周围神经损伤

-

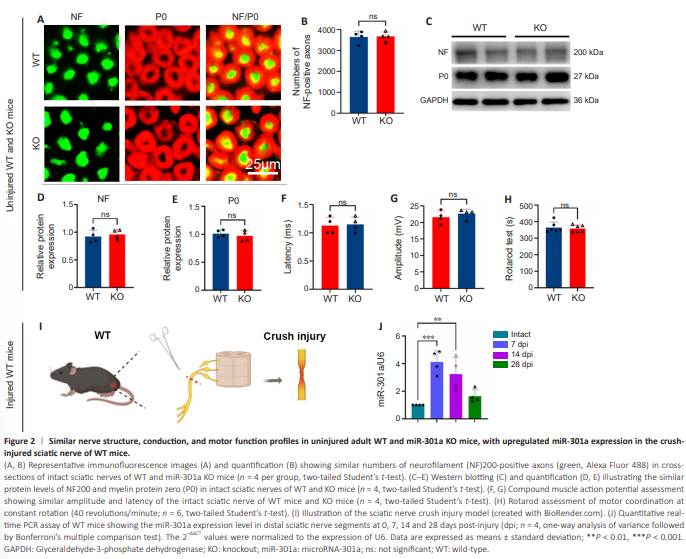

Figure 2 | Similar nerve structure, conduction, and motor function profiles in uninjured adult WT and miR-301a KO mice, with upregulated miR-301a expression in the crushinjured sciatic nerve of WT mice.

Considering our plan to utilize miR-301a-KO mice to explore the role of this miR in nerve regeneration, we sought to first investigate the potential effect of miR-301a KO on morphological and functional profiles of mice prior to nerve injury surgery. Immunofluorescence staining revealed that the densities of neurofilament (NF)200-positive axons and protein zero (P0)-positive myelin in intact sciatic nerves were not markedly different between the KO and WT groups (Figure 2A and B). Western blotting also showed similar levels of NF200 and P0 total protein between the two groups (Figure 2C– E). In addition, the compound muscle action potential (Figure 2F and G) and rotarod assessment (Figure 2H) indicated that the miR-301a KO did not affect nerve conduction or motor function in intact WT and KO mice. Furthermore, qRT-PCR analysis of miR-301a in WT mice showed low expression in the intact nerve, followed by marked upregulation at 7 days following sciatic nerve crush injury and a gradual decline thereafter (Figure 2I and J).

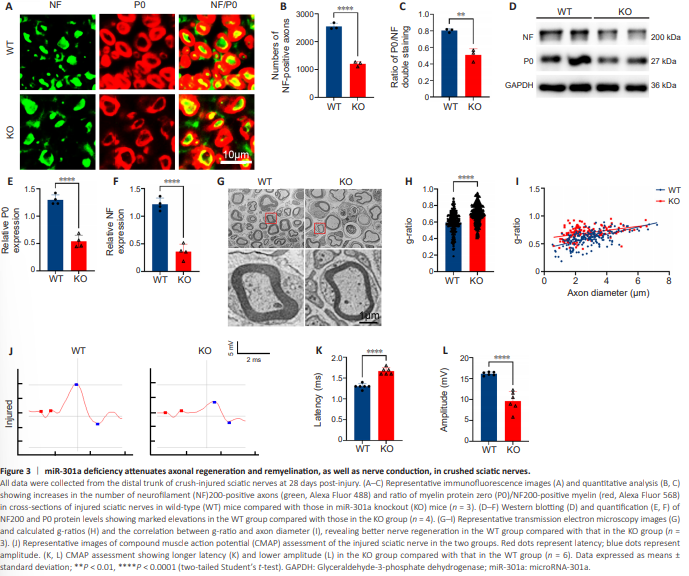

Figure 3 | miR-301a deficiency attenuates axonal regeneration and remyelination, as well as nerve conduction, in crushed sciatic nerves.

In view of the dramatic upregulation of miR-301a in the injured nerve, which suggested that it may be involved in the regulation of nerve injury response and repair, we examined the structural and functional repair at 28 dpi in mice with sciatic nerve crush injury. Immunofluorescence in the KO group revealed a significantly lower density of NF200-positive axons in the distal trunk of the injured nerve, and a markedly reduced percentage of P0/NF200 doublepositive nerve fibers in all NF200 single-positive axons, compared with the WT group (Figure 3A–C). Collectively, these findings suggested that miR-301a depletion attenuates axonal regeneration and remyelination in the injured nerve. This view was supported by the results of western blotting (Figure 3D–F) and transmission electron microscopy (Figure 3G). Specifically, g-ratio analysis based on transmission electron microscopy images suggested that the myelin of regenerated nerve fibers was significantly thinner in the KO group than in the WT group (Figure 3H and I). The link between conduction function and the structural repair of injured nerves is well established. Therefore, we conducted an electrophysiological assessment of compound muscle action potential of the injured nerve (Figure 3J), which showed lower amplitude and increased latency in the KO group compared with that in the WT group (Figure 3K and L).

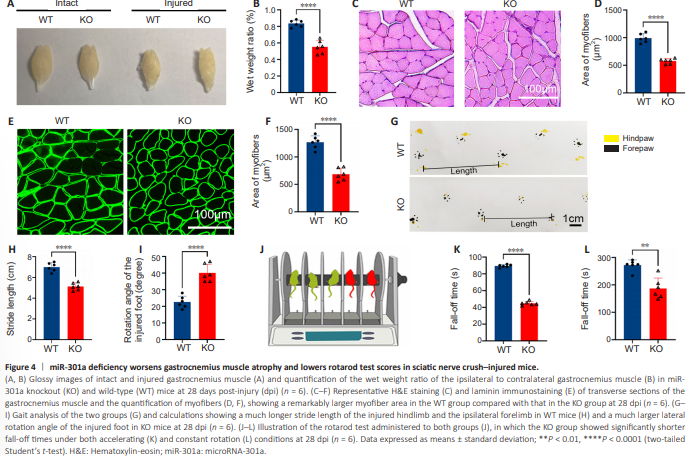

Figure 4 | miR-301a deficiency worsens gastrocnemius muscle atrophy and lowers rotarod test scores in sciatic nerve crush–injured mice.

One of the main consequences of nerve injury – myoatrophy in the target muscles – can be reversed to some extent by axonal regeneration and reinnervation of the target muscles. Motor function is also restored to a certain level (Li et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2021). We found that the wet weight ratio of the ipsilateral to the contralateral gastrocnemius muscle was dramatically lower in the KO group than in the WT group (Figure 4A and B). Furthermore, the myofiber size, as determined by hematoxylin-eosin staining (Figure 4C and D) and laminin immunofluorescence (Figure 4E and F), was significantly reduced in the KO group compared with that WT group. Consistently, the gait test demonstrated that KO of miR-301a shortened the stride length and increased the lateral rotation angle of the nerve injury– affected foot (Figure 4G–I), while the rotarod test showed that miR-301aKO mice had a shorter fall-down time compared with WT mice (Figure 4J– L). Together, these findings indicated that miR-301a depletion weakens functional repair following sciatic nerve injury.

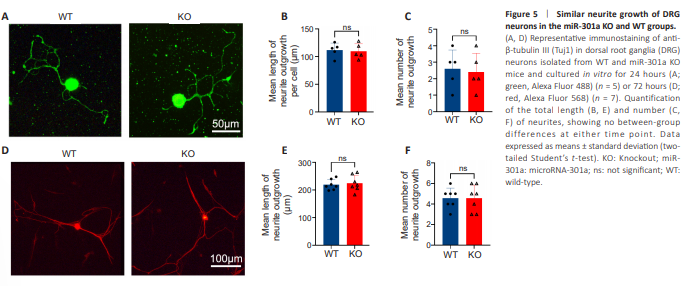

Figure 5 | Similar neurite growth of DRG neurons in the miR-301a KO and WT groups.

To clarify whether the above outcomes were related to the involvement of miR-301a in the neurite regeneration ability of neurons, we cultured DRG neurons isolated from WT and KO mice. There were no statistical differences between the WT and KO group neurons in terms of the number of processes or total length of all processes of each neuron following 24 hours (Figure 5A–C) or 72 hours (Figure 5D–F) of culture in vitro.

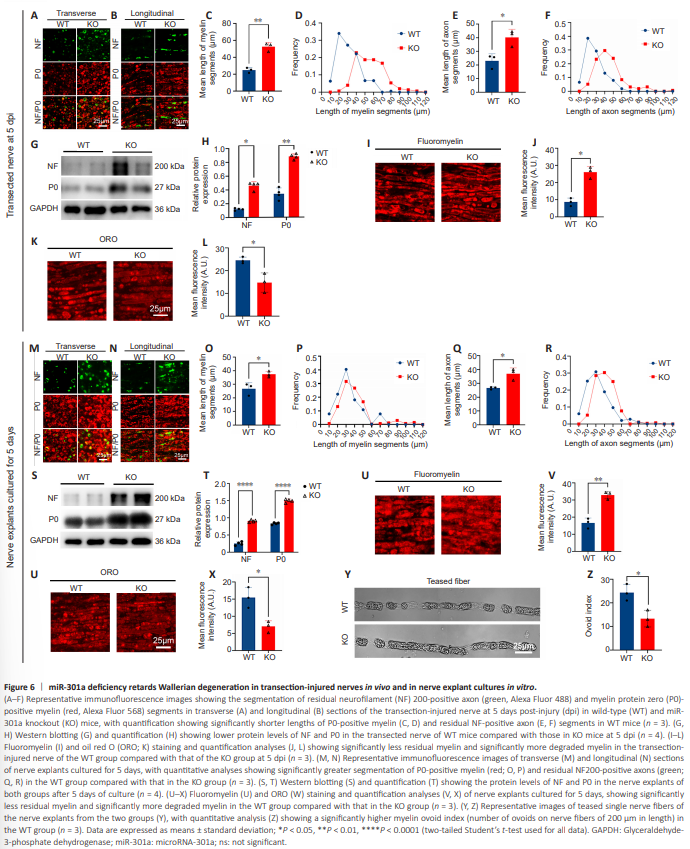

Figure 6 | miR-301a deficiency retards Wallerian degeneration in transection-injured nerves in vivo and in nerve explant cultures in vitro.

Having shown that KO of miR-301a did not impact the neurite growth of DRG neurons, we hypothesized that the absence of miR-301a in the local microenvironment of the injured nerve might contribute to a delay in nerve regeneration. WD is a main event in the early stages of nerve injury, and is also a prerequisite for creating an environment favorable to nerve regeneration (Yuan et al., 2022). Recently, we reported that miR-301a deficiency weakens the migration and phagocytosis of macrophages (Xu et al., 2022), which led us to hypothesize that miR-301a KO might affect WD. To test this hypothesis in an in vivo model with minimal interruption of nerve regeneration, we assessed WD in terms of residual axon and myelin using mice with sciatic nerve transection. Transverse sections (Figure 6A) and longitudinal sections (Figure 6B) of the transected nerve at 5 dpi showed that the remaining P0-positive myelin segments (Figure 6C and D) and NF200-positive axonal segments (Figure 6E and F) were significantly longer in the KO group than in the WT group. The pattern of NF200 and P0 protein levels revealed by western blotting was similar to that under immunostaining (Figure 6G and H). Furthermore, the intensity of fluoromyelin-labeled residual myelin was higher in the KO group (Figure 6I and J), while the intensity of ORO staining of degraded myelin was weaker in the KO group (Figure 6K and L), compared with those in the WT group. Notably, similar results were observed in a nerve explant model after 5 days of culture in vitro (Figure 6M–X). Moreover, there were far fewer myelin ovoids in teased single nerve fibers from the KO group than in those from the WT group (Figure 6Y and Z). Overall, these data pointed to a mechanism of delayed WD in miR-301a KO mice.

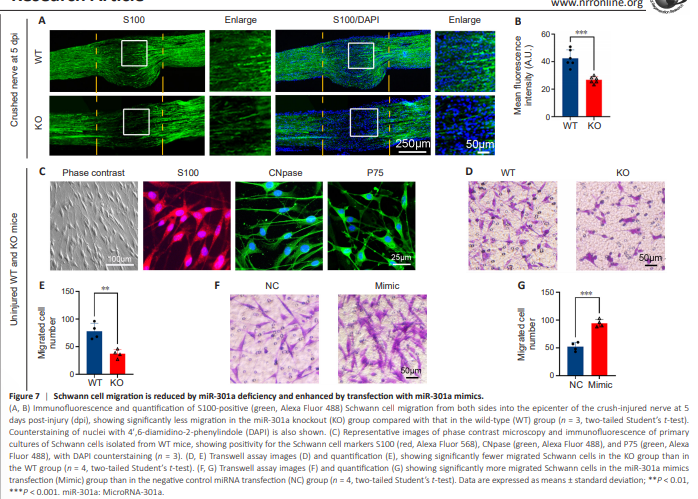

Figure 7 | Schwann cell migration is reduced by miR-301a deficiency and enhanced by transfection with miR-301a mimics.

Based on a previous study of Schwann cell activities during peripheral nerve regeneration (Shen et al. 2022), we evaluated Schwann cell migration in WT and miR-301a-KO mice using S100 immunostaining of longitudinal sections of crush-injured sciatic nerves at 5 dpi. Our data indicated that miR-301a deficiency reduced migration of Schwann cells from the two sides into the injured area (Figure 7A and B). To elucidate this phenomenon, we evaluated the migration of isolated, positively identified Schwann cells (Figure 7C) using a Transwell culture system. The results showed that compared with the WT group, a significantly smaller number of cells in the KO group migrated across the Transwell membrane over 20 hours of culture (Figure 7D and E). Conversely, primary cultures of WT mouse-derived Schwann cells that were transfected with miR-301a mimics exhibited a significant increase in the number of migrated cells compared with those transfected with NC miRNA (Figure 7F and G).

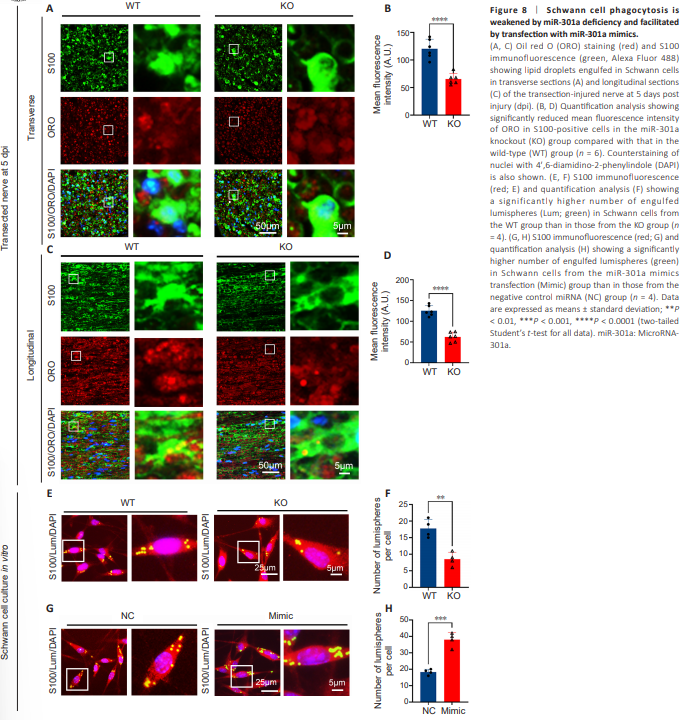

Figure 8 | Schwann cell phagocytosis is weakened by miR-301a deficiency and facilitated by transfection with miR-301a mimics.

Based on previous studies in macrophages (Xu et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2023), we performed S100 immunofluorescence and ORO staining of transectioninjured nerve sections at 5 dpi, and then calculated the ORO-positive fluorescence intensity in each Schwann cell. Quantification analyses of both transverse sections (Figure 8A and B) and longitudinal sections (Figure 8C and D) showed that the Schwann cells in the KO group engulfed significantly fewer ORO-positive lipids than those in the WT group. Additionally, the co-culture of Schwann cells with fluorescent microspheres illustrated that cells in the KO group phagocytosed significantly fewer microspheres than those in the WT group (Figure 8E and F). In contrast, miR-301a mimics-transfected Schwann cells derived from WT mice phagocytosed more fluorescent microspheres than NC-transfected cells (Figure 8G and H). These results confirmed that miR-301a plays vital roles in the migratory and phagocytic capabilities of Schwann cells.

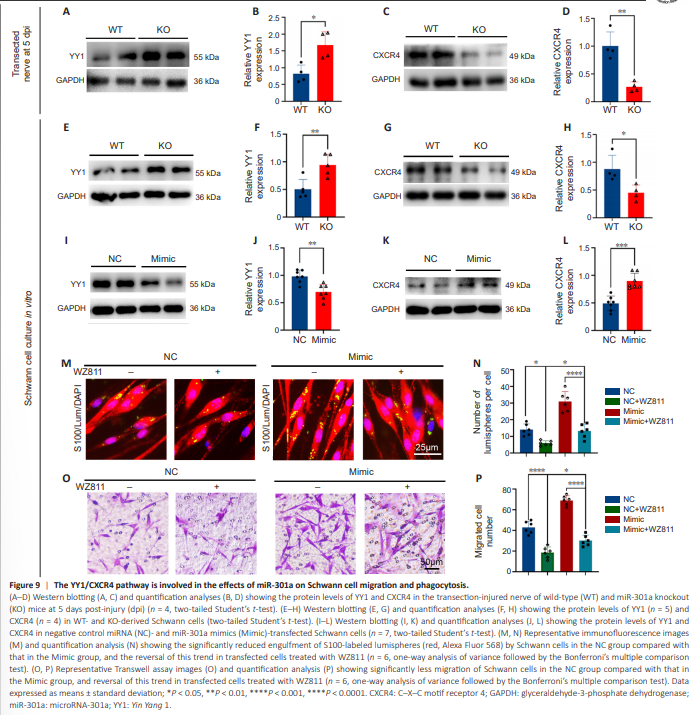

Figure 9 | The YY1/CXCR4 pathway is involved in the effects of miR-301a on Schwann cell migration and phagocytosis.

To determine whether miR-301a exerts its effects on Schwann cell functioning through the Yin Yang-1 (YY1)/CXCR4 pathway, we examined the expression levels of YY1 and CXCR4 in transection-injured nerves and cultured Schwann cells from miR-301a KO and WT mice. Western blotting results indicated that the miR-301a KO increased YY1 expression (Figure 9A and B) and downregulated CXCR4 expression (Figure 9C and D) in transection-injured nerves at 5 dpi. These changes were also observed in vitro in cultured Schwann cells isolated from miR-301a-KO mice and WT mice (Figure 9E–H). To confirm these results, we transfected the cultured Schwann cells derived from WT mice with miR-301a mimics, which resulted in downregulation of YY1 (Figure 9I and J) and increased expression of CXCR4 (Figure 9K and L). Furthermore, treatment of the transfected Schwann cells with the CXCR4- specific inhibitor WZ811 remarkably reversed the effects of miR-301a mimics on phagocytosis, as indexed by lumisphere engulfment (Figure 9M and N), and migration, as revealed by the Transwell assay (Figure 9O and P). These results indicated that miR-301a impacts Schwann cell functioning through the YY1/CXCR4 pathway.