神经退行性病

-

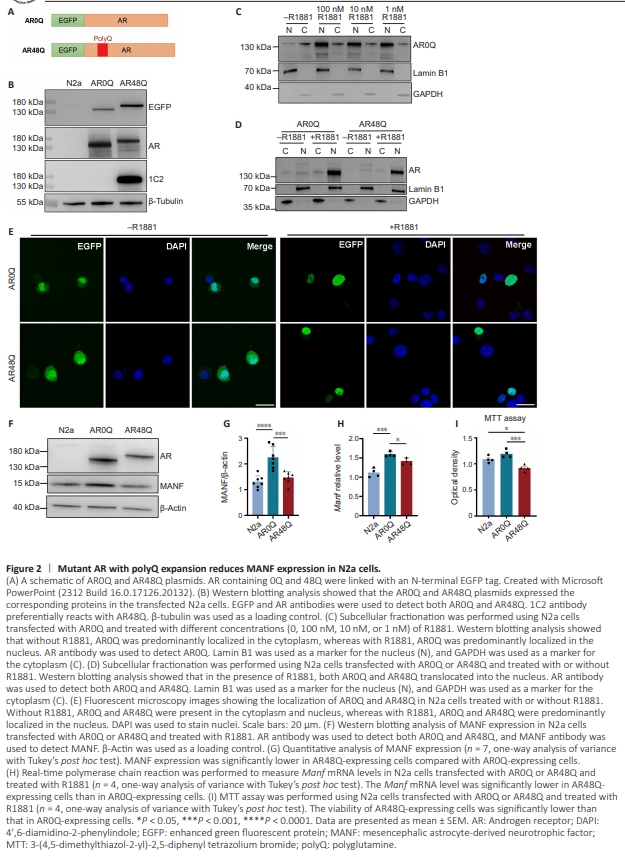

Figure 2 | Mutant AR with polyQ expansion reduces MANF expression in N2a cells.

Next, we studied the potential influence of AR with different polyQ lengths on MANF expression in N2a cells. We used the pEGFP-C1 AR plasmids that were generated in a previous study (Stenoien et al., 1999), in which AR0Q and AR48Q were linked with an enhanced GFP (EGFP) tag and driven by the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter (Figure 2A). The AR0Q functions as normal AR and AR48Q functions as mutant AR (Stenoien et al., 1999). We transfected these two plasmids into N2a cells, and the cells were kept for 48 hours before collection for analyses. Western blotting with the AR and EGFP antibodies verified the expression of AR0Q and AR48Q, respectively. In addition, the 1C2 antibody preferentially reacts with the expanded polyQ repeats, and thus it only recognizes AR48Q (Figure 2B). AR is localized in the cytoplasm in the absence of its ligand, but translocates into the nucleus to control transcription when its ligand is added (Simental et al., 1991; Georget et al., 1997). To confirm that this phenomenon occurs in N2a cells, we performed subcellular fractionation to separate the cytoplasmic and nuclear components of N2a cells. Western blotting analysis showed that the transfected AR0Q was predominantly located in the cytoplasm. We also added various concentrations (1, 10 and 100 nM) of synthetic androgen R1881 to the culture medium of the N2a cells for 24 hours, and found that all of the concentrations of R1881 induced AR0Q translocation to the nucleus (Figure 2C). To minimize the potential toxicity of R1881 at high concentrations, we used the lowest concentration (1 nM) for the subsequent experiments because this concentration was able to promote the nuclear translocation of both AR0Q and AR48Q in the N2a cells (Figure 2D). This result was further confirmed by fluorescent microscopy imaging because the EGFP signals for AR0Q and AR48Q were predominantly seen in the nucleus of the transfected N2a cells after 1nM R1881 treatment (Figure 2E). We then examined MANF expression in the N2a cells treated with R1881. Compared with the non-transfected N2a cells, the N2a cells transfected with AR0Q showed a significantly higher level of MANF, suggesting that AR0Q promotes MANF expression. In contrast, MANF expression was significantly lower in the N2a cells expressing AR48Q compared with cells expressing AR0Q (Figure 2F and G). We also measured the level of Manf mRNA in the transfected N2a cells using quantitative real-time PCR. The AR0Q-expressing cells had significantly higher Manf mRNA levels compared with the AR48Q-expressing cells (Figure 2H), a result that was consistent with the protein expression results. Given that MANF is a protective molecule, we performed an MTT assay to examine the viability of the N2a cells transfected with AR0Q or AR48Q. The optical density of AR48Q-expressing cells was significantly lower than that of untransfected or AR0Q-expressing cells (Figure 2I), suggesting that the expression of AR48Q, but not AR0Q, caused cell death. Together, these results indicate that normal AR promotes MANF expression in cultured cells, but that mutant AR with polyQ expansion is not as effective in such a function.

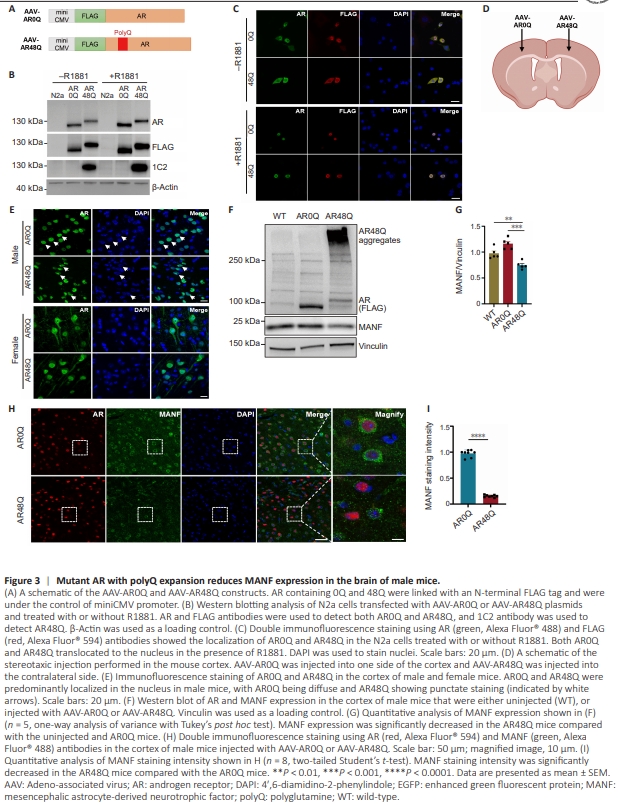

Figure 3 | Mutant AR with polyQ expansion reduces MANF expression in the brain of male mice.

We next wanted to expand our observation to in vivo conditions, in the mouse brain. We constructed AAVAR0Q and AAV-AR48Q with a FLAG tag under the control of the miniCMV promoter (Figure 3A). The plasmids were transfected into the N2a cells, and the expression of AR0Q and AR48Q was confirmed by western blotting using AR, FLAG and 1C2 antibodies (Figure 3B). Immunofluorescence staining also confirmed that both AR0Q and AR48Q translocated to the nucleus upon R1881 treatment (Figure 3C), indicating that these AAV plasmids functioned similar to the original pEGFP-C1 plasmids. These AAV plasmids were packaged into viruses. We then performed stereotaxic surgery to deliver AAV-AR0Q to one side of the cortex and AAV-AR48Q to the contralateral cortex in 2-month-old WT mice (Figure 3D). The mice were sacrificed 1 month after viral injection. We performed immunofluorescence staining to examine the subcellular localization of AR in the brains of the injected mice. In female mice, because of their low androgen levels, both AR0Q and AR48Q were diffuse in the nucleus and cytoplasm of neurons. In the neurons of male mice, because of the presence of abundant androgen, both AR0Q and AR48Q were predominantly located in the nucleus. More importantly, in the male mice, AR48Q, but not AR0Q, formed aggregates in the nucleus, as evidenced by the uneven fluorescent staining patterns (Figure 3E). Therefore, to model the pathogenic environment of SBMA, we used male mice for the subsequent analyses. Western blotting confirmedthe expression of AAV-AR0Q and AAV-AR48Q in the brains of the injected mice. Notably, the aggregated forms of AR48Q were found in the stacking gel, which was consistent with the immunofluorescence staining results. We found that MANF expression was significantly decreased in the AAV-AR48Q mice compared with that in the uninjected mice or the AAVAR0Q mice (Figure 3F and G), suggesting that mutant AR impaired MANF expression in the mouse brain. This result was corroborated by immunofluorescence staining because the staining intensity of MANF was significantly decreased in the AR48Q mice compared with the AR0Q mice (Figure 3H and I)

Figure 4 | Mutant AR with polyQ expansion causes neuronal damage in the cortex of WT mice.

To examine if AR48Q induces neuronal damage, we measured the expression of several marker proteins, including neuronal marker NeuN, postsynaptic marker PSD95, dendritic marker MAP2, and reactive astrocyte marker GFAP (Feng and Zhang, 2009; Yang et al., 2017b; Bodakuntla et al., 2019). Compared with the AR0Q mice, the AR48Q mice had significantly decreased expression of NeuN, PSD95 and MAP2, and significantly increased expression of GFAP (Figure 4A and B), suggesting that AR48Q caused neuronal damage in the cortex of WT mice. We also performed immunofluorescence staining using cortical slices of the injected mice. In the AR48Q mice, the staining intensities of NeuN and MAP2 were significantly diminished compared with those in the AR0Q mice (Figure 4C– F), which was consistent with the western blotting results. To further investigate whether the changes in protein expression were associated with actual neuronal loss, we performed Nissl staining to label neurons. In the AR48Q mice, neuronal density was significantly decreased compared with that in the AR0Q mice (Figure 4G and H). In addition, the staining intensity of GFAP was significantly increased by AR48Q (Figure 4I and J), indicating elevated astrocyte reactivity. We also performed TUNEL staining, which is a classical method that detects DNA breaks formed in the last phase of apoptosis (Mirzayans and Murray, 2020). The AR48Q mice had an obvious increase of TUNEL-positive signals compared with the AR0Q mice (Figure 4K and L). Together, these results indicate that mutant AR with polyQ expansion causes neuronal dysfunction and death in the cortex.

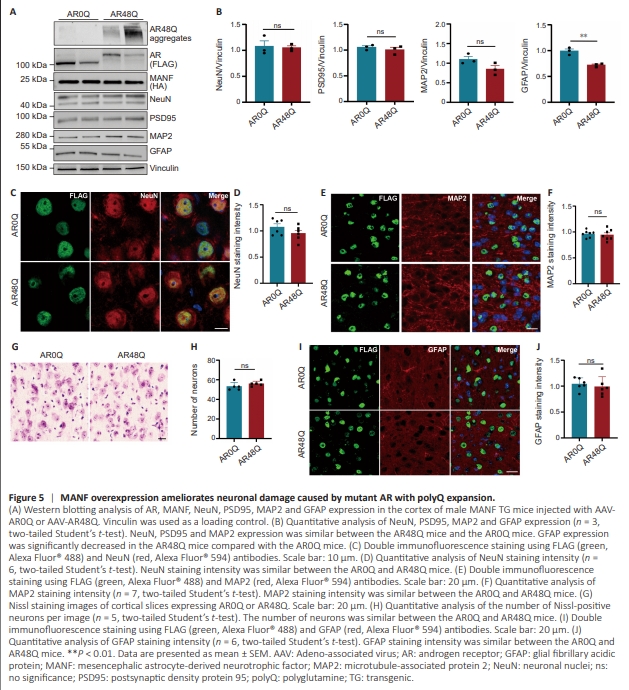

Figure 5 | MANF overexpression ameliorates neuronal damage caused by mutant AR with polyQ expansion.

If reduction of MANF expression underlies the neurotoxicity induced by mutant AR, we expected that increasing MANF expression would ameliorate the neuropathology. To investigate this, we used a MANF TG mouse model established in our previous study, in which TG Manf was driven by the prion promoter so that MANF was overexpressed in the brain (Yang et al., 2014). We performed stereotaxic surgery to deliver AAV-AR0Q to one side of the cortex and AAV-AR48Q to the contralateral side in 2-month-old MANF TG mice. These mice were sacrificed 1 month after viral injection. Western blotting analysis showed that the expression of NeuN, PSD95, and MAP2 was similar between the AR0Q and AR48Q mice, whereas GFAP expression was decreased in the AR48Q mice compared with that in the AR0Q mice (Figure 5A and B), indicating that MANF overexpression ameliorated the neurotoxicity of AR48Q. Immunofluorescence staining showed that the NeuN and MAP2 intensities were similar in the AR0Q and AR48Q mice (Figure 5C–F). This result was supported by Nissl staining, which showed no obvious neuronal loss in the cortex of the AR48Q mice (Figure 5G and H). We also performed GFAP staining and found similar levels of reactive astrocytes in the cortex of MANF TG mice expressing AR0Q or AR48Q (Figure 5I and J).