神经退行性病

-

Figure 1 | Chitosan alleviates motor dysfunction and improves DA neuron survival in an MPTP-induced mouse model of PD.

Female mice have a higher death rate and experience more side effects than male mice following MPTP exposure (Jackson-Lewis and Przedborski, 2007), so only male mice were used in this study. Male C57BL/6J mice (18–22 g, 8 weeks old) were obtained from the Animal Center, Kunming Medical University, China (license No. SCXK (Dian) K2020-0004). The Animal Ethics Committee of Kunming Medical University approved the study (approval No. kmmu20220443; approval date: February 21, 2022). All experiments were designed and reported according to Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines (Percie du Sert et al., 2020). All mice were housed in a controlled, specific pathogen-free environment (temperature, 23 ± 3°C; humidity, 55% ± 15%, 12/12-hour light/dark cycle) with free access to food and water. Body weights were recorded daily. As shown in Figure 1A, the mice were randomly divided into seven groups: (1) the control group (n = 26), which received 125 μL normal saline via intraperitoneal injection once daily for 5 days; (2) the MPTP group (PD model group) (n = 26), which treated with MPTP-HCl (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA, M0896, 30 mg/kg) via intraperitoneal injection once daily for 5 days, followed by intragastric administration of 200 μL of 0.5% acetic acid (Tianjin Zhiyuan Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., China) once daily for 26 days; (3) the MPTP + chitosan group (chitosan group) (n = 32), which was treated with same dosage of MPTP-HCl via intraperitoneal injection for 5 days, followed by intragastric administration of 200 μL of 0.5% chitosan (5 mg/mL, TCI, Tokyo, Japan, C0831) in 0.5% acetic acid once daily for 26 days; (4) the MPTP + chitosan + acetate [NaA]/butyrate [NaB]/propionate [NaP]/ short-chain fatty acid [SCFAs] mixture group (NaA/NaB/NaP/SCFAs group) (n = 10 per group), which received the same treatment as the chitosan group, followed by oral administration of 67.5 mM sodium acetate (Sigma, S2889), 25 mM sodium propionate (Sigma, P1880), 40 mM sodium butyrate (Sigma, 303410), or a mixture of SCFAs (67.5 mM acetate, 40 mM butyrate, 25 mM propionate) for 28 days); (5) the control + NaA group (n = 4), which received the same treatment as the control group, followed by oral administration of 67.5 mM sodium acetate for 28 days; (6) the MPTP + NaA group (n = 4), which received the same treatment as MPTP group, followed by oral administration of 67.5 mM sodium acetate for 28 days; and (7) the peroxisome proliferatoractivated receptor delta (PPARD) treatment group (n = 6), which received the same treatment as the chitosan group, followed by intragastric administration of 3 mg/kg GSK0660 (Selleck, Houston, TX, USA, S5817) for 28 days. Cell culture and drug treatments The human epithelial cell line Caco-2 was obtained from and identified by Kunming Institute of Zoology (Strok No. KCB200710YJ). The Caco-2 cell has been extensively used as a specialized model of intestinal epithelial cells in vitro, and accordingly, we selected it to investigate the role of acetate. The cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (Gibco, Suzhou, China, C11995500BT) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco), and incubated under standard cell culture conditions (37°C, 5% CO2). When the cells reached approximately 60%–70% confluency, they were treated with 500 μM sodium acetate, 20 μM of the PPARD agonist GW0742 (Selleck, S8020), 500 μM sodium acetate + 20 μM GW0742, 2 mM of the adenosine 5′-monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) agonist AICAR (MCE, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA, HY-13417), or 500 μM sodium acetate + 2 mM AICAR. The Caco-2 cells were cultured for another 24 hours after drug treatment (Figure 1B) Chitosan has neuroprotective effects in Drosophila melanogaster and PD cell models (Bhattamisra et al., 2020; Pramod Kumar and Harish Prashanth, 2020; Nehal et al., 2021; Sardoiwala et al., 2021); however, the mechanism by which chitosan exerts its neuroprotective effects in PD has not been elucidated, because it is indigestible in vivo (Gallaher et al., 2000; Yao and Chiang, 2006). As shown in Figure 1C, the average body weight was significantly lower in MPTP group than in the control group (P < 0.0001). By contrast, the average body weight in the chitosan treatment group was higher than that in the PD model group. Notably, mice exposed to MPTP exhibited motor dysfunction, while those that received oral administration of chitosan exhibited fewer symptoms (Figure 1D). DA neuron loss in the SN is the primary pathological characteristic of PD. TH is the rate-limiting enzyme in DA synthesis and a specific marker of DA neurons (Roy, 2017). We found that TH protein levels were significantly lower in MPTP-induced PD mice than in control mice (P < 0.0001); however, TH protein levels were partly restored in the chitosan treatment group (P = 0.0042; Figure 1E). Similarly, compared with the control group, there were fewer TH-positive cells in the SN in the MPTP model group; however, the animals treated with chitosan showed increased TH-positive cells by immunofluorescence staining (Figure 1F). The death of DA neurons is accompanied by changes in the levels of DA and its primary metabolites, including 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid (DOPAC) and homovanillic acid (HVA), in the striatum (Yao et al., 2020). The DA content in the striatum of MPTP-induced PD mice was significantly lower than in control mice (P = 0.0002), and the DA content in the chitosan group was significantly higher than that in MPTP-induced PD mice (P = 0.0046; Figure 1G). Nevertheless, there was no significant difference in HVA and DOPAC levels among the three groups. The elevated DOPAC level and HVA/DA ratio in the striatum might be a compensatory mechanism for reduced DA neuron numbers and DA levels, as observed in patients with PD and in PD models (Pifl and Hornykiewicz, 2006). We calculated the DOPAC/DA, HVA/DA, and DOPAC + HVA/DA ratios as a proxy for DA utilization or metabolism. Figure 1G shows that the ratios of DOPAC/ DA, HVA/DA, and DOPAC + HVA/DA ratios in MPTP-induced PD mice were significantly greater than those in control mice (DOPAC/DA: P = 0.0125; HVA/ DA: P = 0.0005; DOPAC + HVA/DA: P = 0.0006). Oral administration of chitosan markedly decreased the DOPAC/DA and DOPAC + HVA/DA ratios (Figure 1G). These findings suggest that chitosan prevents motor dysfunction, facilitates DA neuron survival, increases DA content, and slows DA metabolism.

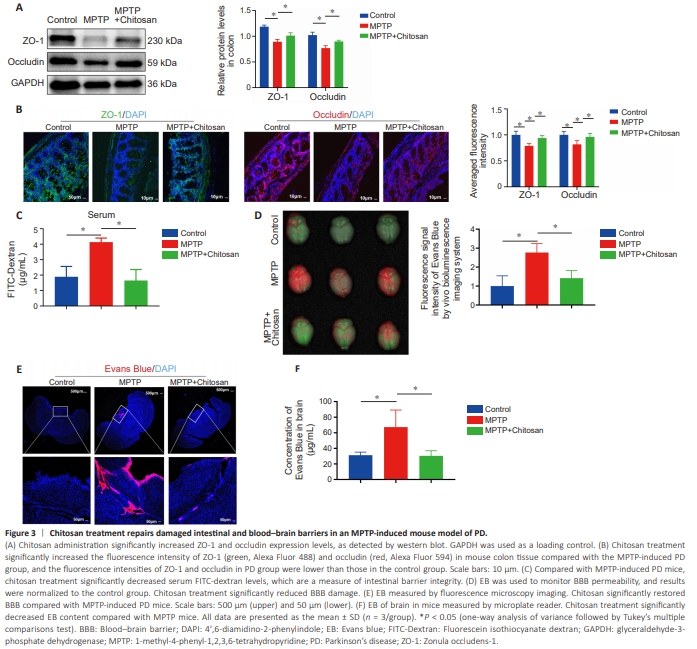

Figure 3 | Chitosan treatment repairs damaged intestinal and blood–brain barriers in an MPTP-induced mouse model of PD.

It is unclear how chitosan alleviates PD symptoms by inhibiting SCFA production in the gut. Recent clinical and laboratory studies have shown that PD disrupts the intestinal barrier (Dong et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2022). Because the primary site of chitosan action after ingestion is the intestine, we first asked whether chitosan alters intestinal function. To test whether chitosan alleviates PD symptoms by repairing the intestinal barrier, we measured the expression levels of the tight junction proteins ZO-1 and occludin, which are necessary for barrier function and integrity (Wu et al., 2000). We found that ZO-1 and occludin were expressed at lower levels in the MPTP group than in the control group, whereas the expression of both proteins was upregulated in the chitosan treatment group (Figure 3A). The ZO-1 and occludin fluorescence intensity results were confirmed by western blotting (Figure 3B). Next, FITC-dextran was used to evaluate intestinal barrier permeability. Under normal conditions, FITC-dextran cannot cross the epithelial barrier. When the intestinal barrier is disrupted due to inflammation, it can be crossed by FITC-dextran (Baxter et al., 2017). A significant increase in FITC-dextran in the serum of MPTP-induced PD mice was observed relative to the control group (P = 0.0078); however, treatment with chitosan decreased serum FITC-dextran levels compared with the MPTP group, suggesting that MPTP-induced PD mice have high intestinal permeability (Figure 3C).Next, we asked whether damage to the intestinal barrier would lead to BBB damage. Evans blue is widely used to evaluate BBB integrity (Xu et al., 2019). The MPTP-induced PD mice exhibited significantly increased BBB leakage compared with control mice (P = 0.0089), and treatment with chitosan reduced BBB leakage (Figure 3D). BBB leakage was also measured in brain sections by fluorescence microscopy, which showed that the Evans blue fluorescence intensity was significantly higher in the MPTP group than in the control group, and that treatment with chitosan significantly reversed this effect (Figure 3E). Next, we confirmed these results by soaking brain tissue in formamide, which is a solvent for Evans blue (Lima et al., 2023), and calculating the brain content of Evans blue based on a standard curve. Consistent with the microscopy results, the formamide quantification results showed that the Evans blue level was significantly elevated (P = 0.0384) in the brains of MPTP-induced PD mice compared with the control mice and decreased following chitosan administration compared with MPTP mice (P = 0.0351; Figure 3F). These results suggest that chitosan may restore damage to the intestinal barrier and the BBB, thereby exerting a therapeutic effect in MPTP-induced PD mice.

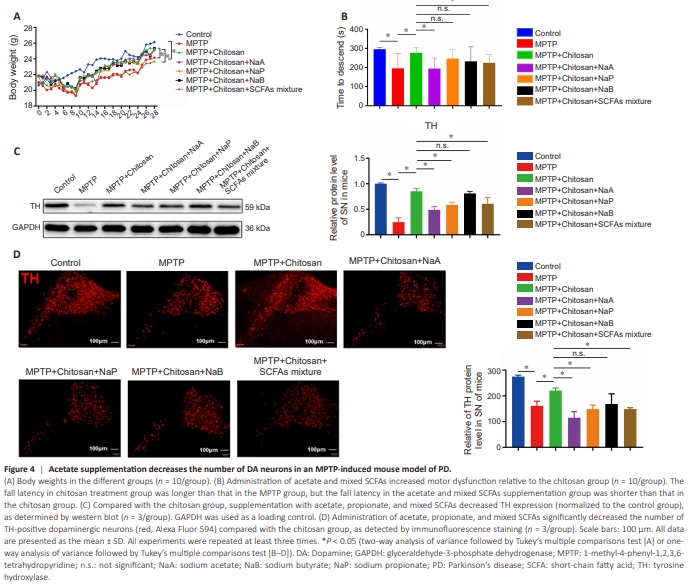

Figure 4 | Acetate supplementation decreases the number of DA neurons in an MPTP-induced mouse model of PD.

To confirm that chitosan alleviates PD symptoms by decreasing SCFA levels, we supplemented the animals’ drinking water with 67.5 mM NaA, 25 mM NaP, 40 mM NaB, and mixed SCFAs (Smith et al., 2013). As shown in Figure 4A, the body weights of the PD mice were significantly lower than those of the control animals (P < 0.0001), while chitosan treatment was associated with weight gain (P < 0.0001). Meanwhile, the mice consuming mixed SCFAs exhibited significantly lower weights than the MPTP + chitosan mice (P < 0.0001; Figure 4A). The MPTP-induced PD mice also demonstrated a significant decrease in fall latency in the rotarod test compared with the control group, while mice treated with chitosan showed improved motor performance (Figure 4B). Compared with the MPTP + chitosan group, the mice that received acetate and mixed SCFAs exhibited significant motor impairment (Figure 4B). Next, we assessed whether SCFAs would reduce the damage to DA neurons, by western blotting and immunofluorescence. Compared with the model group, the chitosan treatment group exhibited higher TH levels. In contrast, acetate, propionate, and mixed SCFAs lowered TH protein levels to PD model levels (Figure 4C). Acetate (P = 0.0003), propionate (P = 0.0093), and mixed SCFAs (P = 0.0093) significantly accelerated DA neuron (TH-positive cell) loss (Figure 4D). These findings suggest that NaA, NaP, and mixed SCFAs reversed the protective effect of chitosan. We also investigated whether acetate would have a negative effect on control and PD model mice. Brain section analysis showed no difference in the number of TH-positive neurons in the SN between control mice with or without NaA, indicating that NaA did notaffect control mice (Additional Figure 2A–C). Similarly, the number of THpositive cells in the MPTP group exposed to NaA decreased compared with the MPTP group, but the difference was not significant. We speculate that this is because the loss of DA neurons induced by MPTP was so severe that any additional DA neuron loss caused by NaA was not evident. In addition, hematoxylin-eosin staining showed that colon tissue in the control + NaA group was structurally intact and contained few infiltrating inflammatory cells, and there was no difference between the control group and the control + NaA group (Additional Figure 2D). The QPCR analysis results were consistent with the hematoxylin-eosin staining results, in that the relative mRNA levels of IL-1β and IL-6 in the colon tissue of control + NaA mice were comparable to those seen in the control mice (Additional Figure 2E). Therefore, we explored acetate further in subsequent experiments, as it appeared to cause motor impairment and DA neuron loss.

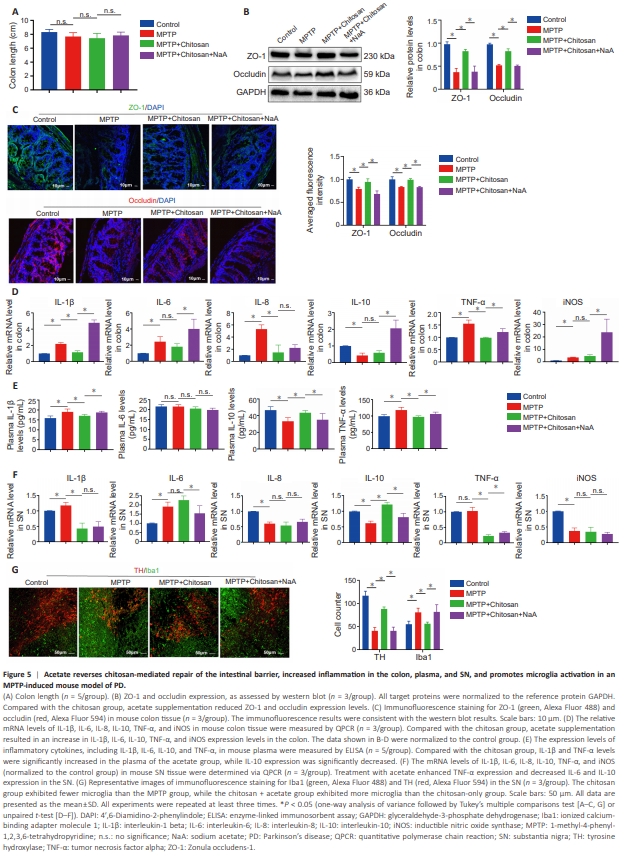

Figure 5 | Acetate reverses chitosan-mediated repair of the intestinal barrier, increased inflammation in the colon, plasma, and SN, and promotes microglia activation in an MPTP-induced mouse model of PD.

SCFAs interact locally with intestinal epithelial cells to mediate intestinal mucosal immunity and barrier function (Dalile et al., 2019). As described above, we found that chitosan treatment restored intestinal barrier integrity (Figure 4). Colon length is a marker for evaluating the severity of colonic inflammation (Tanaka et al., 2003). We observed no significant difference in colon length among the groups including the control, MPTP, chitosan and chitosan + NaA groups (Figure 5A). ZO-1 and occludin protein levels were elevated in the chitosan group than MPTP group; however, acetate supplementation was associated with a decreasing trend in the expression of these two proteins (Figure 5B). Likewise, immunofluorescence analysis of colon sections showed that ZO-1 and occludin expression levels were lower in the acetate group than in the chitosan group (Figure 5C). These findings suggest that acetate suppresses ZO-1 and occludin expression, thereby damaging the mouse intestinal barrier. It remains unclear how disruption of the intestinal barrier aggravates PD. Talley et al. (2021) reported that local inflammation in the colon drives systemic inflammation and neuroinflammation through the gut–brain signaling axis, potentially mediated by the gut microbiota; alternatively, inflammation in the intestine could lead to systemic inflammation and subsequently activate CNS inflammation. To explore the effect of acetate supplementation on inflammation following chitosan treatment, we measured changes in inflammatory factors in the colon, plasma, and SN. Levels of the pro-inflammatory factors IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, and iNOS were elevated in the colon in MPTP group compared with the control group. The expression level of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 in the colon was lower in MPTP mice than in control mice (Figure 5D). Compared with the MPTP group, mice treated with chitosan showed lower IL-1β, IL-8, and TNF-α expression levels in the colon, but no significant changes in IL-6, IL-10, or iNOS expression levels (Figure 5D). However, acetate supplementation increased IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and iNOS expression in the colon (Figure 5D). SCFAs affect systemic inflammation by regulating interleukin secretion (Dalile et al., 2019). Mice in the MPTP group exhibited higher plasma IL-1β and TNF-α levels than control mice (Figure 5E), while chitosan treatment significantly reduced IL-1β (P = 0.0128) and TNF-α (P = 0.0003) levels and increased IL-10 (P = 0.0002) levelsin mouse plasma compared with the MPTP group (Figure 5E). By contrast, IL1β (P = 0.0014) and TNF-α (P = 0.0095) levels were significantly increased, and plasma IL-10 (P = 0.0162) levels were decreased, by acetate treatment (Figure 5E). There was no difference in plasma IL-6 levels among all groups (Figure 5E). Next, we sought to determine whether increased inflammatory responses occurred in the CNS following acetate administration. We found that IL-1β and IL-6 levels were elevated, while IL-8, IL-10, and iNOS (not TNF-α) levels were reduced, in the SN of mice in the MPTP group compared with control mice (Figure 5F). Chitosan treatment downregulated IL-1β and TNF-α and upregulated IL-10 in the SN compared with the MPTP group (Figure 5F). Acetate supplementation elevated TNF-α expression and reduced IL-6 and IL-10 expression in the SN compared with the chitosan group (Figure 5F). There no significant differences in IL-1β, IL-6, or TNF-α expression levels in cerebrospinal fluid among the groups (Additional Figure 2F). The presence of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the colon, plasma, and SN in MPTP-induced PD mice suggests that systemic inflammation includes neuroinflammation. Microglia are the primary resident innate immune cells of the CNS, and activated microglia secrete pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines that contribute to neuroinflammation (Voet et al., 2019). Immunofluorescence staining for Iba1, a marker of activated microglia, showed that there were more Iba1-positive cells in the SN in the MPTP group than in the control group, and that chitosan treatment induced a marked decrease (Figure 5G). Acetate amplified the number of Iba1-positive cells (Figure 5G). These findings suggest that, in MPTP-induced PD mice treated with chitosan, acetate supplementation inhibits the expression of tight junction proteins, thereby impairing the integrity of the intestinal barrier, increasing systemic inflammation, and ultimately triggering CNS inflammation, especially in the SN.

Figure 8 | Chitosan may reduce acetate levels, thereby activating the PPARD-AMPK signaling pathway, which promotes repair of the intestinal barrier and reduces neuroinflammation in an MPTP-induced mouse model of PD.

Next, we tested whether PPARD and AMPK signaling are involved in the chitosan-mediated inhibition of inflammation via acetate in the MPTPinduced mouse model of PD. p-AMPK and PPARD expression levels in the colon of MPTP-induced PD mice were decreased compared with the control group, and treatment with chitosan eliminated this effect (Figure 8A and B). Supplementation with acetate partially restored p-AMPK and PPARD expression levels (Figure 8A and B). Consistent with the results shown in Figure 7, there was no significant difference in AMPK expression among the four groups (Figure 8A and B). To determine whether chitosan inhibits PPARD or AMPK expression in the SN via acetate, we examined PPARD, p-AMPK, and AMPK expression in the SN. However, no significant differences were observed in the expression levels of these proteins among the control, MPTP, MPTP + chitosan, and MPTP + chitosan + NaA groups (Additional Figure 3A and B). A previous study has shown that PPARD activation has anti-inflammatory effects in neuroinflammation-related diseases (Bishop-Bailey and Bystrom, 2009). Therefore, we asked whether the PPARD antagonist GSK0660 could alleviate the neuroprotective effects of chitosan in the MPTP-induced mouse model of PD. As shown in Figure 8C, mouse body weight decreased significantly following treatment with the PPARD antagonist (P = 0.0010). Next, we examined the effect of the PPARD antagonist on motor deficits and found that it did not significantly alter motor dysfunction (Figure 8D). PPARD expression levels were lower in the group treated with both chitosan and the PPARD antagonist than in the group treated with chitosan only (Figure 8E). In addition, western blot analysis showed that treatment with the PPARD antagonist induced a clear decrease in TH expression (Figure 8F). Treatment with the PPARD antagonist was associated with a significant decrease in ZO-1 and occludin expression in mouse colon tissue (Figure 8G).Consistent with these results, we found that ZO-1 (P = 0.0339) and occludin (P = 0.0228) fluorescence intensities were significantly lower in the presence of the PPARD antagonist compared with the chitosan group (Figure 8H). IL-6 (P = 0.0443) and TNF-α (P = 0.035) mRNA levels were significantly elevated after administration of the PPARD antagonist (Figure 8I). Compared with mice that did not receive the PPARD antagonist, plasma IL-1β (P = 0.0014), IL-6 (P = 0.0069), and TNF-α (P < 0.0001) levels were significantly elevated in the PPARD antagonist group (Figure 8J). IL-1β (P = 0.0001), IL-6 (P = 0.0326), and IL-8 (P = 0.0452) levels were significantly higher in mice exposed to the PPARD antagonist than mice that were not exposed to the PPARD antagonist (Figure 8K). The findings suggest that the PPARD antagonist aggravates inflammation in the colon, plasma, and SN. Interestingly, p-AMPK expression in the colon was significantly reduced in mice treated with the PPARD antagonist compared with the chitosan group (P = 0.0349), but AMPK expression levels did not change (Figure 8L). This finding suggests that the PPARD antagonist significantly increased DA neuron death in the SN and aggravated inflammation in the colon, plasma, and SN in an MPTP-induced mouse model of PD. Taken together, our data suggest that PPARD/AMPK signaling suppresses neuroinflammation caused by chitosan reducing acetate in PD.