神经退行性病

-

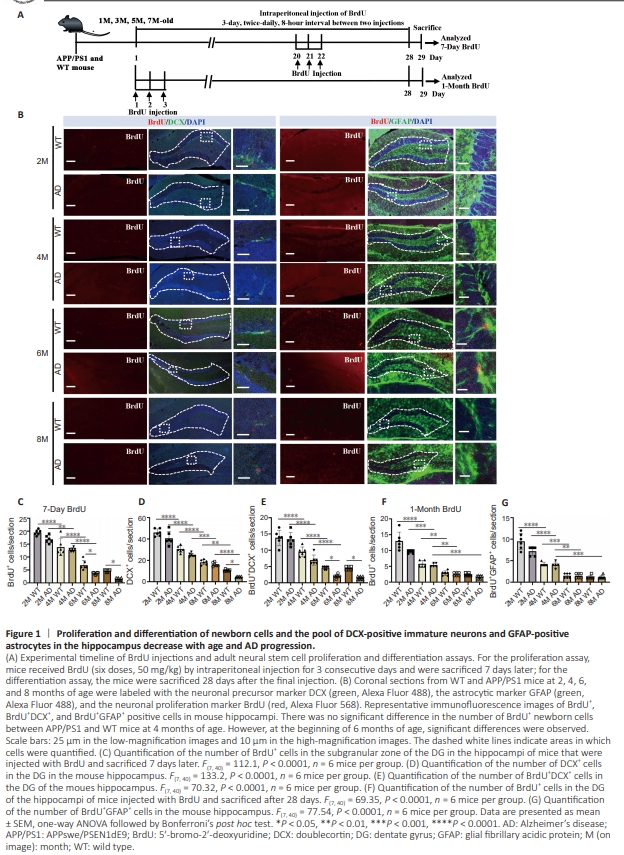

Figure 1 | Proliferation and differentiation of newborn cells and the pool of DCX-positive immature neurons and GFAP-positive astrocytes in the hippocampus decrease with age and AD progression.

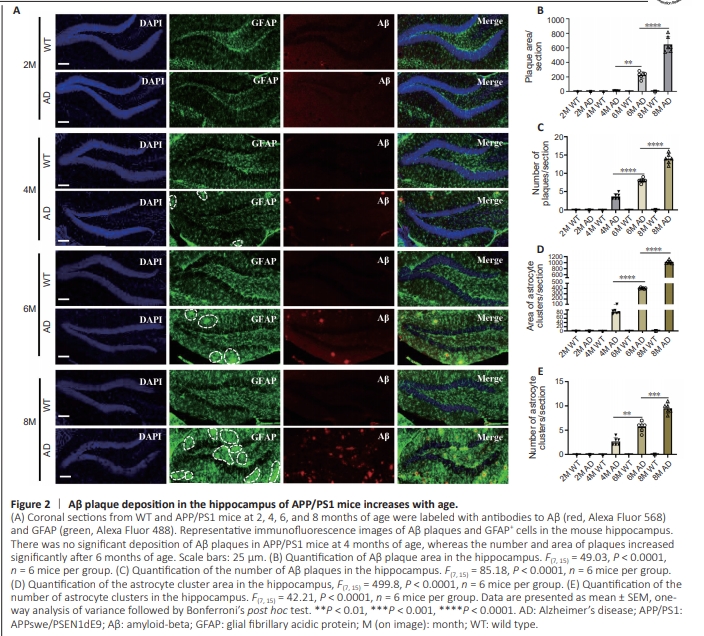

Figure 2 | Aβ plaque deposition in the hippocampus of APP/PS1 mice increases with age.

To understand the dynamics of adult neurogenesis and Aβ plaque burden in the hippocampus, we analyzed brain slices from WT and APP/PS1 mice at 2, 4, 6, and 8 months of age. We detected cell proliferation in the mouse brain by administering BrdU, and performing immunofluorescence staining of the brain tissue (Figure 1A). First, we detected changes in the numbers of newborn hippocampal cells (BrdU+ cells) and immature neurons (DCX+ cells) in 2-, 4-, 6- and 8-month-old mice by quantitative immunohistochemical analysis (Figure 1B). We observed a general age-related decrease in BrdU+ cells and DCX+ cells among WT and APP/PS1 mice (Figure 1C and D). Notably, there were no significant differences in BrdU+ and DCX+ cell counts between WT and age-matched APP/PS1 mice prior to 4 months of age. However, at 6 months of age, a significant decrease in the number of BrdU+ cells was observed in APP/PS1 mice compared with age-matched WT mice. This trend continued and became more pronounced as AD progressed, indicating an AD-dependent reduction in cell proliferation (Figure 1C and D). To investigate newborn neuron differentiation, we quantified newborn immature neurons (BrdU+ /DCX+ cells) in the hippocampal region and found that the number of newborn immature neurons gradually decreased as the mice aged and AD progressed,suggesting that neuronal development is affected by both age and disease (Figure 1E). To further investigate the correlation between astrocyte development and AD progression, we collected brain tissue from mice at 2, 4, 6, and 8 months of age and performed fluorescence double-labeling for BrdU+ /GFAP+ cells (astrocytes) in the hippocampal region (Figure 1B). The quantitative results demonstrated a descending trend in the number of BrdU+ cells and new astrocytes (BrdU+ / GFAP+ cells) in both WT and APP/ PS1 mice during the aging process. Notably, this decline was more precipitous in both WT and APP/PS1 mice after 6 months of age, indicating that astrocyte development is influenced by age (Figure 1F and G). To investigate dynamic amyloid accumulation and morphological changes in astrocytes (GFAP+ cells) in the hippocampus, we subjected brain sections from WT and APP/PS1 mice aged 2, 4, 6, and 8 months to immunofluorescence staining (Figure 2A). The results clearly demonstrated an increase in the number of Aβ plaques and the fraction of plaque area in the hippocampus of APP/PS1 mice between 4 and 8 months of age, while no significant changes were observed in WT mice (Figure 2B and C). Morphologically, no Aβ plaques were observed in the hippocampus of the APP/PS1 mice at 2 months of age, consistent with a previous report indicating that amyloid plaques begin to form in APP/PS1 mice at 3 months of age (Zhu et al., 2017). Small and sporadic plaques were observed in 4-month-old APP/ PS1 mice, progressing to larger and more compact plaques by 6 months of age. By 8 months of age, there was a significant accumulation of larger and more diffuse plaques, indicating a progressive increase in Aβ burden in APP/PS1 mice with age. Additionally, brain sections stained with anti-GFAP antibodies revealed alterations in astrocyte profiles in APP/PS1 mice at different time points (Figure 2A). Although occasional clusters of GFAP-positive astrocytes were observed in the hippocampus of 4-month-old APP/PS1 mice, there was a consistent increase in both the number and size of these clusters with advancing age in APP/PS1 mice (Figure 2D and E). Double-labeling for both GFAP and Aβ confirmed that the clusters of GFAP+ astrocytes were located adjacent to amyloid plaques. Furthermore, the increase in the total area of the hippocampus occupied by GFAP-positive astrocytes correlated with the increase in the Aβ-positive area in APP/PS1 mice, indicating that glial cells proliferated in response to Aβ accumulation. Taken together, these findings indicate that the number of BrdU+ cells, DCX+ cells, BrdU+ /DCX+ cells, and BrdU+ / GFAP+ cells in the hippocampus decreased with age, accompanied by a robust increase in Aβ plaque deposition with AD progression, suggesting an age-related reduction in adult neurogenesis combined with an elevation in Aβ burden in APP/PS1 mice. Conversely, no significant changes in hippocampal neuroblast proliferation and differentiation were observed between WT and APP/PS1 mice at 2 and 4 months of age, despite the presence of Aβ plaques in APP/PS1 mice at the age of 4 months, indicating that the deterioration in neurodevelopment may not be directly caused by Aβ plaque accumulation in the early stages of AD.

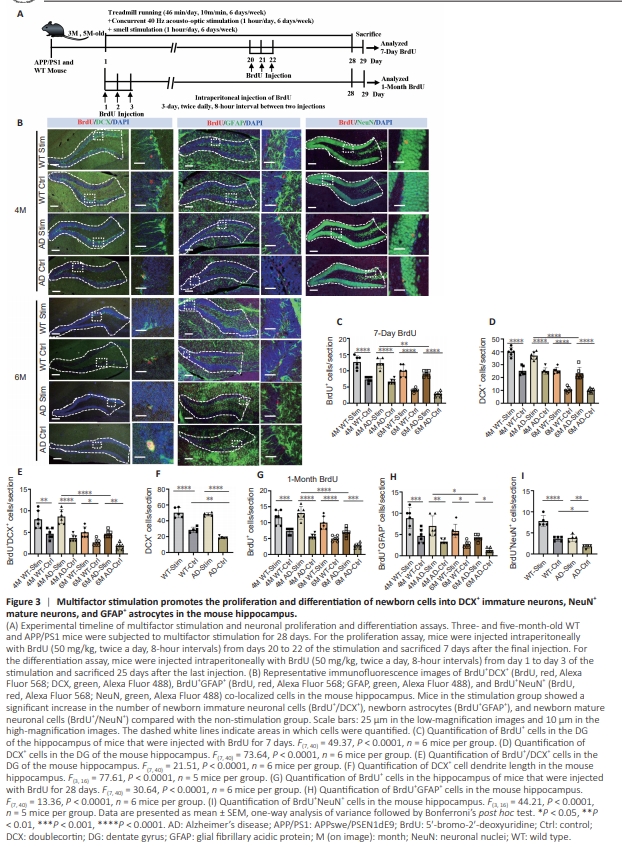

Figure 3 | Multifactor stimulation promotes the proliferation and differentiation of newborn cells into DCX+ immature neurons, NeuN+ mature neurons, and GFAP+ astrocytes in the mouse hippocampus.

To assess whether multifactor stimulation can enhance neuroblast proliferation and promote the differentiation of newborn cells into neurons and astrocytes, thereby preventing neurodevelopmental degeneration, we treated 3- and 5-monthold WT and APP/PS1 mice with or without multifactor stimulation for 4 weeks and injected them with BrdU (Figure 3A). At the end of the stimulation period, the mice were sacrificed, their brains were harvested, and the dentate gyrus region of the hippocampus was stained with anti-BrdU and anti-DCX antibodies (Figure 3B). The mice subjected to multifactor stimulation exhibited a notable increase in BrdU+ neonatal cells (Figure 3C), DCX+ immature neurons (Figure 3D), and DCX+ /BrdU+ newborn immature neurons (Figure 3E) in the hippocampal region in comparison to their agematched non-stimulation counterparts, indicating that multifactor stimulation was beneficial for early neuronal proliferation and differentiation among neural stem cells. Notably, a significantly higher number of DCX+ immature neurons, BrdU+ newborn cells, and DCX+ BrdU+ newborn immature neurons were observed in the hippocampi of stimulated APP/PS1 mice at 4 months than at 6 months of age, implying that the stimulation was more effective in the early stages of AD (Figure 3C–E). Because multifactor stimulation substantially increases the total number of DCX+ cells in the hippocampus, we next asked whether it could also alter the dendritic length of DCX+ cells. We found that 4-monthold untreated APP/PS1 mice exhibited shorter DCX+ cell dendrite lengths than age-matched untreated WT mice, while multifactor stimulation restored dendrite length in APP/PS1 mice (Figure 3F). These results imply that multifactor stimulation improved the morphology of immature neurons. Moreover, a greater number of hippocampal BrdU+ cells and BrdU+ /GFAP+ astrocytes were observed in the stimulation groups compared with the non stimulation groups for both WT mice and APP/PS1 mice (Figure 3G and H), indicating that multifactor stimulation increased the number of newborn GFAP+ astrocytes in the hippocampus of young mice. Conversely, the number of hippocampal BrdU+ cells and BrdU+ /GFAP+ astrocytes was significantly enhanced in stimulated APP/PS1 mice at 4 months than at 6 months of age, indicating that multifactor stimulation was more conducive to the development of astrocytes in the early phase of AD (Figure 3G and H). To assess the effect of multifactor stimulation on newborn cell neuronal differentiation, we next performed BrdU+ NeuN+ immunofluorescence staining. BrdU+ /NeuN+ cell proliferation in the hippocampus was markedly elevated in the stimulation group compared with the age-matched control group, indicating that multifactor stimulation increased the production of newborn neurons (Figure 3I).

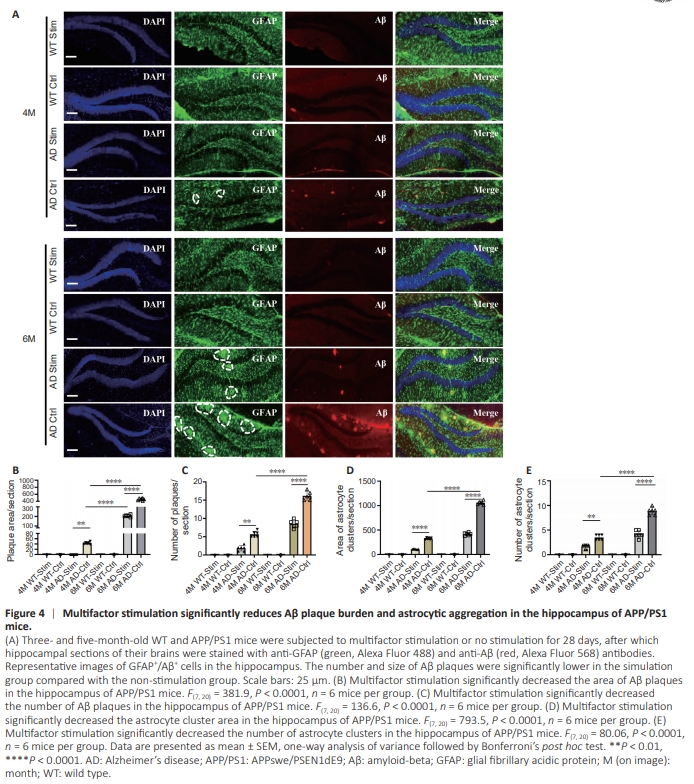

Figure 4 | Multifactor stimulation significantly reduces Aβ plaque burden and astrocytic aggregation in the hippocampus of APP/PS1 mice.

To determine whether multifactor stimulation could alter Aβ burden and astrocyte morphology, GFAP/Aβ doubleimmunostaining was performed in 4- and 6-month-old WT and APP/PS1 mice 4 weeks after the stimulation protocol was completed (Figure 4A). Quantification showed that the size and number of Aβ plaques located in the hippocampus of APP/ PS1 mice were significantly reduced in the stimulation group compared with the control group, suggesting that multifactor stimulation ameliorated the Aβ burden (Figure 4B and C). More interestingly, considerably less amyloid deposition was observed in the hippocampus of 4-month-old APP/PS1 mice in the stimulation group compared with the non-stimulation group, indicating that multifactor stimulation in the early stage of AD restored Aβ deposition to normal levels (Figure 4B and C). Moreover, the number and size of GFAP+ astrocyte clusters were significantly reduced in treated transgenic mice between 4 and 6 months of age compared with their untreated age-matched transgenic counterparts, implying that multifactor stimulation alleviated astrocyte aggregation (Figure 4D and E). Collectively, these findings suggest an active and effective treatment of that multifactor stimulation actively and effectively promotes adult neurogenesis and reduces Aβ deposition in the early stages of AD neuropathology.

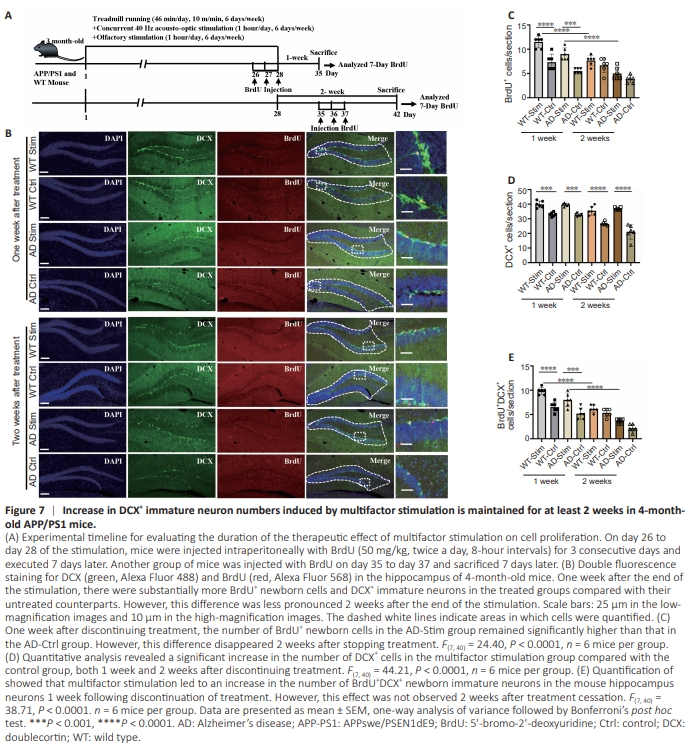

Figure 7 | Increase in DCX+ immature neuron numbers induced by multifactor stimulation is maintained for at least 2 weeks in 4-monthold APP/PS1 mice.

We demonstrated that multifactor stimulation promoted hippocampal adult neurogenesis; however, the optimal duration of treatment remained unclear. To investigate this, we examined the impact of multifactor stimulation on adult neurogenesis 1 and 2 weeks following termination of treatment using immunofluorescence staining. Three-month-old WT and APP/PS1 mice underwent 28-day multifactor stimulation treatment and BrdU administration (Figure 7A). BrdU and DCX double immunofluorescence staining revealed the presence of BrdU+ newborn cells and DCX+ immature neurons in the mouse hippocampi (Figure 7B). Quantitative analysis demonstrated a significant increase in the number of BrdU+ newborn cells (Figure 7C), DCX+ immature neurons (Figure 7D), and BrdU+ / DCX+ newborn immature neurons (Figure 7E) in the treated groups compared with their untreated counterparts 1 week after termination of treatment. However, the number of BrdU+ newborn cells and BrdU+ /DCX+ newborn immature neurons was less pronounced 2 weeks after the last stimulation (Figure 7C and E). These findings suggest that the stimulation-induced newborn neuron production lasted for only 1 week. Nevertheless, even up to 2 weeks after stopping treatment, the number of DCX+ immature neurons in the hippocampus remained higher in the treated mice compared with the untreated mice, suggesting that multifactor stimulation effectively enhances the pool of immature neurons (Figure 7D).

Figure 8 | Increase in newborn GFAPpositive cells induced by multifactor stimulation is maintained for 1 week in 4-month-old APP/PS1 mice.

To verify the duration of multifactor stimulation on mature neuronal differentiation, BrdU/GFAP double-immunostaining was carried out 1 and 2 weeks after the final treatment. Threemonth-old WT and APP/PS1 mice underwent a 28-day multifactor stimulation treatment and were injected with BrdU (Figure 8A). Consistent with the findings described earlier, the numbers of BrdU+ newborn cells and BrdU+ /GFAP+ newborn mature astrocytes were significantly elevated in the stimulated groups compared with the non-stimulated groups 1 week after cessation of treatment (Figure 8B–D). However, this difference was no longer statistically significant 2 weeks after therapy was discontinued (Figure 8C and D). Collectively, these results suggest that the enhanced production of newborn neurons and astrocytes persists for approximately 1 week following cessation of treatment, while a whole generation of the immature neuron pool persists for at least 2 weeks after treatment discontinuation.