected the GFP-labeled RBCs into the striatum of the mice to establish the ICH model. We detected the accumulation of numerous Iba1-positive phagocytotic microglia/macrophages at the perihematomal region on day 3 after ICH (Figure 3A). Notably, although the number of Iba1-positive microglia/macrophages around the hematoma was not significantly changed in the ICHATAT1–/– group compared with the ICHWT group (P > 0.05; Figure 3A and B), the percentage of co-labeled GFP+ and Iba1+ cells within total Iba1 immune cells around hematoma was remarkably increased in the ICHATAT1–/– group (P < 0.001; Figure 3A and C). These results suggested that ATAT1 knockout enhances erythrophagocytosis of microglia and macrophage after ICH in vivo.

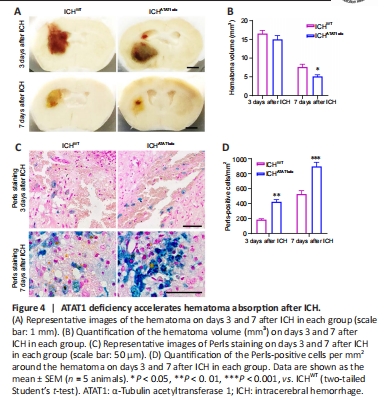

Figure 4|ATAT1 deficiency accelerates hematoma absorption after ICH.

Previous studies showed that speedy hematoma resolution results in better functional recovery following ICH (Chang et al., 2017). To investigate whether ATAT1 deficiency facilitates hematoma absorption post-ICH, we first quantified the hematoma volume in ICHWT and ICHATAT1–/– mice. While ATAT1 deficiency had no effect on the volume of the hematoma at day 3 (P > 0.05; Figure 4A and B), the hematoma volume was significantly decreased at day 7 after ICH (P < 0.05; Figure 4A and B). Hemosiderin, an intracellular and extracellular storage form of iron, appears as blue granules after Perls staining. Perls-positive cells were significantly increased around the hematoma at day 3 (P < 0.01; Figure 4C and D) and day 7 (P < 0.001; Figure 4C and D) after ICH in the ICHATAT1–/– mice compared with the ICHWT group. These results revealed that ATAT1 deficiency results in faster hematoma clearance after ICH.

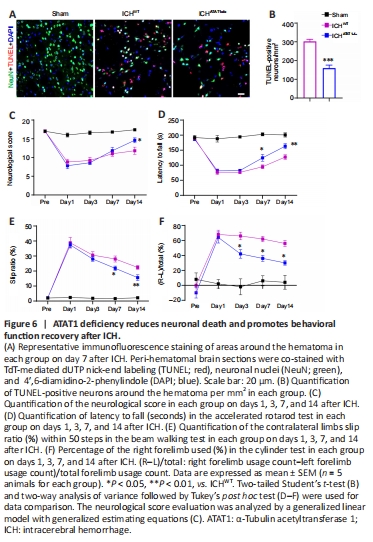

Figure 6|ATAT1 deficiency reduces neuronal death and promotes behavioral function recovery after ICH.

We next explored whether ATAT1 deficiency-induced hematoma absorption and reduced inflammation could relieve neural death and behavioral dysfunction after ICH. We examined neural apoptosis around the hematoma by co-staining with TUNEL and NeuN. The number of TUNEL-positive neurons around the hematoma was significantly decreased in the ICHATAT1–/– group on day 7 after ICH compared with the ICHWT group (P < 0.001; Figure 6A and B).

Mice were then subjected to behavioral testing using a battery of motor tests on days 1, 3, 7, and 14 after ICH. We found a significant increase in neurological score in the ICHATAT1–/– group compared with the ICHWT group on day 14 after ICH (P < 0.05; Figure 6C), suggesting holistic improvement of neurological deficits after hematoma absorption. We further performed three behavioral tests related to skilled motor function: the accelerated rotarod, beam walking, and cylinder tests. Mice in the ICHWT group showed decreased latency to fall in the rotarod text, increased slip ratio of contralateral limbs in the beam walking text, and biased use of the right forelimb in the cylinder text compared with the sham group. The ICHATAT1–/– group showed a significantly increased latency to fall in the rotarod text on days 7 (P < 0.05; Figure 6D) and 14 (P < 0.01; Figure 6D), decreased slip ratio of contralateral limbs in the beam walking text on days 7 (P < 0.05; Figure 6E) and 14 (P < 0.01; Figure 6E), and decreased use of right forelimb in the cylinder text on days 3 (P < 0.05; Figure 6F), 7 (P < 0.05; Figure 6F), and 14 (P < 0.05; Figure 6F). Taken together, these findings indicate that ATAT1 deficiency reduces neural death and promotes behavioral function after ICH.