神经退行性病

-

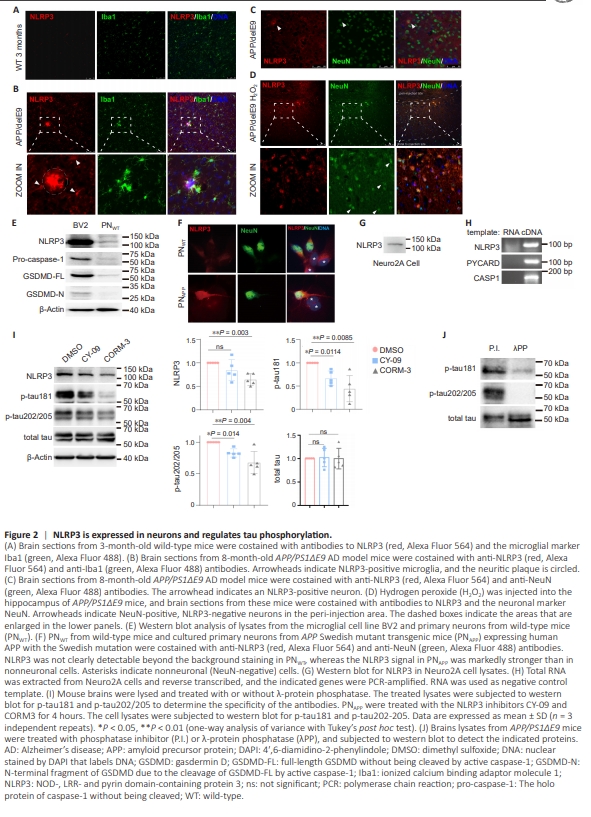

Figure 2 | NLRP3 is expressed in neurons and regulates tau phosphorylation.

To determine whether NLRP3 is expressed in neurons, we first stained the brains of 3-month-old wild-type mice and AD model mice (APP/PS1ΔE9) using an NLRP3-specific antibody. No distinct staining for NLRP3 was detected in the brains of young wildtype mice (Figure 2A). However, in APP/PS1ΔE9 transgenic mice at 8 months of age, a time point where NPs are abundant, NLRP3 staining was intense and primarily localized to the NPs surrounded by microglia. Furthermore, microglial NLRP3 expression was also upregulated (Figure 2B). In these AD brains, there was little neuronal NLRP3 expression; only occasionally were a few neurons clearly stained by the anti-NLRP3 antibody in the neocortex (Figure 2C). Upon injection of hydrogen peroxide into the hippocampus, robust NLRP3 expression was observed in the majority of neurons surrounding the injection site, with no significant upregulation of NLRP3 expression in neurons located in distal areas (Figure 2D). This suggests that neuronal NLRP3 expression is induced by oxidative stress. Western blot analysis of wild-type primary cortical neurons (PNWT) cultured in vitro showed a clear ~110 kDa band representing NLRP3. The neurons were also found to express endogenous pro-caspase-1 and GSDMD (full-length, but not the N-terminal fragment due to cleavage by activated caspase-1). However, compared with the microglia cell line BV2, these proteins were expressed at much lower levels in neurons (Figure 2E). Owing to the relatively low expression levels, cleaved forms of caspase-1 and GSDMD were undetectable in neurons, whereas cleaved GSDMD was detected in na?ve BV2 cells (Figure 2E). In PNWT cultures, NLRP3 displayed a diffuse cytoplasmic distribution, with comparable signal intensity in neurons and contaminating astrocytes (Figure 2F). However, in contrast, NLRP3 staining in primary neurons derived from APPswe mutant transgenic mice (PNAPP) was significantly enriched in neurons (Figure 2F). We further examined the mouse neuroblastoma cell line Neuro2A and found that it expressed both NLRP3 mRNA and NLRP3 protein, as well as PYCARD (encoding ASC) and CASP1 (encoding caspase-1) mRNAs (Figure 2G and H). To test whether neuronal NLRP3 helps regulate tau phosphorylation, we treated PNAPP with the NLRP3 inhibitors, CY-09 and CORM-3. Both inhibitors significantly reduced p-tau202/205 (tau with both Ser202 and Thr205 phosphorylated, recognized by the AT8 antibody) (Figure 2I). The specificity of the antibodies for phosphorylated tau was determined by treating APP/PS1ΔE9 mouse brain lysates with λ-protein phosphatase (Figure 2J). Taken together, these findings demonstrate that NLRP3 and other subunits of the N3I complex are expressed in neurons and regulate tau phosphorylation.

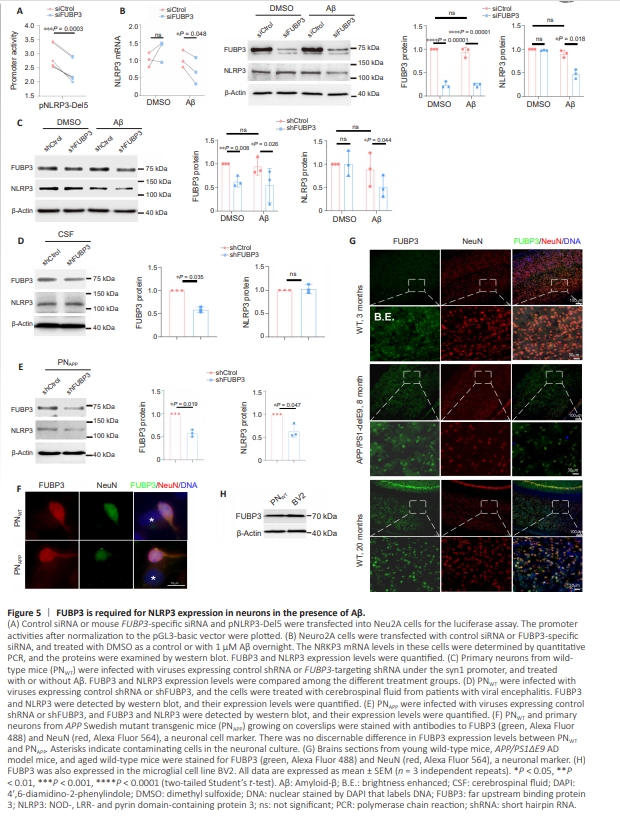

Figure 5 | FUBP3 is required for NLRP3 expression in neurons in the presence of Aβ.

To determine whether FUBP3 is required for NLRP3 promoter activity, we suppressed FUBP3 expression in Neuro2A cells using an siRNA, then transfected the cells with a plasmid containing Del5. Luciferase assay revealed that Del5 promoter activity was significantly decreased when FUBP3 expression was knocked down compared with in control siRNA–expressing Neuro2A cells (Figure 5A). Neuro2A cells express endogenous NLRP3 mRNA and protein, and therefore we first suppressed FUBP3 and examined NLRP3 expression in this cell line. Although FUBP3 protein expression was markedly decreased, there was no reduction in NLRP3 mRNA levels, and NLRP3 protein expression was unaffected by FUBP3 inhibition (Figure 5B). We further treated Neuro2A cells overnight with freshly prepared Aβ1–42 diluted in DMSO to a concentration of 1 μM to induce oligomerization. Although we did not observe any changes in NLRP3 mRNA or NLRP3 protein expression in cells expressing the control siRNA (Figure 5B), in the presence of Aβ, FUBP3 knockdown strongly reduced NLRP3 expression at both the mRNA and protein level (Figure 5B). To inhibit FUBP3 expression, primary neurons were infected with AAV9 encoding an FUBP3-targeting shRNA whose expression was driven by the neuron-specific synapsin-1 promoter (syn1). As seen in Neuro2A cells, Aβ did not appear to upregulate NLRP3 expression, and the FUBP3 shRNA inhibited NLRP3 expression only when Aβ was added to the culture (Figure 5C). In addition to Aβ, we tested whether pro-inflammatory cytokines would induce FUBP3-dependent NLRP3 expression in neurons. Because the conditioned medium derived from activated microglia enhances tau phosphorylation in neurons via pro-inflammatory cytokines, we asked whether these cytokines would stimulate neuronal NLRP3 to promote tau phosphorylation. To this end, we added mixed cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from five patients with viral encephalitis to the PNWT cultures (neurobasal medium/B27: CSF = 4:1 (v/ v), phosphate buffered saline (PBS) as control). However, FUBP3 knockdown still failed to affect NLRP3 expression in these neurons, even in the presence of CSF (Figure 5D). Hence, Aβ appears to be required for FUBP3-dependent induction of NLRP3 expression. Aβ is produced and secreted at high levels in PNAPP. FUBP3 knockdown in these neurons directly reduced NLRP3 protein levels in the absence of Aβ (Figure 5E). As primary neuron cultures may be contaminated by other cell types, mostly astrocytes, which can confound the results, we stained PNWT and PNAPP with anti-NeuN (a neuronal cell marker) and anti-FUBP3 antibodies. In both types of primary neuron cultures, FUBP3 was preferentially expressed in neurons, and only very low levels ofFUBP3 staining were observed in nonneuronal cells (Figure 5F). Therefore, the preferential expression of FUBP3 in neurons and the neuron-specific expression of the FUBP3 shRNA ensured that the effects of FUBP3 knockdown were derived from neurons, and not from contaminating cells. In young (3 months old) wild-type mice, FUBP3 was very weakly expressed in the majority of neurons in the cortex (Figure 5G). In other brain regions such as the hippocampus, only a few FUBP3- positive neurons were observed (data not shown). In the brains of 8-month-old APP/PS1ΔE9 mice, FUBP3 was markedly upregulated in almost all cortical neurons (Figure 5G). Because aging is the most important risk factor for developing AD (Sita et al., 2023; Gharpure et al., 2024), we also stained the brains of 20-monthold wild-type mice for FUBP3. Robust FUBP3 expression was detected in essentially all neurons in the cortex and hippocampus (Figure 5G). However, even in aged mice, the neuronal NLRP3 signal was undetectable above the background (Additional Figure 1). Therefore, even if increased FUBP3 expression upregulates neuronal NLRP3 expression in the absence of Aβ in vivo, the upregulation is too weak to be detected by conventional immunohistochemistry. We also did not observe FUBP3 in nonneuronal cells in the brain tissue, probably also because of the low sensitivity of immunohistochemistry. However, when examined in vitro, FUBP3 expression in BV2 cells was comparable to or stronger than that observed in PNWT cells (Figure 5H).

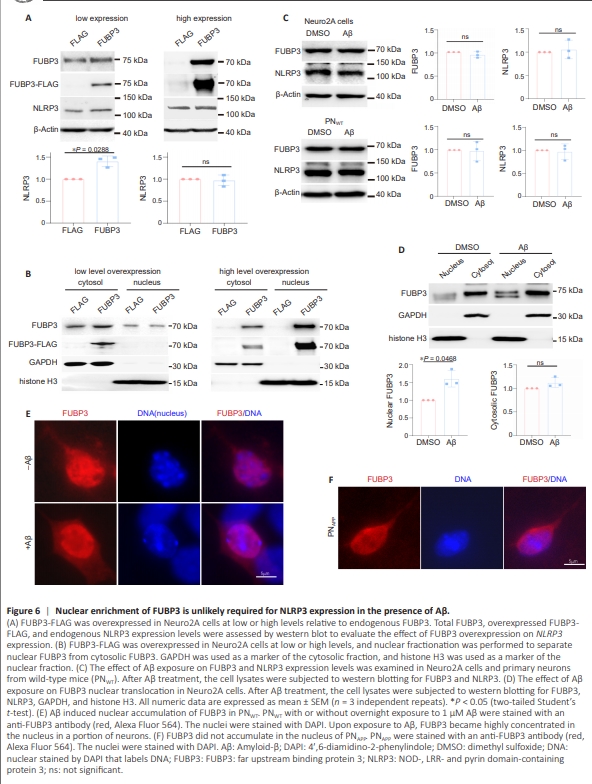

Figure 6 | Nuclear enrichment of FUBP3 is unlikely required for NLRP3 expression in the presence of Aβ.

In addition to serving as transcription factors, members of the FUBP family bind to single-stranded RNA, regulating RNA processing and translation. Thus, FUBP3 could regulateNLRP3 expression at multiple levels. Given that FUBP3 primarily localizes to the cytoplasm, if it functions as a transcription factor for NLRP3 in the presence of Aβ, it might relocate to the nucleus upon exposure to Aβ. However, Aβ does not upregulate FUBP3 expression in neurons, indicating that FUBP3 upregulation is not sufficient to increase its nuclear translocation and subsequent transcriptional activity. To assess the role of FUBP3 upregulation on NLRP3 expression in vitro, FLAG-tagged FUBP3 was overexpressed in Neuro2A cells. When overexpressed to levels comparable to endogenous FUBP3, a mild increase in NLRP3 expression was observed (Figure 6A). However, even when endogenous FUBP3 was expressed and exogenous FUBP3 was overexpressed, the majority of the FUBP3 remained cytoplasmic, and there was no increase in nuclear FUBP3 (Figure 6B). At higher overexpression levels where endogenous FUBP3 became comparatively negligible, the overexpressed FUBP3 accumulated in the nucleus (Figure 6B). This accumulation, however, appeared to be an artifact of high-level overexpression, as NLRP3 expression remained unchanged under these conditions (Figure 6A). Therefore, while an increase in FUBP3 at physiologically relevant levels contributes to NLRP3 expression, nuclear accumulation of FUBP3 does not seem to be essential for it to promote NLRP3 expression. Furthermore, treatment with Aβ did not result in FUBP3 upregulation in Neuro2A cells or PNWT (Figure 6C). To investigate whether Aβ can induce FUBP3 translocation into the nucleus without increasing its overall expression, we treated Neuro2A cells with Aβ and performed a nuclear fractionation assay. Upon Aβ treatment, we observed a mild but significantincrease in the ratio of nuclear FUBP3 to cytoplasmic FUBP3 (Figure 6D). However, in PNWT, FUBP3 appeared to be diffusely distributed throughout most neurons, lacking a specific localization pattern (Figure 6E). Notably, a subset of neurons with larger soma showed clear enrichment of FUBP3 in the nucleus (Figure 6E). Treatment with Aβ resulted in an increase in the percentage of neurons exhibiting nuclear FUBP3 enrichment, ranging from ~20% to 70%. This response to Aβ was variable even among neurons from littermate embryos. Interestingly, in PNAPP, where Aβ production is elevated and FUBP3 directly regulates NLRP3 expression, no nuclear accumulation of FUBP3 was observed (Figure 6F). These findings suggest that Aβ likely induces FUBP3-dependent NLRP3 expression by activating FUBP3, and that nuclear accumulation of FUBP3 beyond basal levels is not required for NLRP3 expression in the presence of Aβ.