神经退行性病

-

Figure 1 | The effects of NOX4 in an MPTP/MPP+ -induced Parkinson’s disease model.

To investigate whether NOX4 is involved in PD progression, we first explored NOX4 expression levels in the SN and striatum of mice treated with MPTP. Our results showed that NOX4 expression in the SN (P = 0.0129) and striatum (P = 0.0228) was increased in MPTP-treated mice compared with the control group (Figures 1A–D). Next, we conducted an immunofluorescence assay to determine which cell type in the SN region expresses NOX4 and to further detect changes in NOX4 expression between the MPTP and control groups. Notably, we found that NOX4 was expressed mostly in dopaminergic neurons, and at low levels in astrocytes, in the MPTP group (Figure 1E and Additional Figure 1A). Moreover, NOX4 expression levels were elevated in dopaminergic neurons (P = 0.0073) and astrocytes (P = 0.0017) in the MPTP group compared with the control group (Figure 1F and G). Consistent with the in vivo results, NOX4 expression was also increased in MN9D cells (P = 0.027) (mouse dopaminergic neuron cells) and primary astrocytes after MPP+ treatment compared with control group (P = 0.0107; Figure 1H–K). These results suggest that NOX4 may be involved in PD progression. To directly evaluate the role of NOX4 in PD development, we treated mice with GLX351322, a selective NOX4 antagonist that crosses the blood-brain barrier (Additional Figure 1B). GLX351322 treatment resulted in a significant decrease in the expression of p22phox, which is essential for NOX4 activity, in the SN compared with the MPTP group (P < 0.0001; Additional Figure 1C and D), indicating that GLX351322 has strongly inhibits NOX4 in the brain. Next, we conducted tyrosine hydroxylase immunofluorescence and western blot (WB) assays and found that NOX4 inhibition ameliorated dopaminergic neuron loss in the SN (21%, P = 0.0424), decreased TH+ fiber intensity in the striatum (18%, P < 0.0435) (Figure 1J–L), and rescued TH protein levels in the SN (20%, P = 0.0452) and striatum (30%, P = 0.0469) in the MPTP-induced PD model (Figure 1L–N and Additional Figure 1E–G). Furthermore, compared with the MPTP group, the MPTP + GLX351322 group exhibited a greater fall latency in the rotarod test (P = 0.0456; Figure 1O) and traveled farther during the open field test (P = 0.0233; Figure 1P and Additional Figure 1H). These results demonstrate that NOX4 is involved in MPTP-induced PD progression.

Figure 2 | ATF3 activates NOX4 transcription.

ATF3 promotes intracellular H2O2 production (Lu et al., 2021); therefore, we speculated that ATF3 might mediate H2O2 production by regulating NOX4 expression in dopaminergic neurons. qPCR analysis showed that ATF3 (tissues: P = 0.0332; cells: P = 0.0009) and NOX4 mRNA (tissues: P = 0.0398; cells: P = 0.0367) levels increased in mouse SN tissue and MN9D cells after MPTP or MPP+ treatment compared with the control groups (Figure 2A and B). Consistent with this, immunofluorescence and WB assays showed that ATF3 (MN9D cells P = 0.0004; PC12 cells P = 0.0009) and NOX (MN9D cells P = 0.0068; PC12 cells P = 0.0048) protein levels were markedly increased in MN9D and PC12 cells subjected to MPP+ compared with the control groups (Figure 2C–H). Moreover, siRNA-mediated silencing of ATF3 in MN9D cells reduced NOX4 expression (si-Ctrl versus si-ATF3#1, P = 0.0228; si-Ctrl versus si-ATF3#2, P = 0.0458; Figure 2I and J). These results suggest that ATF3 may upregulate NOX4 expression at the transcriptional level in MPP+ /MPTP-induced PD. To further assess the possibility that ATF3 modulates NOX4 transcription, we analyzed the NOX4 promoter using the JASPAR database (https://jaspar.genereg.net) and found that the NOX4 promoter contains two potential ATF3 binding sites (Figure 2K). Notably, ChIP analysis showed that ATF3 directly bound to these two binding sites in the NOX4 promotor after MPP+ treatment (Figure 2L). These findings suggested that MPP+ /MPTP treatment enhanced the expression of ATF3, which bound the NOX4 promoter region and promoted NOX4 transcription.

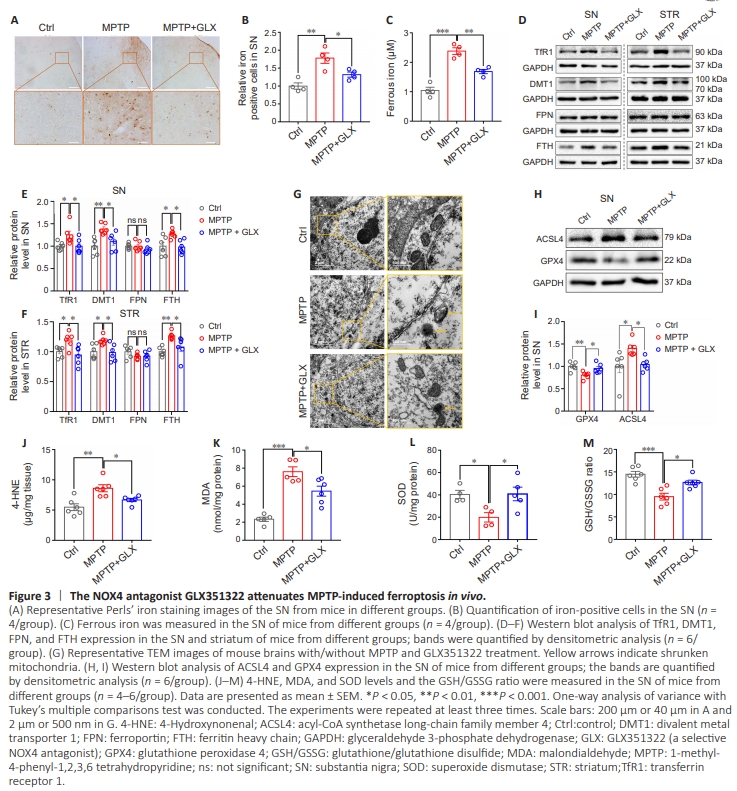

Figure 3 | The NOX4 antagonist GLX351322 attenuates MPTP-induced ferroptosis in vivo.

Although dopaminergic neuron ferroptosis in PD has been shown to primarily involve disruption of iron metabolism and lipid peroxidation, whether NOX4 can modulate iron metabolism or lipid peroxidation in the SN remained unclear. We first investigated the effect of NOX4 inhibition on the number of iron-positive cells in the SN by Perls’ iron staining. The result showed that there are more brown granules in the neuronal cytoplasm in the SN of PD model mice than control mice, and GLX351322 treatment substantially decreased the number of iron-positive cells compared with the MPTP group (P = 0.00328; Figure 3A and B). Because ferrous iron, rather than ferric iron, is implicated in ferroptosis, we next assessed the ferrous iron content of the SN and found that it was much lower in the MPTP + GLX351322 group than in the MPTP group (P = 0.0021; Figure 3C). To further explore the causes of changes in iron metabolism in the SN, we examined the expression of iron transporters in the SN and striatum, including the iron importer transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1), the divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1), the iron exporter ferroportin (FPN), and the ferrous iron storage protein ferritin heavy chain (FTH). Our results showed that TfR1, DMT1, and FTH expression in the SN (TfR1 P = 0.0441, DMT1 P =0.0031, FTH P = 0.0262) and the striatum (TfR1 P = 0.0451, DMT1 P = 0.0359, FTH P = 0.003) was increased in the MPTP group compared with the control group, while NOX4 inhibition by GLX351322 reversed this effect (SN: TfR1 P = 0.0443, DMT1 P = 0.0251, FTH P = 0.0175; striatum: TfR1 P = 0.0107, DMT1 P = 0.0239, FTH P = 0.0314). However, there was no significant difference in FPN expression among the three groups (Figure 3D–F). The changes in TfR1, DMT1, FTH, and FPN mRNA expression levels mirrored the changes seen at the protein level (Additional Figure 2A). We next performed TEM to assess neuronal ultrastructure. The results showed shrunken mitochondria and reduced mitochondrial cristae in MPTP-induced PD mice, and these effects were partially restored by NOX4 inhibition (Figure 3G). These data suggested that pharmacological inhibition of NOX4 mitigated iron accumulation in the SN by regulating iron transport.To further investigate the role of NOX4 in lipid peroxidation in a mouse model of PD, we used a dihydroethidium probe to examine ROS production in the SN and found that ROS levels in the SN were markedly increased in the MPTP group compared with the control group (P = 0.0003), while GLX351322 treatment reduced ROS levels to a level comparable to that seen in the MPTP group (P = 0.0071; Additional Figure 2B and C). Next, we examined the expression of biomarkers of ferroptosis, including glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), acyl-CoA synthetase longchain family member 4 (ACSL4), and ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1). WB analysis showed that ACSL4 expression was upregulated (SN P = 0.0268, striatum P = 0.0133) and GPX4 expression was downregulated (SN P = 0.0065, striatum P = 0.008) in the MPTP group compared with the control group, in both the SN and the striatum. These changes were reversed by treatment with GLX351322 (SN ACSL4 P = 0.0494, GPX4 P = 0.0352; striatum ACSL4 P = 0.031, GPX4 P = 0.0418; Figure 3H, I, Additional Figure 2D and E). Notably, the expression of another important ferroptosis suppressor protein, FSP1, did not differ significantly among the three groups (Additional Figure 2F and G). Additionally, levels of the lipid peroxidation byproducts MDA (P < 0.0001) and 4-HNE (P = 0.0012) were elevated in the MPTP group compared with the control group. However, MDA (P = 0.0186) and 4-HNE (P = 0.0354) expression levels decreased after GLX351322 treatment in the MPTP-induced PD group (Figures 3J and K). In contrast, the SOD level (P = 0.0488) and GSH/GSSG ratio (P = 0.0002) were downregulated in the MPTP group compared with the control group, and GLX351322 treatment restored both the SOD level (P = 0.0349) and the GSH/GSSG ratio (P = 0.0104; Figure 3L and M). Collectively, these findings demonstrated that pharmacological inhibition of NOX4 alleviated MPTP-induced dopaminergic neuronal ferroptosis by regulating iron metabolism and lipid peroxidation in vivo.

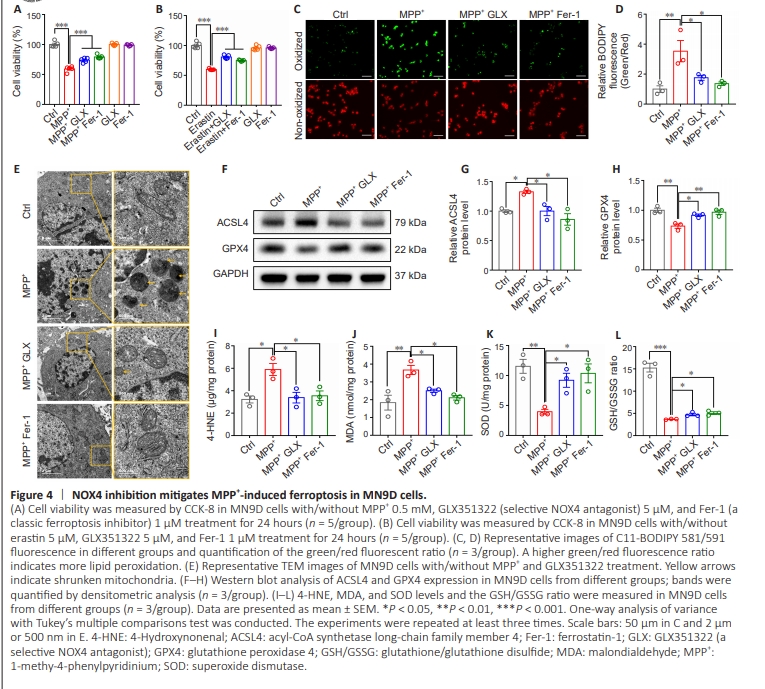

Figure 4 | NOX4 inhibition mitigates MPP+ -induced ferroptosis in MN9D cells.

Next, we explored the effect of the NOX4 antagonist GLX351322 on MPP+ -induced ferroptosis in vitro. CCK-8 analysis showed that MPP+ and erastin (a ferroptosis inducer) decreased MN9D cell viability, and this effect was reversed by treatment with GLX351322 or Fer-1 (a classic ferroptosis inhibitor) (Figure 4A and B). To assess lipid peroxidation we used a C11-BODIPY fluorescent probe that converts from red to green upon lipid peroxidation. The green/red ratio was significantly increased in the MPP+ group compared with the control group (P = 0.0072) indicating an upregulation in lipid peroxidation after MPP+ treatment. Furthermore, treatment with GLX351322 (P= 0.0466) or Fer-1 (P = 0.0172) reduced the green/red ratio in the MPP+ group, indicating that NOX4 or ferroptosis inhibition reduced MPP+ -lipid peroxidation in vitro (Figure 4C and D). TEM analysis showed that MPP+ treatment resulted in mitochondrial shrinkage and a reduction in mitochondrial cristae, while these changes were reversed by GLX351322 and Fer-1 in vitro (Figure 4E). Next, expression levels of the critical ferroptosisrelated proteins GPX4 and ACSL4 were examined by WB. MPP+ treatment led to ACSL4 upregulation (P = 0.03) and GPX4 downregulation (P = 0.0022), while treatment with GLX351322 (ACSL4: P = 0.0303, GPX4: P = 0.0199) or Fer-1 (ACSL4: P = 0.0041, GPX4: P = 0.0049) reversed these changes in vitro (Figure 4F–H). Furthermore, levels of the lipid peroxidation byproducts MDA (P = 0.0042) and 4-HNE (P = 0.0123) were elevated in the MPP+ group compared with the control group. However, NOX4 inhibition reduced the levels of both MDA (P = 0.0483) and 4-HNE in vitro (P = 0.0173; Figure 4I and J). The SOD level (P = 0.0074) and GSH/GSSG ratio (P < 0.0001) in MN9D cells were decreased in the MPP+ group compared with the control group, while NOX4 inhibition reversed these changes in vitro (SOD: P = 0.0400, GSH/GSSG ratio: P = 0.0327) (Figure 4K and L). In conclusion, these findings suggest that NOX4 inhibition alleviated MPP+ -induced dopaminergic neuronal ferroptosis by in vitro.

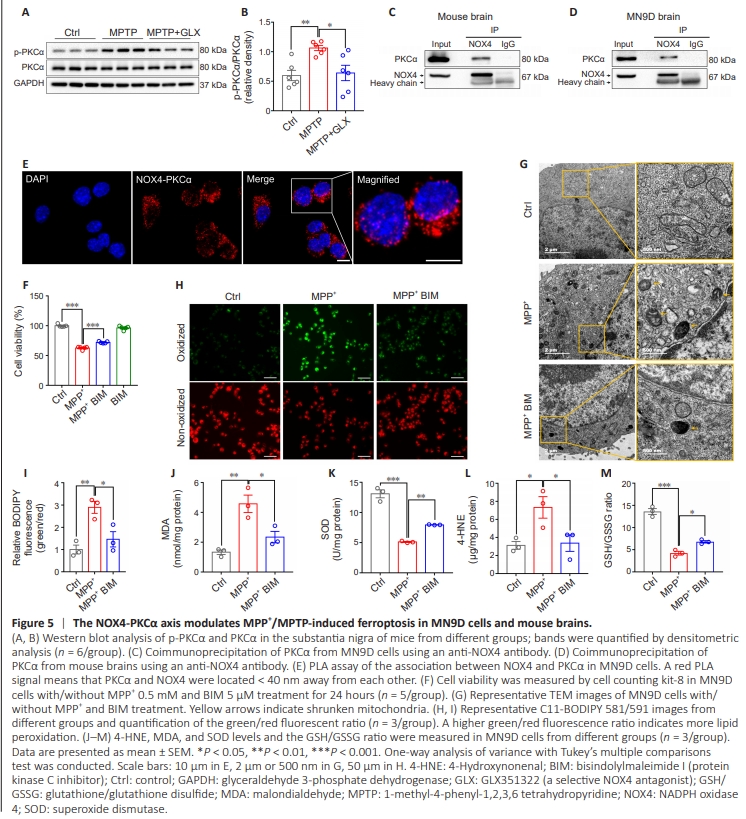

Figure 5 | The NOX4-PKCα axis modulates MPP+ /MPTP-induced ferroptosis in MN9D cells and mouse brains.

Previous studies have demonstrated that PKCα regulates ferroptosis induced by erastin in differentiated Lund human mesencephalic (LUHMES) cells, and that oxidative stress can activate PKC (Tuttle et al., 2009; Do Van et al., 2016). Therefore, we examined changes in p-PKCα and PKCα expression after treating the MPTP-induced PD model with GLX351322. WB analysis showed that p-PKCα protein expression was increased in the MPTP group compared with the control group (P = 0.0083), while NOX4 inhibition by GLX351322 reversed this change in vivo (P = 0.0159; Figure 5A and B). Immunofluorescence staining showed colocalization of NOX4 and PKCα in MN9D cells (Additional Figure 3A), and CoIP demonstrated a direct interaction between NOX4 and PKCα was observed in MN9D cells and mouse brains (Figure 5C and D). Furthermore, an in situ proximity ligation assay (PLA), which detects protein pairs located < 40 nm away from each other (Soderberg et al., 2006), showed a distinct interaction pattern between NOX4 and PKCα in MN9D cells (Figure 5E). No PLA signals were detected in MN9D cells under negative control conditions, when either of the two primary antibodies was omitted (Additional Figure 3B). To further explore the role of PKCα in MPP+ -induced ferroptosis, we first examined cell viability and found that treatment with the PKC inhibitor BIM rescued MPP+ -induced cell death (Figure 5F). Detection of ultrastructural changes by TEM showed that MPP+ treatment caused mitochondrial shrinkage and reduced mitochondrial cristae, while these changes were reversed by BIM treatment in vitro (Figure 5G). C11-BODIPY fluorescence analysis suggested that MPP+ increased intracellular lipid peroxidation in MN9D cells (P = 0.0069), and that this effect was reversed by BIM treatment (P = 0.0246) (Figure 5H and I). Moreover, PKC inhibition by BIM alleviated the MPP+ -induced increase in 4-HNE (P = 0.0484) and MDA (P = 0.0204) levels and the decrease in SOD levels(P = 0.0049) and the GSH/GSSG ratio (P = 0.0209) in MN9D cells (Figure 5J–M). Taken together, these results suggest that NOX4 interacts with and activates PKCα, thereby inhibiting MPP+ -induced ferroptosis in MN9D cells.

Figure 6 | NOX4 inhibition suppresses neuroinflammation by reducing astrocytic Lcn2 expression.

Because NOX4 localizes partially to astrocytes, we hypothesized that NOX4 could be related to neuroinflammation in our PD mouse model. Therefore, we quantified microglia and astrocytes in the SN by immunofluorescence staining with IBA1 for microglia and GFAP for astrocytes. The results showed that microglia (P = 0.0002) and astrocyte (P < 0.0001) counts increased in response to MPTP exposure, and that this effect was ameliorated by NOX4 inhibition in vivo (IBA-1: P = 0.0031, GFAP: P = 0.0016; Figure 6A–D). We next examined IL-1β and TNFα mRNA levels and found that both (IL-1β, P = 0.0215; TNFα, P = 0.0196) were significantly upregulated in the MPTP group compared with the control group, while GLX351322 treatment reversed this effect in vivo (IL-1β, P = 0.0365; TNFα, P = 0.0347; Figure 6E and F). These results revealed that NOX4 antagonist GLX351322 inhibited neuroinflammation in MPTPinduced PD models.Next, we assessed the localization and expression level of the iron-binding protein cytokine lipocalin-2 (Lcn2), which is associated with apoptotic cell death, cellular uptake of iron, and glial activation in the brain (Ferreira et al., 2015; Mann et al., 2022). Interestingly, we detected a significant increase in Lcn2 localization to GFAP-positive cells in the SN of the MPTP group compared with the control group (P < 0.0001), and this effect was reversed by GLX351322 treatment (P = 0.0239; Figure 6G and H). Moreover, WB analysis showed that Lcn2 expression was upregulated in response to MPTP treatment (P = 0.0301) but returned to control levels after NOX4 inhibition in vivo (P = 0.0468; Figure 6I and J). A previous study showed that Lcn2, which is secreted by astrocytes, is selectively toxic to neurons (Bi et al., 2013). Therefore, we asked whether dopaminergic neurons express the Lcn2 receptor (Lcn2R). Immunofluorescence analysis showed that Lcn2R localized to dopaminergic neurons (Additional Figure 4), suggesting that Lcn2 could be toxic to dopaminergic neurons in vivo. In conclusion, NOX4 activates neuroinflammation in MPTP-induced in vivo PD models through upregulating astrocytic Lcn2, which may directly induce dopaminergic neuron death.