神经退行性病

-

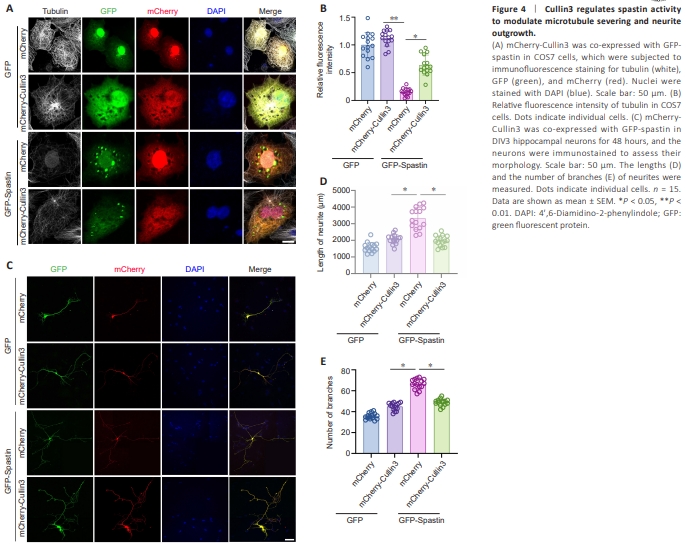

Figure 4 | Cullin3 regulates spastin activity to modulate microtubule severing and neurite outgrowth.

Next, we asked whether Cullin3-mediated degradation affects spastin function. GFP-spastin was overexpressed with or without mCherry-Cullin3 in COS7 cells, which have a flattened cell morphology conducive to analyzing the structure of the microtubule cytoskeleton. Immunocytochemistry assay showed that overexpression of mCherry-Cullin3 alone did not induce microtubule severing (Figure 4A, line 2), while overexpression of GFP-spastin resulted in spastin clustering and significant microtubule severing (Figure 4A, line 3). However, Cullin3 overexpression markedly suppressed spastin clustering and inhibited spastin-induced microtubule severing (Figure 4A, line 4). Statistical analysis of the microtubule fluorescence observed in the affected cells is shown in Figure 4B. Furthermore, mCherry-Cullin3 overexpression did not affect neurite outgrowth in cultured hippocampal neurons (Figure 4C). GFP-spastin overexpression increased neurite length and branch number, and this effect was suppressed by mCherry-Cullin3 overexpression (Figure 4C–E). These findings suggest that Cullin-3–induced degradation inhibits the spastinmediated microtubule severing and promotion of neurite outgrowth.

Figure 5 | RBX1 is the E2 ligase component involved in spastin ubiquitination.

CRLs comprise a Cullin scaffold protein, small RING proteins (RBX1 or RBX2), adapter proteins, and substrate recognition proteins and RBX proteins, and serve as E2 ligases (Zhang et al., 2024). To determine which RING protein is involved in spastin ubiquitination, we constructed plasmids encoding Flag-RBX1 and Flag-RBX2. Flag-RBX1, but not Flag-RBX2, overexpression decreased GFP-spastin levels in HEK293 cells (Figure 5A). Indeed, Flag-RBX1 overexpression induced spastin degradation in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5B). Furthermore, co-immunoprecipitation revealed that RBX1 was pulled down with spastin (Figure 5C). Overexpression of RBX1 or Cullin3 alone resulted in spastin degradation, and co-overexpression of the two proteinsenhanced this destabilizing effect (Figure 5D). Flag-RBX1 overexpression in COS7 cells did not induce microtubule severing, but did mitigate the loss of microtubule mass induced by GFP-spastin overexpression (Figure 5E and F). Furthermore, Flag-RBX1 overexpression in hippocampal neurons did not affect neuronal length or the number of branches; however, it did attenuate the promotion of neurite outgrowth induced by GFP-spastin overexpression (Figure 5G–I). Our proteomics analysis also identified several potential BTB subtypes (data not shown), all of which require further validation. Taken together, these findings indicate that RBX1 serves as a crucial component of the E2 ligase complex, playing a pivotal role in regulating spastin protein stability and activity.

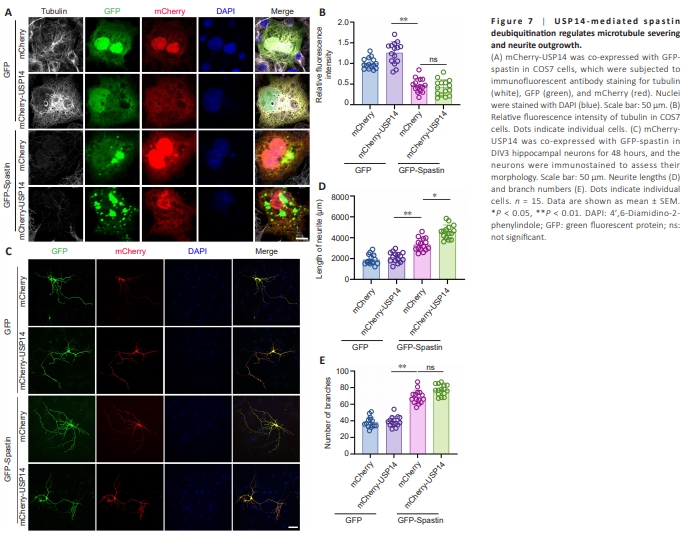

Figure 7 | U S P 1 4 - m e d i a t e d s p a s t i n deubiquitination regulates microtubule severing and neurite outgrowth.

As depicted in Figure 7A, USP14 overexpression alone increased cytoskeletal mass and the number of spastin puncta. However, USP14 overexpression did not enhance microtubule severing compared with spastin overexpression, as shown in Figure 7B. This may be because microtubule severing was already sufficiently activated by spastin alone. Regarding neurite outgrowth, USP14 overexpression alone did not demonstrate any impact on the length or number of branches (Figure 7C). However, overexpression of both USP14 and spastin further enhanced the length, though not the number, of branches, in hippocampal neurons (Figure 7D and E).

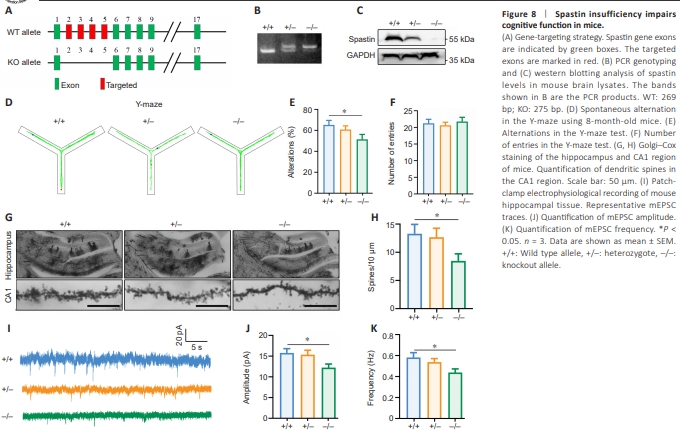

Figure 8 | Spastin insufficiency impairs cognitive function in mice.

To determine the impact of spastin insufficiency in vivo, we generated spastin knockout mice using the CRISPR-Cas9 system, targeting exons 2–5 (Figure 8A). Global depletion of spastin gene expression was confirmed by quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction and western blotting (Figure 8B and C). Given our focus on hippocampal neurite outgrowth, we decided to evaluate memory function in +/+, +/–, and –/– mice using the Y-maze test. As depicted in Figure 8D–F, spastin loss led to decreased spontaneous alternations among the maze arms compared with the control wild-type (+/+) mice, although there was no difference in the number of entries among the genotypes (Figure 8F). As shown in Figure 8G, although spastin knockout did not result in an overall loss of hippocampal mass, spine density in the CA1 region was significantly reduced in ?/? mice (Figure 8G and H). Moreover, when cultured hippocampal neurons were subjected to cell patch-clamp analysis to assess signal transduction, we found that spastin-depleted cells exhibited significantly decreased amplitude and frequency of AMPAR currents in response to spontaneous miniature excitatory postsynaptic current (mEPSC) stimulation (Figure 8I–K). Taken together, these findings indicate that spastin insufficiency in vivo alters hippocampal structure and impairs neuronal signal transmission.