神经退行性病

-

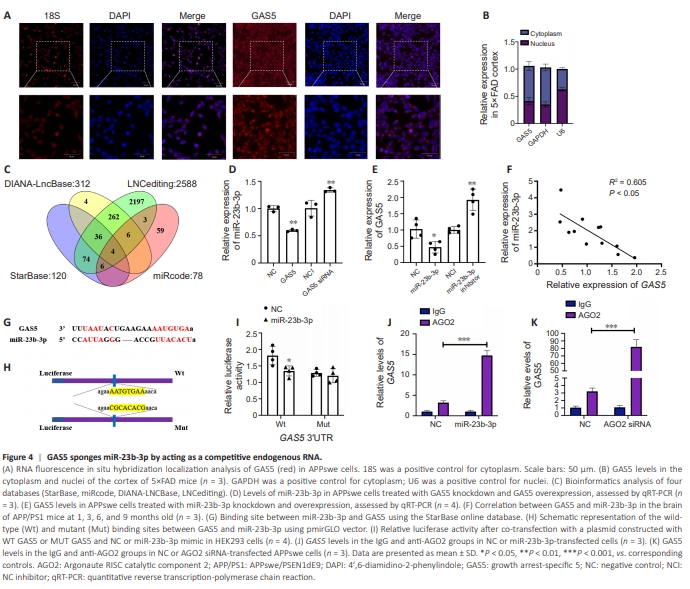

Figure 4 | GAS5 sponges miR-23b-3p by acting as a competitive endogenous RNA.

Before exploring GAS5 pathogenesis in AD, the distribution of GAS5 within different subcellular regions was examined. FISH experiments showed that GAS5 shuttled between the cytoplasm and nucleus in APPswe cells (Figure 4A), and was primarily localized in the cytoplasm in the cortex of 5×FAD mice (Figure 4B), indicating that GAS5 is a largely cytoplasmic lncRNA. Cytoplasmic lncRNAs have been shown to bind to miRNAs, lose their ability to interact with target mRNAs, and act as ceRNAs or sponges (Cao et al., 2018; Tang et al., 2020). Subsequent bioinformatics analyses of four databases (StarBase, miRcode, DIANA-LncBase, and LNCediting) showed GAS5 binding to four intersected miRNAs (Figure 4C). Of these, miR-23b-3p and miR-1297 showed better species conservation in primates and mammals (Additional Table 2). However, miR-1297 expression was not regulated by GAS5 overexpression or knockdown (Additional Figure 4). In previous studies, we identified that miR23b-3p was dysregulated and suppressed tau phosphorylation via specific binding to GSK-3β 3′-UTR (Jiang et al., 2022). Thus, we assessed the miR-23b3p level, which was significantly decreased when GAS5 was overexpressed (P < 0.01 vs. NC; Figure 4D), and increased when GAS5 was silenced (P < 0.01 vs. NCI; Figure 4D). The GAS5 level was significantly decreased or increased byup- or down-regulating miR-23b-3p, respectively (both P < 0.05 vs. NC/NCI; Figure 4E). Furthermore, miR-23b-3p was negatively correlated with GAS5 expression in APP/PS1 mice (R2 = 0.605, P < 0.05; Figure 4F). The Starbase database indicated putative binding sites of GAS5 and miR-23b3p (Figure 4G). To validate the relationship, a dual-luciferase reporter system was established using a cloning sequence of the binding site or its mutation into a luciferase vector (Figure 4H). miR-23b-3p inhibited luciferase activity in Luc-GAS5-Wt-transfected cells compared with cells co-transfected with NC (P < 0.05 vs. NC; Figure 4I). Furthermore, the GAS5 mutation sequence did not influence luciferase activity, suggesting a direct interaction of GAS5 with miR23b-3p. AGO2 serves as a critical regulator of miRNA silencing function, and therefore an anti-AGO2 RIP assay was performed. Endogenous GAS5 pull-down by AGO2 was significantly increased in miR-23b-3p-transfected APPswe cells (P < 0.001 vs. NC; Figure 4J). In contrast, AGO2 silencing attenuated AGO2- dependent degradation of GAS5 and increased the GAS5 level (P < 0.001 vs. NC; Figure 4K), implying that miR-23b-3p bound to GAS5 and mediated its degradation. These results support that GAS5 directly targeted miR-23b-3p and regulated its expression.

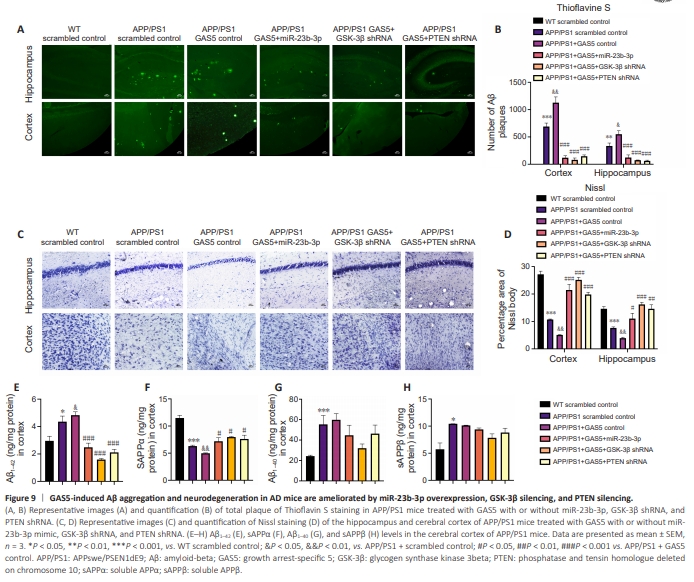

Figure 9 | GAS5-induced Aβ aggregation and neurodegeneration in AD mice are ameliorated by miR-23b-3p overexpression, GSK-3β silencing, and PTEN silencing.

To elucidate the ceRNA role of GAS5 in vivo, the transfection efficiencies of miR-23b-3p, GSK-3β shRNA and PTEN shRNA in APP/PS1 mice were verified by qRT-PCR (Additional Figure 7A–C). GAS5 was overexpressed with or without miR-23b-3p, GSK-3β shRNA, and PTEN shRNA via intracerebroventricular injection with AAV vectors into APP/PS1 mice (Additional Figure 7D). GAS5 overexpression exacerbated cognitive impairment in APP/PS1 mice (all measures P < 0.05 vs. APP/PS1 + scrambled control; Figure 8A, C, and D). Notably, administration of miR-23b-3p mimic, GSK-3β shRNA, and PTEN shRNA to APP/PS1 mice significantly ameliorated the learning and hippocampus-dependent memory deficits induced by GAS5 (all measures P < 0.05 vs. APP/PS1 + GAS5 control; Figure 8A, C, and D), and these mice had more precise and well-defined travel paths in the MWM test (Figure 8E). Swimming speeds were indistinguishable (Figure 8B), indicating that the GAS5/miR-23b-3p/GSK-3β/PTEN axis had little effect on motivation. The histopathological assay results indicated that the GAS5-induced increases of Aβ deposition, characterized by Thioflavin S (ThS) staining, and neuronal loss, indicated by Nissl staining, in the APP/PS1 mice (all P < 0.05 vs. APP/ PS1 + scrambled control; Figure 9A–D) were significantly reversed after cotreatment with miR-23b-3p mimic, GSK-3β shRNA, and PTEN shRNA (all P < 0.05 vs. APP/PS1 + GAS5 control; Figure 9A–D). Subsequent ELISA showed that GAS5 increased the Aβ1–42 level and decreased the sAPPα level (both P < 0.05 vs. APP/PS1 + scrambled control; Figure 9E and F), and did not affect the levels of Aβ1–40 and sAPPβ (Figure 9G and H), whereas miR-23b-3p mimic, GSK-3β shRNA, and PTEN shRNA had the opposite effects on Aβ1–42 and sAPPα in the cortex of APP/PS1 mice (all P < 0.05 vs. APP/PS1 + GAS5 control; Figure 9E and F). Therefore, these results suggest a potential role of GAS5in the miR-23b-3p/PTEN/GSK-3β axis involved in spatial cognition, neuronal degeneration, and amyloid load in vivo.